[ad_1]

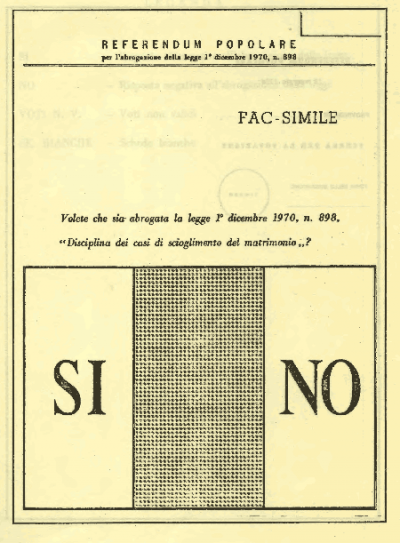

The law that introduced divorce in Italy was finally approved by the House on December 1, 1970, on Tuesday, at the end of a parliamentary session that lasted more than 18 hours. It was almost six in the morning and the voting had started at ten the day before. Law number 898 is known as “Fortuna-Baslini”, after the name of the two deputies, Loris Fortuna (socialist) and Antonio Baslini (liberal), the first signatories of the bills that were combined during a long approval process after years of conflict that continued in subsequent years and after the reform was called for and supported by women’s movements and radicals outside parliament.

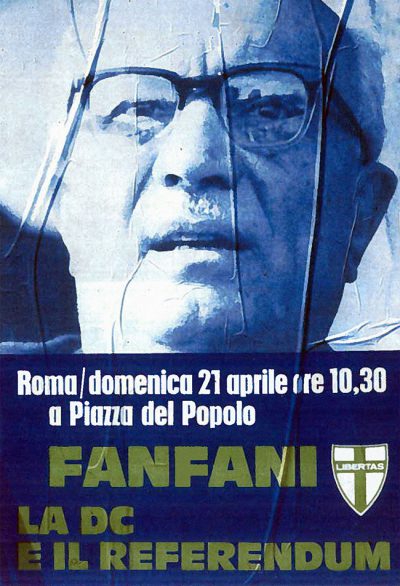

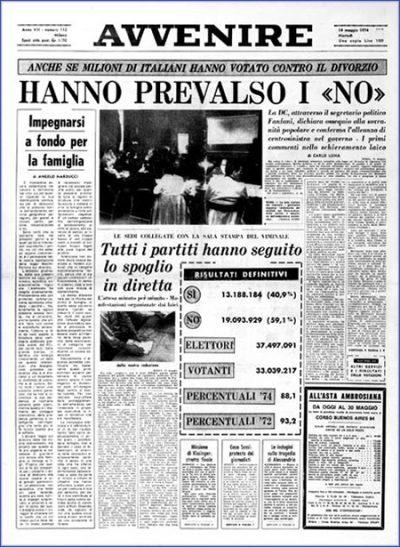

In 1974, after 1,300,000 signatures were deposited in the Supreme Court, a referendum was held to repeal the law. It was the first in the history of the Republic and was promoted by the Christian Democrats of Amintore Fanfani, the secretary. The vote took place on May 12 and 13 and more than 33 million people went to the polls, 87.72 percent of those who were entitled: the “no” that confirmed the divorce obtained 59.30 percent , the “yes” 40.7 and the Baslini-Fortuna was definitively confirmed. Future he titled: “It did not prevail”, recalling in the buttonhole that millions of Italians had voted against it. “Great victory of freedom,” he replied. Unit, taking up the words of the Italian Communist Party secretary Enrico Berlinguer: “It is a great victory for freedom, reason and law, a victory for Italy that has changed and that it wants and can continue.”

