[ad_1]

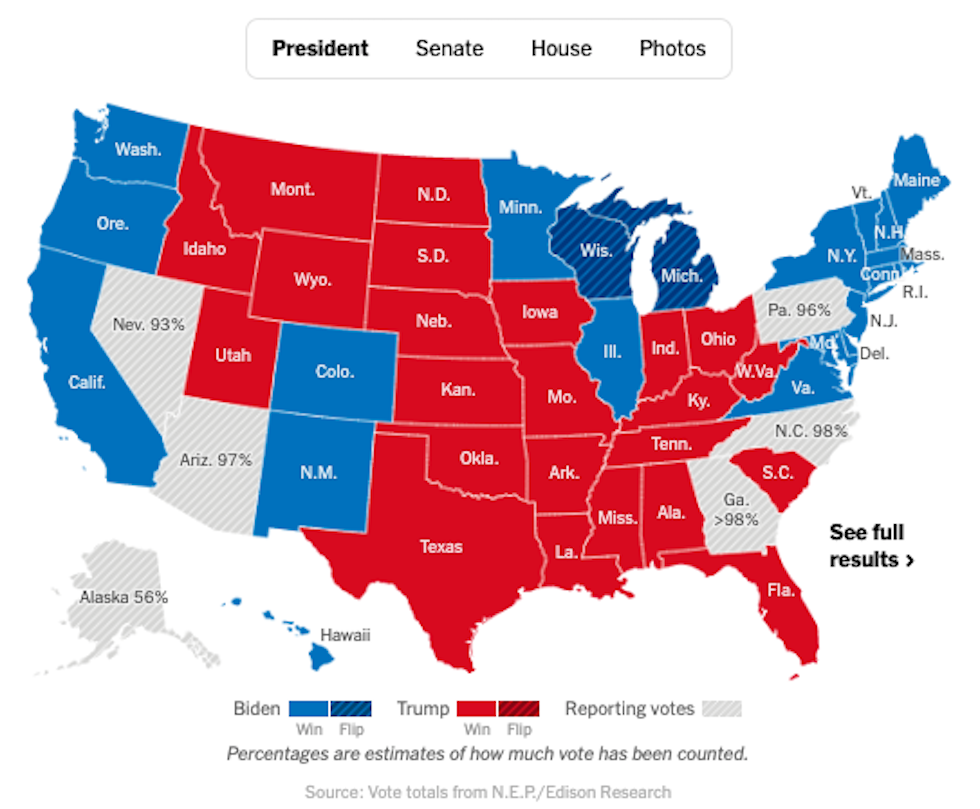

In the early hours of the US presidential elections, which are still ongoing today, an electoral map was released very different from the one we are used to seeing. For about thirty years, the vast majority of maps used by newspapers, books and televisions show a huge red expanse in the central area, indicating the states where Republicans have obtained the most votes, while the blue of the Democrats dot some areas. peripherals and colors a part of the coasts. The impression, in short, is that the vast majority of the country votes for the Republicans while the Democrats are limited to the coasts, and in any case they are more marginal.

