Tokyo – Under pressure from the scientific community, the World Health Organization recognized last week that airborne transmission of “droplets” as a possible third cause of COVID-19 infections. For many researchers in Japan, admission felt anticlimactic.

This densely populated country has operated for months on the assumption that small “aerosolized” particles in crowded environments are turbulently loading the spread of the new coronavirus.

Very few diseases (tuberculosis, chickenpox, and measles) have been considered communicable through aerosols. Most are spread only through direct contact with infected people or their body fluids, or contaminated surfaces.

Still, the WHO has declined to confirm aerosols as a major source of new coronavirus infections, saying more evidence is needed. But scientists keep pushing.

“If the WHO recognizes what we did in Japan, perhaps in other parts of the world, it will change (its antiviral procedures),” said Shin-Ichi Tanabe, a professor in the architecture department at Japan’s prestigious Waseda University. He was one of the 239 internationals. scientists who co-wrote an open letter to WHO urging the United Nations agency to review its guidelines on how to stop the spread of the virus.

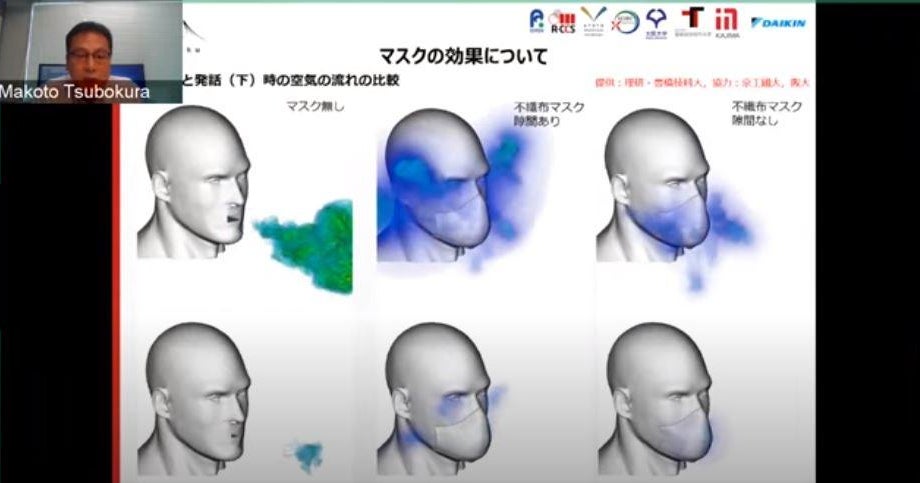

Large droplets ejected from the nose and mouth tend to fall quickly to the ground, explained Makoto Tsubokura, who runs the computational fluid dynamics laboratory at Kobe University. For these larger respiratory particles, social distancing and face masks are considered adequate safeguards. But in rooms with dry and stale air, Tsubokura said his research showed that people who cough, sneeze, and even talk and sing, emit small, gravity-defying particles capable of staying in the air for many hours or even days, and travel along. of a room

The key defense against aerosols, Tsubokura said, is to dilute the amount of virus in the air by opening windows and doors and ensuring that HVAC systems circulate fresh air. In open-plan offices, he said the partitions should be high enough to avoid direct contact with large droplets, but low enough to avoid creating a virus-laden air cloud (55 inches or head height). It can also help spread viral density in the air.

For the Japanese, the latest WHO admission at least vindicated a strategy the country adopted in February, when residents were told to avoid “the three Cs”: confined spaces, crowded areas, and close conversation.

DISTRIBUTE

After a pause, new infections, mainly among Tokyo’s youngest residents, have recently re-emerged, surpassing 200 for four days in a row, before dropping back to 119 on Monday.

It is alarming that new cases emerge not only in notoriously crowded and crowded nightlife venues, but also within homes and workplaces, prompting the national government to consider asking companies to close again in the greater metropolitan region. . Authorities are eager to avoid a corresponding increase in serious cases and deaths, which, so far, have remained low.

Tsubokura, who also serves as principal investigator for the RIKEN government institute, has directed simulations on Japan’s new Fugaku supercomputer studying how to protect yourself against airborne transmission within the subway, offices, schools, hospitals and other public spaces.

RIKEN

Your passenger computer model on the congested Tokyo Yamanote train line (watch the animation at 7:15 minutes in this video) illustrated how air flow stagnates in full trains with closed windows, in contrast to free flowing air in cars with few passengers and open windows. He suggests keeping windows open at all times to mitigate risks when trains fill up.

But Japan’s infamously congested trains, he argues, are probably not as risky as his model suggests. “It is very full and the air is bad,” said Kurokabe. “But nobody talks and everyone is wearing a mask. The risk is not that high.”

Even riding a crowded subway train, if the windows are kept open, as they are in Japan these days, “is much safer than a pub, restaurant or gym,” said Tanabe of Waseda University.

Masking the nose and mouth is even more important, he said, because his research shows that men touch their faces up to 40 times an hour. (He said that women, more likely to wear makeup, are less sensitive to the face.)

“Non-woven (surgical) masks are high performance, but fabric works, too, it’s much better than nothing,” he said. “The only way to prevent (droplet) leakage is by adjusting the mask well.”

RIKEN

Mask and ventilation guidelines are helping the Japanese reopen concert halls, baseball stadiums, and other places. As of last Friday, such venues can accommodate up to 5,000 customers.

Tanabe will rely on Japan’s new Fugaku supercomputer, recently declared the fastest in the world, to map the optimal efficiency of the ventilation system.

“It is like predicting a typhoon,” he said, noting that forecasting extreme weather and air flow through crowded trains depends on the same equations to calculate fluid dynamics.

Environment International / Science Direct

In an article to be published in the September issue of the scientific journal. International environment – As schools and other public facilities struggle to reopen – Tanabe and other experts argue that protecting interior spaces can be done relatively simply and inexpensively, by avoiding overcrowding and keeping air flow fresh.

.