Since the unification of Italy the initiatives to include divorce in the Italian legal system, at least ten, were rejected mainly due to the influence of the hierarchies of the Catholic Church. In 1878 the deputy Salvatore Morelli tried it and for that reason he was represented in a cartoon surrounded by women dressed as men with cigars and cylinders. In 1902 the Zanardelli government drew up a proposal that, however, was never approved. Then there was the war, fascism, the Lateran Pacts and it was over thirty years before a divorce law was questioned. Italy remained one of the few European countries in which the indissolubility of marriage was in force (if not by death). The legal institution of judicial separation was contemplated: that is, a judge could recognize that two people could no longer live together, but those same people had to remain linked by the obligation of fidelity and mutual assistance: they could therefore not form a new family. Instead, it was possible to obtain the cancellation through the Sacra Rota, but only in some cases and only for those who could pay for the entire procedure.

Since the unification of Italy the initiatives to include divorce in the Italian legal system, at least ten, were rejected mainly due to the influence of the hierarchies of the Catholic Church. In 1878 the deputy Salvatore Morelli tried it and for that reason he was represented in a cartoon surrounded by women dressed as men with cigars and cylinders. In 1902 the Zanardelli government drew up a proposal that, however, was never approved. Then there was the war, fascism, the Lateran Pacts and it was over thirty years before a divorce law was questioned. Italy remained one of the few European countries in which the indissolubility of marriage was in force (if not by death). The legal institution of judicial separation was contemplated: that is, a judge could recognize that two people could no longer live together, but those same people had to remain linked by the obligation of fidelity and mutual assistance: they could therefore not form a new family. Instead, it was possible to obtain the cancellation through the Sacra Rota, but only in some cases and only for those who could pay for the entire procedure.

The long parliamentary process on divorce began when the socialist deputy Loris Fortuna – during the fifth legislature of the Colombo government, exponent of the Christian Democracy – presented in October 1965 a bill on “Cases of dissolution of marriage”. The confrontation was immediately very violent, between a secular party that supported the Fortuna project and the Catholic deputies who came to denounce its “revolutionary content.” On the one hand, there was the intransigence of the DC, the Italian Social Movement and the monarchists, on the other the favor of the PSI, the radical and women’s movements and the UDI, the Union of Italian Women, while the PCI After much uncertainty on whether or not to commit to the issue, he took a clear position in favor only in the middle of the referendum campaign.

In 1968, Liberal MP Baslini introduced a new bill, more moderate than Fortuna’s proposal. But as both texts provided for the introduction of the institution of divorce in the Italian legal system, they were joined in the same bill in April 1969, which was then voted on by Parliament.

In 1969, in a special on RAI, the issue of divorce was introduced as follows: “Today there is a lot of pressure for a totally new law to be included in Italian family law: the divorce law. Divorce is a difficult discourse that raises a whole series of questions: does the end of conjugal indissolubility hurt and weaken the concept of family or, on the other hand, allow the recovery of those painfully affected? Does it protect morale or does it offend them? Does it protect children or endanger their social stability? ». Fortuna, in the special, said that he wanted to adapt the “archaic legislation in the field of family law to the new conditions.” He said it was a “choice of freedom” (“No one will be forced. Those who in their own conscience think that they should not do it, will not do it”) and spoke of the need to “find a remedy for situations completely blocked by reality. “. Nilde Iotti, on November 25, 1969, when the legislative process was nearing its end, asked the Chamber of Deputies to speak and gave a speech that became famous in the history of women’s rights:

“In the past, the family has essentially constituted a moment of aggregation of human society, for very diverse reasons, in particular the location of the woman, the procreation of children, the transmission of goods. These were the fundamental reasons that led to the establishment of the family; that is, the family has responded, in some way, to the search for the social position of individuals. (…) It seems to us that what in the modern world pushes people towards marriage and the formation of the family, what makes the formation of the family moral in the popular conscience, is in the first place the existence of feelings. (…) This, I think, is the moral basis of marriage today. (…)

(…) You will see, ladies and gentlemen: no matter how strong the feelings that unite a man and a woman, at any time, but above all I would say, in today’s world, they can also change; and when feelings cease to exist, for the reasons explained above, the moral foundation on which family life is based ceases to exist. Therefore, we must admit the possibility of separation and dissolution of marriage.

