Ganymede is Jupiter's largest moon and the ninth largest object in our solar system. This moon is even bigger than the planet Mercury. The last time we had good close-up images was of the Galileo mission to Jupiter in the late 1990s. Those images provided a detailed look at much of Ganymede's surface, but Galileo never managed to capture Jupiter's north pole. Now, thanks to NASA's Juno spacecraft currently orbiting Jupiter, we have the first images of the north pole of this large Jovian moon.

Unlike the Galileo mission, Juno is not specifically designed to study Jupiter's moons. Juno's images are not as high-resolution as Galileo's in the 1990s, in part because they were taken from farther away. And Juno's images show the infrared view, which shows the amount of heat radiated by Ganymede at various points near its pole, rather than visible light images that reveal what our eyes would see.

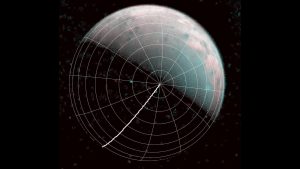

Still, the images give an insight into this part of Ganymede that has never been seen before. The JIRAM instrument on the Juno spacecraft, also known as the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper, acquired the images as part of the spacecraft's mapping of the moon's northern regions. JIRAM used high-contrast imaging and spectroscopy to study Jupiter's polar regions during Jupiter's flyby on December 26, 2019. At the time, Ganymede was in sight of Juno. The spacecraft was programmed to rotate its instruments towards Ganymede during this time.

On the closest approach to Ganymede, about 62,000 miles (100,000 km), JIRAM collected 300 infrared images of the moon's surface, with a spatial resolution of 14 miles (23 km) per pixel.

Now ... what do the new images show?

Multiple infrared views of Ganymede's north pole, captured by the Juno spacecraft on December 26, 2019. Image via NASA / JPL-Caltech / SwRI / ASI / INAF / JIRAM.

We already knew that, like many moons in the outer solar system, Ganymede is primarily made up of water ice. It is believed to have an ocean of water beneath an outer ice crust.

A significant finding from these new Juno images is that the ice at the north pole of Ganymede is not immaculate. Plasma has acted on it from Jupiter's colossal magnetosphere, which is about 20,000 times stronger than Earth's magnetosphere. Ganymede has only an extremely thin atmosphere, so Jupiter's plasma can reach the surface without hindrance, greatly affecting the surface of the ice. Alessandro Mura, Juno co-researcher at the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome, commented:

JIRAM data shows that the ice at and around the north pole of Ganymede has been modified by plasma precipitation. It is a phenomenon that we were able to learn for the first time with Juno because we can see the North Pole in its entirety.

Researchers can also see that the ice near northern Ganymede and the south poles have a different infrared signature than the ice at the Ganymede equator. This polar ice is amorphous, that is, it lacks a definite shape or form. The amorphous is because Ganymede is the only moon in the solar system with its own magnetic field. The charged particles follow the lines of the moon's magnetic field to the poles, where they impact and wreak havoc on the ice, preventing it from having an ordered (or crystalline) structure.

Scientists have discovered that even frozen water molecules in these regions have no order in their arrangement.

Juno's new data shows how he can contribute to the study of Jupiter's moons, even though his primary mission is to study Jupiter. According to Giuseppe Sindoni, program manager of the JIRAM instrument for the Italian Space Agency:

These data are another example of the great science that Juno is able to observe when looking at Jupiter's moons.

Ganymede, seen in color enhanced by the Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. Image via NASA / Phys.org.

Another natural color view of Ganymede from Galileo in the late 1990s. Image via NASA.

Artistic concept of auroras in Ganymede. This is made possible by the fact that Ganymede is the only known moon that has a magnetic field. Image via NASA / ESA.

Cross section of the interior of Ganymede showing an ocean of water below the surface. Image via NASA / ESA / A. Feild (STScI) / Space.com.

JIRAM's main task is to observe infrared light coming from Jupiter's deep atmosphere. It can probe up to 30 to 45 miles (50 to 70 km) under Jupiter's clouds. But, along with Ganymede, the instrument can also be used to study the Io, Europa, and Callisto moons. Those four moons are known as the Galilean moons, named after the astronomer Galileo who discovered them in 1610. They are Jupiter's four largest moons.

Thanks to its magnetic field, Ganymede also has auroras, like Earth, despite the fact that its atmosphere is extremely dim and almost non-existent. The Ganymede Ocean is estimated to be 60 miles (100 km) thick, 10 times deeper than Earth's oceans, and is buried under a 95-mile (150 km) crust of mostly ice.

With a diameter of 3,273 miles (5,268 km), it is 26% larger than the planet Mercury in volume, although it is only 45% larger. Ganymede has an iron core, a rocky mantle surrounded by a blanket of ice, an oceanic ocean surrounding the mantles, and an ice crust on top.

Giuseppe Sindoni, program manager of the JIRAM instrument for the Italian Space Agency. Image via ResearchGate.

Juno can see Ganymede only from a distance, but the European Space Agency (ESA) JUpiter ICy Moons Explorer (JUICE), slated for launch in 2022, will study Ganymede, Callisto and Europe in detail after it reaches Jupiter in 2029. This will make it the first mission to do so from Galileo.

For now, Juno has provided at least a glimpse of Ganymede's north pole for scientists to study. In the not too distant future, missions like JUICE will reveal much more about this tempting world.

Read more about NASA's Juno mission.

Bottom line: NASA's Juno spacecraft has taken the first images of Ganymede's north pole.

Via Jet Propulsion Laboratory