[ad_1]

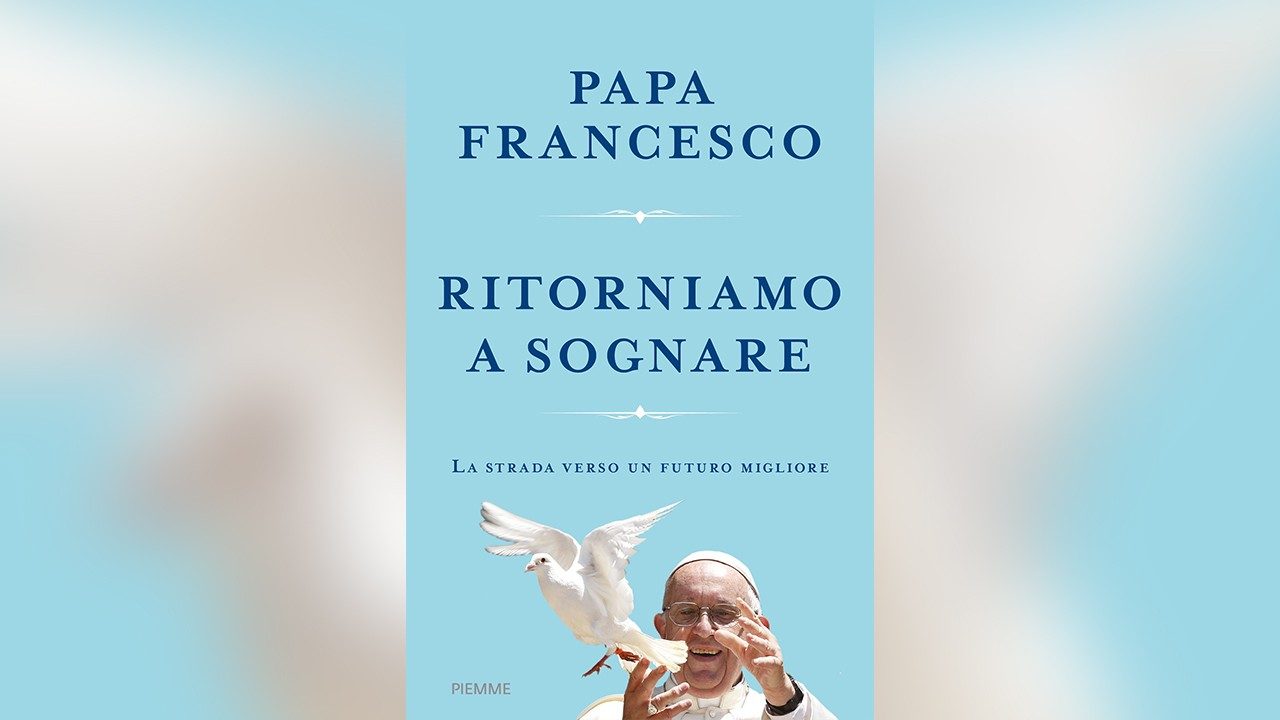

We published an excerpt from the book “Let’s dream again” (Piemme) written by the Pope with the journalist Austen Ivereigh, in bookstores since December. The song was anticipated by the La Repubblica newspaper in today’s newsstand edition

POPE FRANCESCO

In my life I have had three “Covid” situations: illness, Germany and Córdoba.

When I contracted a serious illness at age twenty-one, I had my first experience of limits, pain, and loneliness. Changed my coordinates. For months I didn’t know who he was, if he was going to die or live. Even the doctors didn’t know if he would make it. I remember one day I asked my mother, hugging her, to tell me if I was going to die. He was attending the second year of the diocesan seminary in Buenos Aires.

I remember the date: it was August 13, 1957. A prefect took me to the hospital, realizing that I did not have the type of flu that is treated with aspirin. First they took a liter and a half of water from my lung, then they let me fight between life and death. In November, I had surgery to remove the upper right lobe of my lung. I know from experience how people with coronavirus feel when they struggle to breathe on a ventilator.

I remember two nurses in particular from those days. One was the head nurse, a Dominican nun who had been a teacher in Athens before being sent to Buenos Aires. I learned later how, after the doctor left after the first exam was finished, he told the nurses to double the dose of the treatment he had prescribed (penicillin and streptomycin) because his experience told him I was dying. Sister Cornelia Caraglio saved my life. Thanks to his regular contact with the sick, he knew better than the doctor what patients needed and had the courage to take advantage of that experience.