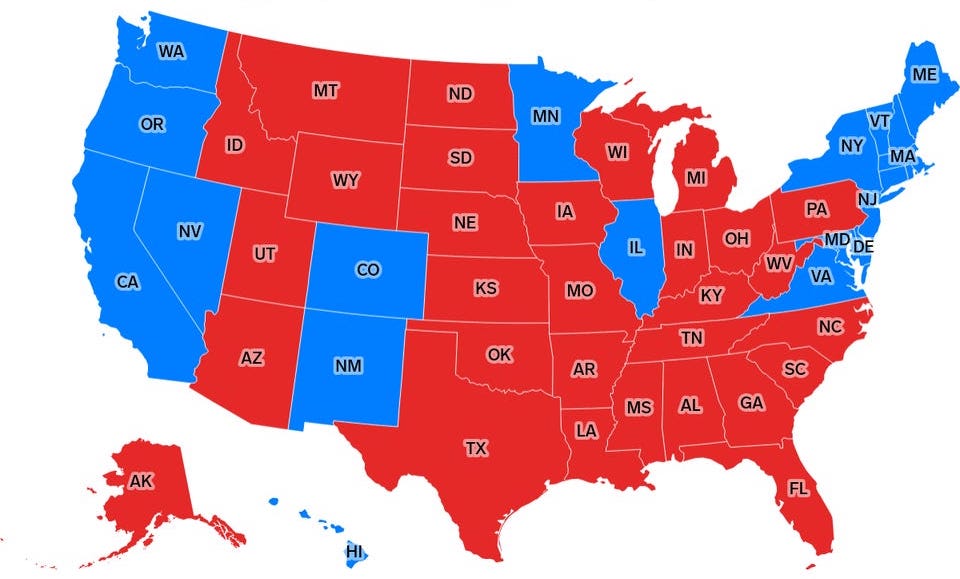

The electoral map of the final results of the 2016 presidential elections: in red the states that voted for Donald Trump, in blue those won by Hillary Clinton

Although such a view is justified above all by US electoral law, according to which the candidate who wins even one more vote in a state gets all of its “big voters,” who then elect the president, the distortions of such a map are evident. First, they tend to overestimate the Republican consensus, given that unless there are striking election results, the electoral map will always be a little redder than blue: the largest states are in fact also those where rural areas are concentrated. , traditionally very conservative. (We also know that our brain perceives objects colored in intense tones such as red as being larger.)

But the ability of a state to influence presidential elections does not depend on its area, but on the population: that is why Massachusetts, where almost seven million people live, has 11 important voters, while Montana, where it lives around one million. people, only 3. However, on the electoral map that we are used to seeing, Montana – which has a huge area, larger than Germany’s – is much more visible than Massachusetts, so small that on some maps it is practically invisible .

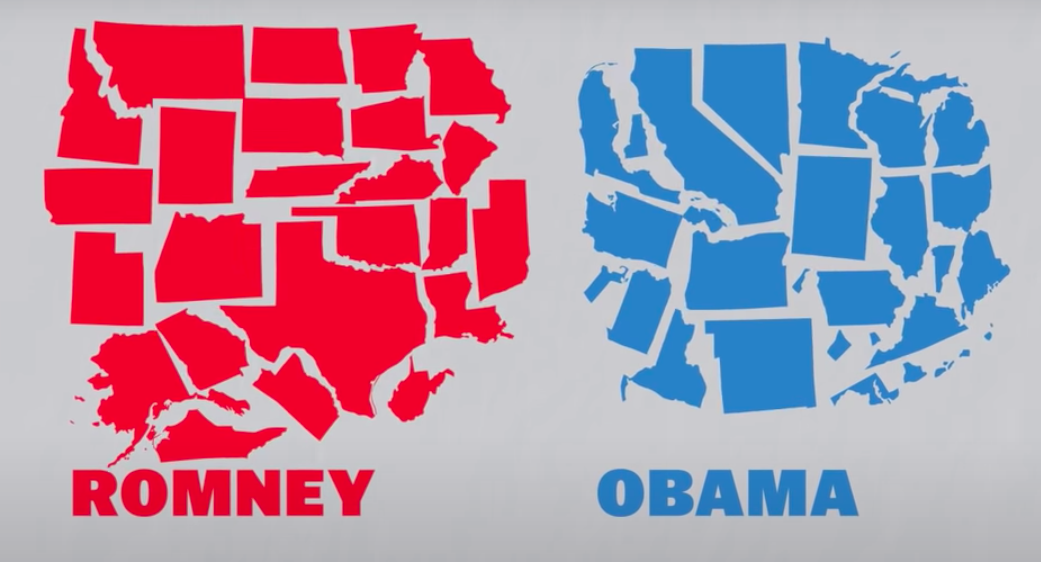

Election map of the 2012 presidential election, overwhelmed by Obama, broken down by Vox: Montana is the first state in the upper left of those won by Romney, Massachusetts is the smallest visible state in the left side of the states won by Obama (Vox)

Another obvious flaw is that such maps are unable to represent the nuances of consensus obtained by a candidate. In the 2016 electoral maps, for example, Michigan is tinted red because Trump won it: but what the map does not say is that the margin between him and Clinton was about 9 thousand votes out of 5 million, and that some years Michigan it is a tendingly democratic state, so much so that in 2020 it was won again by Biden.

