On May 25, 1968, surgeons in Richmond, Virginia, were successful hert transplant, one of the first in the world, on a white businessman. The heart they used was taken from a Black patient named Bruce Tucker who was taken to the hospital the day before, unconscious and with a fractured skull and traumatic brain injury. He was pronounced brain dead less than 24 hours later.

Tucker’s still beating heart was then removed without the knowledge of his family or prior permission; her horrific discovery – by the local funeral director – that Tucker’s heart was missing was a devastating blow.

The actions of the surgeons, which led to America’s first civil case for wrongful death, are revealed in the new book. “The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South“(Simon and Schuster, 2020) by Pulitzer Prize-nominated journalist Charles” Chip “Jones. Jones raises troubled questions about the ethics of this pioneering work, revealing his deep roots in racism and discrimination against Black people in health care.

Related: 7 Reasons America Still Needs Civil Rights Movements

The first human organ transplant, a kidney, took place in 1954, and in the late 1960s ‘superstar’ surgeons were on their way to being the first to successfully transplant a human heart, Jones told Live Science.

“As far as science is concerned, it was the medical parallel to the space race,” Jones said.

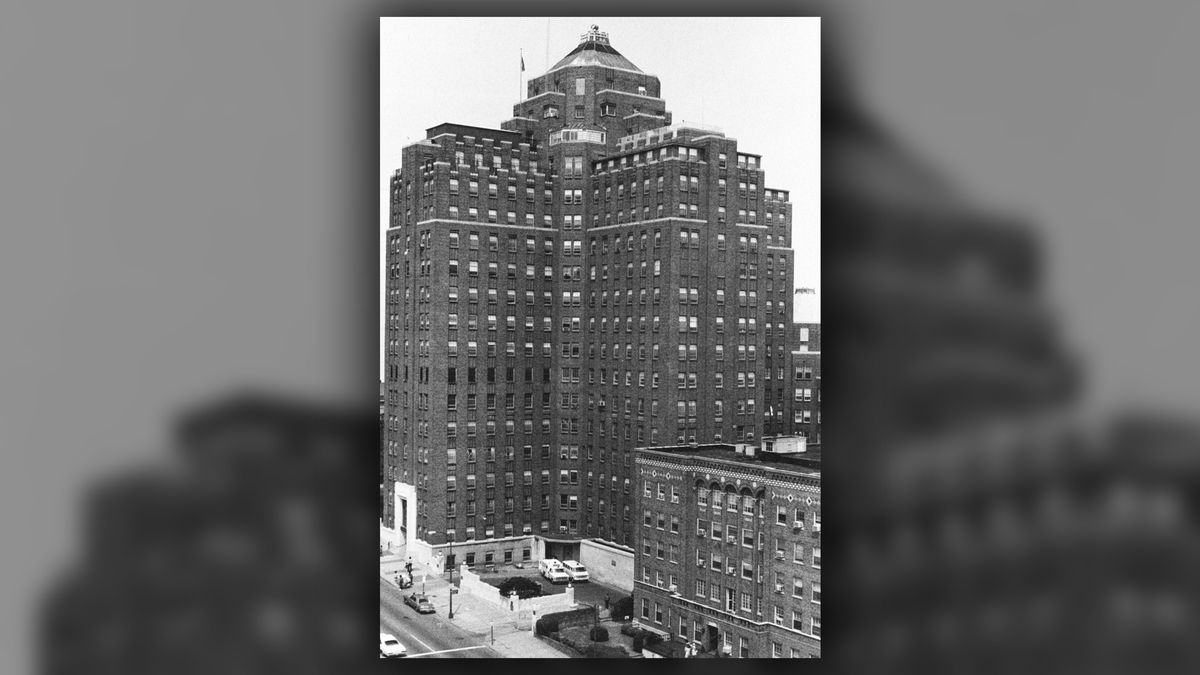

Dr. Richard Lower and Dr. David Hume, surgeons at the Medical College of Virginia (MCV) in Richmond, was at the forefront of that race, but it was South African surgeon Dr Christiaan Barnard who performed the first heart transplant on Dec. 3, 1967. In May of 1968, MCV admitted a pregnant patient to his hospital coronary heart disease who was a doctoral candidate for a heart transplant. But Lower and Hume still had to find a viable heart donor.

And with time for their sick patient out, they needed one quick.