Another nurse, Micaela, did the same when I was in pain. He secretly gave me extra doses of sedatives, outside of the scheduled time. Cornelia and Micaela are in heaven now, but I will always be in their debt. They fought for me until the end, until I recovered. They taught me what it means to use science and know how to go further, to meet specific needs.

I learned something else from that experience: how important it is to avoid cheap comfort. People came to see me and told me that it would be okay, that I would never feel all that pain again: nonsense, empty words spoken with good intentions, but that never reached my heart. The person who most deeply moved me, with her silence, was one of the women who marked my life: Sister María Dolores Tortolo, my teacher as a child, who had prepared me for my first communion. He came to see me, took me by the hand, gave me a kiss and was silent for a while. Then he said, “You are imitating Jesus.” There was no need for me to add anything else. His presence, his silence, gave me deep comfort.

After that experience, I made the decision to speak as little as possible when visiting patients. I just take her hand.

[…]You could say that the German period, in 1986, was the “Covid of exile”. It was a voluntary exile, because there I went to study the language and look for the material to finish my thesis, but I felt like a fish out of water. I ran for a few walks to the Frankfurt Cemetery and from there you could see the planes taking off and landing; I was nostalgic for my homeland, for returning. I remember the day Argentina won the World Cup. I had not wanted to see the game and knew that we had only won the next day, reading it in the newspaper. No one in my German class mentioned it, but when a Japanese girl wrote “Viva Argentina” on the board, the others laughed. The teacher came in, said to delete it, and closed the subject.

It was the loneliness of a single victory, because there was no one to share it with; the loneliness of not belonging, which makes you a stranger. They take you out of where you are and put you in a place that you do not know, and in that while you learn what really matters in the place you left.

Sometimes uprooting can be a radical healing or transformation. This was my third “Covid”, when I was sent to Córdoba from 1990 to 1992. The roots of this period go back to my way of governing, first as a provincial and then as a rector. He had certainly done something good, but at times it had been very hard. In Córdoba they did me the favor and they were right.

I spent a year, ten months, and thirteen days in that Jesuit residence. I celebrated mass, confessed, and offered spiritual direction, but never went out except when I had to go to the post office. It was a kind of quarantine, isolation, as has happened to many of us in recent months, and it did me good. It led me to develop ideas: I wrote and prayed a lot.

Until that moment in the Society I had had an orderly life, based on my experience first as a novice master and then in the government from 1973, when I was appointed provincial, until 1986, when I concluded my mandate as rector. I had adapted to that way of life. An uprooting of that type, with which they send you to a remote corner and put you as a substitute teacher, upsets everything. Your habits, your reflexes of behavior, your reference lines stuck in time, all this has gone wrong and you have to learn to live from scratch, to rebuild existence.

About that period, today, three things particularly catch my attention. First, the ability to pray that was given to me. Second, the temptations I felt. And third, and the strangest thing, that I read the thirty-seven volumes of the History of the Popes by Ludwig Pastor. I could have chosen a novel, something more interesting. Where am I from now, I wonder why God inspired me to read that same work at that time. With that vaccine the Lord prepared me. Once you know that story, there is not much that surprises you with what is happening in the Roman curia and in the Church today. It helped me a ton!

The “Covid” of Córdoba was a real purge. It gave me more tolerance, understanding, the ability to forgive. It also left me with a new empathy for the weak and helpless. And patience, a lot of patience, or the gift of understanding that important things take time, that change is organic, that there are limits and you have to operate within them and at the same time keep your eyes on the horizon, as you did. Jesus, I have learned the importance of seeing the big in the small and paying attention to the small in the big things. It was a period of growth in many ways, like sprouting again after a complete pruning.

But I must be on guard, because when you fall into certain defects, certain sins, and you correct yourself, the devil, as Jesus says, comes back, sees the house “swept and adorned” (Luca 11:25) and is going to call seven other spirits worse than himself. The end of that man, says Jesus, becomes much worse than before. I have to worry about this now in my office of government of the Church: not to fall into the same defects as when I was a religious superior.

[…] These were my main personal “Covids”. I learned that you suffer a lot, but if you let me change you, you come out better. But if you raise the barricades, it comes out worse.TO DREAM AGAIN. English translation copyright © 2020 Austen Ivereigh.

All rights reserved.

Published for PIEMME by Mondadori Libri SpA

© 2020 Mondadori Libri SpA, Milan

Published by agreement with Berla & Griffini