Ultimately, the main problem is that when using this map “we have chosen to give priority to geographical precision over electoral importance,” he summarized. Vox: “Geographically accurate maps are fine for a car trip, but they don’t tell us how the country voted.”

No map can be perfect, and even the most harmless ones contain gods. bias, that is, deviations from a totally neutral representation (that is why, for example, the maps we use in the West show Europe at the center of the world). For some years now, someone has tried to introduce solutions to remedy the well-known distortions of the most common electoral maps, with interesting but still not entirely satisfactory results.

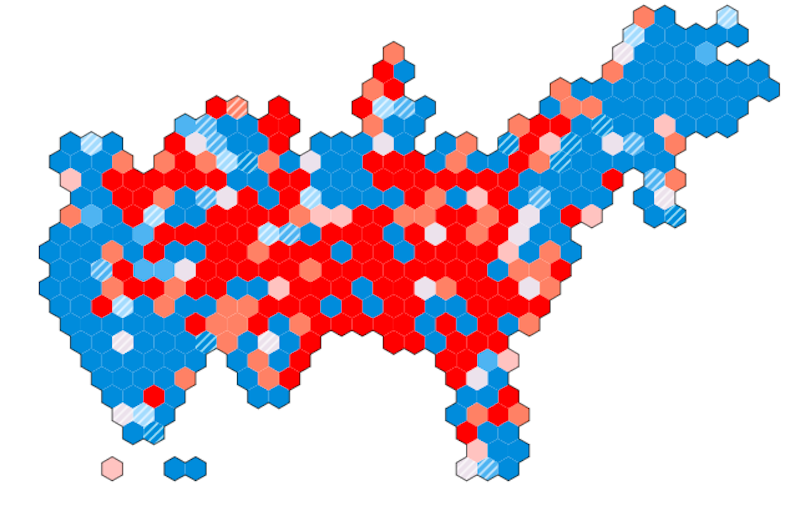

To balance the second problem we were talking about, namely the superficial representation of the consensus, maps were introduced showing the votes obtained by the candidates at the local, provincial or constituency level: as in this graph of the Washington Post, which also uses different shades depending on the percentage of votes obtained by the two candidates. However, even solutions of this kind do not seem to solve the problem, on the contrary: since rural areas include counties and districts much larger than urban and peripheral ones, red areas seem even more prevalent than the state-by-state map (in an election in which Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, however, garnered nearly three million more votes than Trump).

(Washington Post map showing who got the most votes among Democrats and Republicans in 2016 at the national, state, county, and constituency levels)

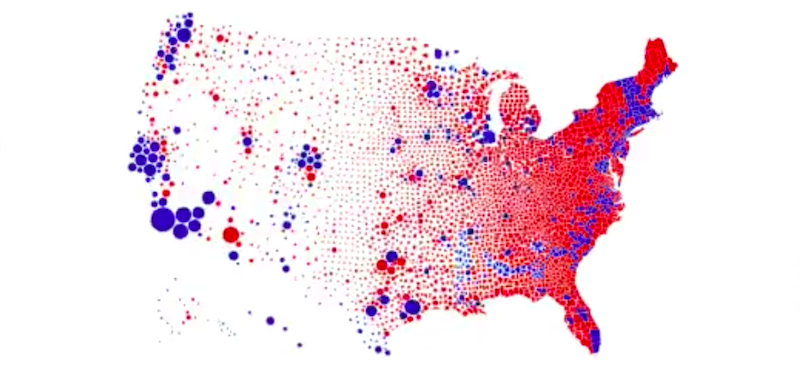

The map that has gone viral in recent days is a good compromise, because respecting the geographical borders it represents the most populated areas with points of various sizes: but the differences between the different points are not easy to distinguish, not to mention that a map almost completely empty is not very pleasant.

The fact that we are talking about candidates winning STATES and not candidates winning VOTES is the problem.

The land does not vote, the people do.