The “benevolent patient”

Tucker, a Richmond factory worker who had sustained a serious head injury in a fall, was taken to MCV Hospital on May 24, 1968. Although Tucker’s personal effects included one of his brother’s business cards, officials could not name a family member on behalf of the unconscious man. And because the hospital claimed Tucker had no family and had alcohol on his breath (he drank prior to his accident), he was profiled as a “benevolent patient” and marked as a potential heart donor.

“He was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Jones said.

Tucker was connected to a ventilator, unable to breathe. A junior medical researcher performed an electroencephalogram (EEG) to determine electrical activity in Tucker’s the brain; the examiner explained that there was none. The surgeons pronounced this as sufficient evidence of brain death; Tucker was taken out of the vent, and Hume and Lower removed Tucker’s heart for the transplant, Jones wrote.

Related: What happens to your body when you are an organ donor?

Decades later, in 1981, the Uniform Determination of Death Act provided a legal definition of death: “irreversible cessation of circulatory and pulmonary functions” and “irreversible cessation of all functions of the cerebrum,” meaning that the cerebrum – including the brainstem – ceases to function, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

But in 1968, the legal concept of death was not so clearly defined, Jones said.

“There was no statutory framework that would let doctors know how to proceed in a situation like this, where they had a patient who they legally thought had no chance of recovering,” Jones explained. “And time was of the essence to save a very sick man.” However, doctors were also quick to assume that Tucker was indifferent and without family – a racially motivated judgment, according to Jones.

Related: The 9 most interesting transplants

The Tucker family learned that his heart was missing from the funeral director; they put together what had happened from news reports (Tucker’s identity was not initially released to the public, Jones wrote). Eventually, the Tucker family would file a civil lawsuit for wrongful death, which went to trial in 1972. Representing her was attorney L. Douglas Wilder, who later became the first elected black governor in the U.S.

According to Wilder, Lower said “intentionally, wrongly, willfully and intentionally killed Bruce O. Tucker prior to his actual death, in violation of the law, knowing that he was not legally qualified to do so.” State lights required family report and waited 24 hours for operation to be performed.

“She skipped the process that was in place in Virginia because she was so eager to finally do the surgery,” Jones said.

The famous case of Henrietta Lacks presents a similar clash between medical ethics and racism. Lacks, a Black woman (also from Virginia), was diagnosed in 1951 with cervical cancer. A doctor collected cells from one of her tumors and then reproduced them indefinitely in the lab; after Lacks’ death, those cells were then scattered among scientists for years without the knowledge or permission of their family. Known as the HeLa cell line, they were used in research that led to cancer treatments and the discovery of the polio vaccine, but decades passed before Lacks’ family learned of their medical “immortality.”

In 2013, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reached an agreement with the family to allow future research using data from HeLa cells; the new process requires application through a panel that includes descendants and relatives of Lacks, Live Science previously reported.

“The body man”

The injustice experienced by Lacks, Tucker and their families stems from racism that is deeply embedded in America’s medical infrastructure, Jones noted. In fact, when medical colleges in America adopted a more practical approach to anatomical studies in the 19th century, instructors often trained their students in human anatomy using the carcasses of Black people stolen from African-American cemeteries, wrote Jones.

Robbery was technically illegal, but when Black people were the victims, authorities were on the other side, according to Jones. Medical schools would hire a “bodybuilder” (also called a “resurrectionist”) to procure bodies; at MCV, the designated grave robber was a Black man named Chris Baker, a janitor at the school who lived in the basement of the high school’s Egyptian building.

Most of the country’s medical schools abandoned this racist method of obtaining corpses by the mid-1800s, but records suggest it continued in Virginia until at least 1900, Jones said.

“There were reports of bodies being ‘snatched’ from the state of Virginia’s pen, which is about five blocks from the medical college,” he said.

Jones unexpectedly discovered a memory of this crime when he examined his book, in a mural displayed at MCV’s McGlothlin Medical Education Center. Painted between 1937 and 1947 by Richmond artist George Murrill, and carries the painting from the medical college. And it includes the image of a corpse being forcibly removed from a grave in a wheelbarrow.

“It shows how the legacy of racism literally lies right under people’s noses,” Jones said.

“The organ thieves” is on sale on 18 Aug. read an excerpt here .

Originally published on Live Science.