(…) Of course, we know very well that when a family dissolves, the condition of the children becomes extremely serious; we cannot ignore it, as if this fact did not exist. But I think there is a fact that precedes this and that we cannot forget, and that is that children are important in the life of a family unit, but the protagonists of the family are not the children: they are the father and the mother. It is the latter who determine family life and its moral level; not the presence of children.

(…) The Church itself has never questioned the presence of children in its sentences of marriage annulment. This has never been a reason that has prevented ecclesiastical courts from passing sentences of nullity of marriage. (…) Finally, ladies and gentlemen, I would add that the condition of children in a family united by force, in a family where violence or, worse – I mean worse – indifference, are the basis of the spouses’ relationships , is the worst. possible, and causes the devastation of his personality.

After the first approval in the Chamber (it took 33 sessions and the interventions of 133 deputies), the discussion went to the Senate, which voted on October 9, 1970. The amended text returned to the Chamber, which on December 1, 1970 approved it. definitely (with 319 yes and 286 no, out of 605 voters and present). Divorces in the first year of application of the law were 17,134, the following year 31,717.

Meanwhile, on August 31, 1968, the Leona government had promoted a bill that, based on Article 75 of the Constitution, allowed the repeal of referendums. On December 2, the newspaper Future launched a call to immediately call a referendum to cancel the recently passed divorce law. The Christian Democrats and the Italian social movement, speaking of the law as the first step towards the dissolution of the society and its foundation, immediately took action for the repeal referendum. And the campaign was, again, very tough. Republican Giorgio Almirante, leader of the Social Movement, had a poster printed with the words “Vote yes against the friends of the Red Brigades on May 12.” Shortly before the vote, Amintore Fanfani said: “Do you want a divorce? Then you should know that the abortion will come later. And after that, gay marriage. And maybe your wife will let you run away with the servant! ». And on Sunday May 12, Pope Paul VI, looking out the window at the noon prayer, declared: “We are not going to break now the silence of this day, destined for Italians to a decisive reflection, in relation to one of the most serious duties for believers and for citizens, with regard to the good of the family. We only invite you to put this express intention, imploring wisdom, in our prayer to Our Lady of today “.

Meanwhile, on August 31, 1968, the Leona government had promoted a bill that, based on Article 75 of the Constitution, allowed the repeal of referendums. On December 2, the newspaper Future launched a call to immediately call a referendum to cancel the recently passed divorce law. The Christian Democrats and the Italian social movement, speaking of the law as the first step towards the dissolution of the society and its foundation, immediately took action for the repeal referendum. And the campaign was, again, very tough. Republican Giorgio Almirante, leader of the Social Movement, had a poster printed with the words “Vote yes against the friends of the Red Brigades on May 12.” Shortly before the vote, Amintore Fanfani said: “Do you want a divorce? Then you should know that the abortion will come later. And after that, gay marriage. And maybe your wife will let you run away with the servant! ». And on Sunday May 12, Pope Paul VI, looking out the window at the noon prayer, declared: “We are not going to break now the silence of this day, destined for Italians to a decisive reflection, in relation to one of the most serious duties for believers and for citizens, with regard to the good of the family. We only invite you to put this express intention, imploring wisdom, in our prayer to Our Lady of today “.

On the other hand, PCI, PSI, Radical Party, secular associations and women’s movements continued to defend “freedom of choice” and supporting the “no” to oppression and exploitation within the family. The divorce was won and since then feminist movements began to ask the question of the political management of what would happen next: “Any cause of separation or divorce must become a dispute over domestic work,” they argued.

The 1970 law was reformed in 1978 and 1987 when – thanks to the then president of the Chamber Nilde Iotti who managed to obtain the unanimous agreement of all the groups – the time needed to reach the sentence was reduced from five to three years. definitive. In 2015, a bill was approved that introduces the so-called short divorce, which reduces the period between separation and divorce, and anticipates the dissolution of the patrimonial community.

(Four electoral carousels against the repeal of divorce, with Gianni Morandi, Pino Caruso, Gigi Proietti and Nino Manfredi: invited to vote no. The fifth carousel was filmed in the classroom of a Roman primary school during a civics lesson)

[ad_2]