Abolish the electoral college.#AbolishTheElectoralCollege pic.twitter.com/mUnvlVCbUl– Justin L. Matthews ???? ️ ???? (@justinlmatthews) November 4, 2020

There are no simple solutions: using different colors could confuse readers or viewers (red and blue have been associated with Republicans and Democrats for several years now), while coloring uninhabited areas white would not eliminate the impression that red prevails anyway. Even playing with the shadows wouldn’t do much: in recent days a colorful map has been circulating that has abandoned the traditional blue and red in favor of purple: reddish if the state voted overwhelmingly for Republicans, bluish in the case of Democrats. But such a map takes several seconds, if not minutes, to be interpreted, without satisfying the need for immediacy that is required of electoral maps.

Our research has found that the red and blue political maps of the USA create a higher perception of polarization and more political stereotypes, compared to the more accurate purple maps.

Thanks to @geealbers for this new website: https://t.co/PtMT36CWqF pic.twitter.com/3hFuQMQPaQ

– Sara Konrath (@SaraKonrath) November 6, 2020

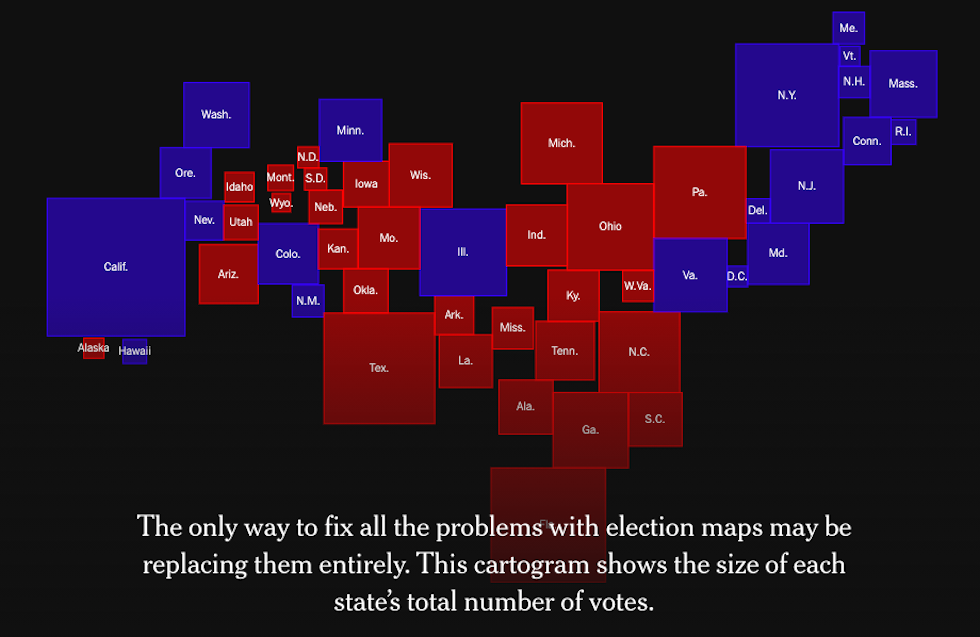

To accurately represent the population of each state, that is, the yardstick by which each state has its constituents at its disposal, one possible solution would be to abandon any ambition for geographic precision, or close to it.

For example, this is the electoral map showing the final predictions of Five thirty eight for the 2018 midterm elections: Each of the 435 constituencies is represented by a colored hexagon with various shades of red and blue – but any adherence to the geographic shape of the United States is lost. too al Jazeera used a similar one these days on its home page.

(Five thirty eight)

The best compromise, at least according to the New York Times – You plan to use small squares for each state, varying in size based on population or large voters, and make sure your profile vaguely resembles the shape of the United States. But even in this case, the result leaves something to be desired.

(New York Times)

A solution, suggested for example by the journalist from Vox Soo Oh, it could mean continuing to use geographically accurate maps, perhaps with a few tricks to correct the most glaring distortions, and contextualize them better: that is, make them interactive or present data and information in a visible way that can help the reader understand them better. Many of these things can be found on the map that has taken up much of the home page of the New York Times, or the one edited by Financial times.

(New York Times)

[ad_2]