As befits the man he commemorated, John Lewis’s Thursday funeral in Atlanta was a public symphony, a rhetorical masterpiece of pride, praise, and calls to continue the work of the great man.

Three former presidents spoke, all with emotional admiration for the 80-year-old civil rights leader and longtime Democratic congressman from the 5th District of Georgia, who died on July 17.

Barack Obama delivered the heartfelt and heartfelt keynote, calling on Americans to pay their respects to Lewis as he continues his work at a time when black lives and voting rights remain at risk, but Bill Clinton and George W Bush spoke with the same force. and well of a man who always put truth before politics.

Like Lewis Sheila Lewis O’Brien’s niece, Rev. Dr. Bernice King, activist Xernona Clayton, Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi, Rev. Dr. Raphael G. Warnock, senior pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church where the funeral was held, and the others who spoke

For a country confined by a pandemic and, more importantly, a culture increasingly dependent on often unreliable social media platforms for the exchange of information, ideas, ideas and calls to action, it was like a sustained rain in the midst of a drought: a reminder of the unique and necessary art of the spoken word.

Lewis certainly understood the power of public eloquence; At the age of 15, he heard Martin Luther King Jr. speak on the radio and that changed his life.

Detained 45 times for more than half a century past fighting for civil rights and beaten unconscious in 1965 on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, where he and 600 peaceful protesters marched toward the vicious batons of Alabama state soldiers, Lewis was very a man of action and words.

But from his opening speech before the 1963 March in Washington to a recent Zoom meeting in which he and former President Barack Obama spoke with a group of activists, Lewis was so master of the microphone that when his final essay appeared in The New York Times on Thursday. , we could hear his voice as we read.

Quiet, calm, and utterly unforgiving, Lewis was a tireless and democratic speaker, as comfortable on late-night and morning talk shows as he was in Congress or at any VIP table. He said what he thought: he believed, for example, that Russian interference in the 2016 election made Donald Trump’s presidency illegitimate, and backed him up with action: He did not attend Trump’s inauguration. (That’s why Trump did not speak at Lewis’s funeral or earlier this week, when Lewis became the first black lawmaker to lie in the state at the United States Capitol Rotunda.)

Obviously, no one is going to praise and bury John Lewis without preparing the best possible speech.

That type of preparation: the elaboration of the tone and the phrase, of pause and crescendo; The correspondence of the message with the music has fallen out of favor recently. The emergence of the personal narrative at the end of the millennium as a valid and necessary social force gave us a new vernacular: “authenticity”, which often values the uncomfortable and imprecise about the polished, the raw and emotional about the carefully discussed or poetically borrowed.

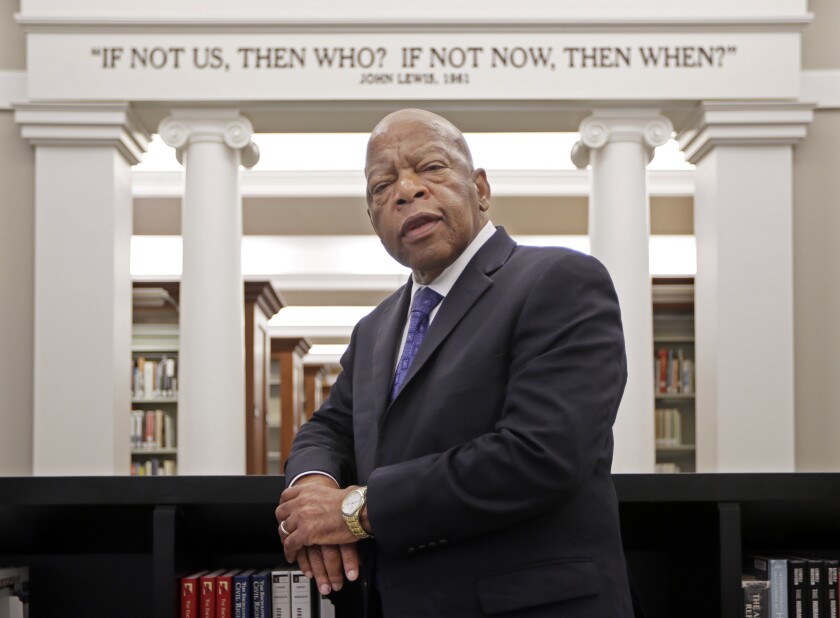

Representative John Lewis, who died on July 17 at 80.

(Mark Humphrey / Associated Press)

Since then, social media has become the preferred form of social discourse, and with a trust in immediacy, brevity, and niche marketing, much of this is not designed for complex phrases.

Do not misunderstand. The validation of personal narratives is one of the greatest cultural revolutions of all time. The definition of what makes something good or valid, beautiful or important has been controlled by a few, including those considered great public speakers. By relaxing the standards of public speaking, like social media, millions of years have kept quiet the opportunity to speak without fear of being looked down on by non-sequencing.

Unfortunately, our demand for “authenticity” has been accompanied by a rejection of what is carefully considered. Rhetoric, which actually means the art of speaking or writing effectively, is considered elitist by some, synonymous with obfuscation or falsehood by others. Consistent messages are often dismissed as “talking points” (as if repetition implied a lack of sincerity), and, as Hillary Clinton discovered, a ready response or speech is often criticized for appearing “over-thought” or “rehearsed “

Like almost everything else, prayer has long been judged by traditions and preconceptions: women’s voices, naturally sharper, kept many of them off the lists of great public speakers, and the preference for round vowels eliminates people whose accents don’t match. It is a talent, like the ability to deliver great performance, and like any performative talent, it requires experience to perfect itself. Lewis, as former President Bush recalled Thursday, began his public speaking career preaching to his chickens.

Still, if you think any of the great speeches in history was not “over-thought” and somehow rehearsed, you are missing the point. Practice is the mother of authenticity.

Lewis spoke often about the preparedness that allowed him and his fellow activists to endure the threats and violence they experienced, the rigor that allowed them to overcome natural reactions of fear and anger.

Yes, there are people, born with natural eloquence, who can pronounce makeshift words to make you cry or burn you and make the world better right now.

But looking at the powerful, loving, and rhetorically expert speeches made in honor of John Lewis, it was impossible not to also see the time, attention, and thought that went into them. Were they meticulously crafted and possibly rehearsed? Yes. Were they authentic? Absolutely.

During his eulogy, Bill Clinton reported asking Lewis about how close he was to being killed while protesting. Lewis described a time when, after being shot down during a demonstration, he saw a man lifting a heavy pipe clearly aimed at Lewis’s head. At the last minute, Lewis turned and the crowd moved forward, separating the man from him; Lewis considered himself lucky to be alive.

Clinton, however, thought that Lewis survived for reasons other than luck. “First, because he was a quick thinker. And second, because I was here on a mission that was greater than personal ambition.

“Things like that sometimes just happen,” Clinton said, “but they usually don’t happen.”