By Sarah Rainsford

BBC News, Nizhny Novgorod

The day Irina Slavina decided to kill herself, Alexei saw something unusual in his wife. It was her mother’s 70th birthday and Irina baked an apple Charlotte to celebrate it.

At 13:34 Alexi rang her mobile and the couple spoke briefly: “Normal thing, like when he comes back.” Two hours later, he received a call that Irina had set herself on fire under the walls of the local Interior Ministry.

Read his last post on Facebook: “I ask you to blame the Russian Federation for my death.”

Heavy opposition

In Nizhny Novgorod, km00 km (250 miles) east of Moscow, people close to Irina Slavina told themselves that no one knew what the journalist was thinking, so he could not stop.

But they are convinced that it was an act of deliberate political protest, not frustration.

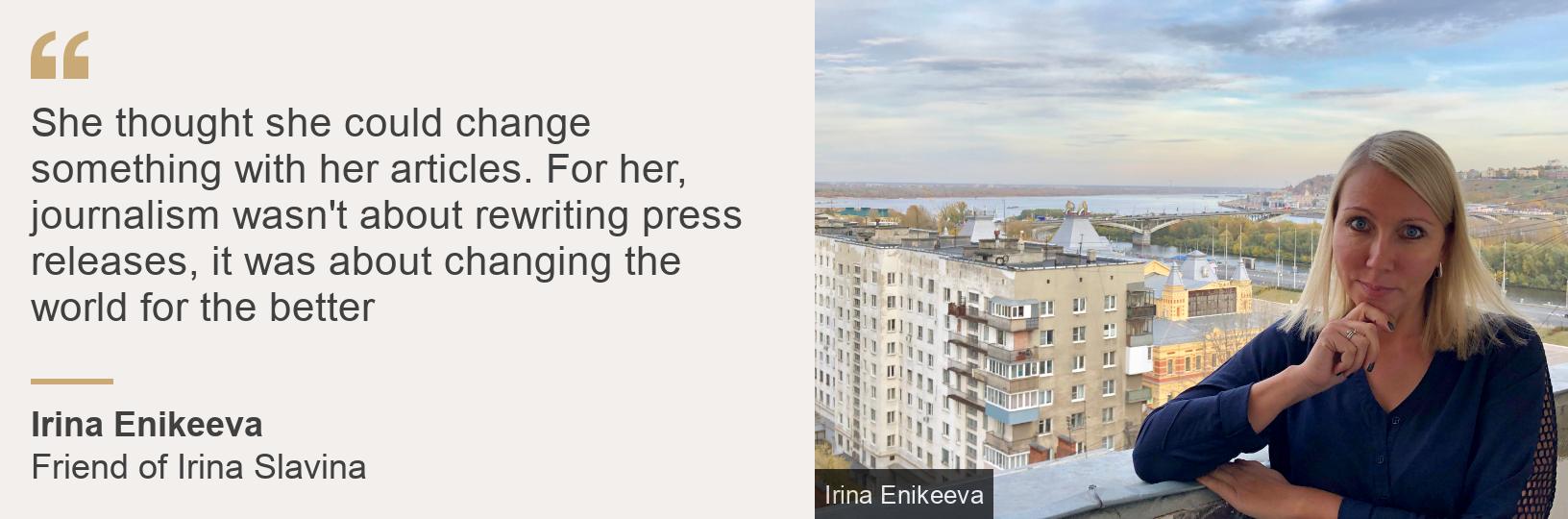

“Irina Slavina and depression have nothing in common!” Her friend of many years, Irina Enkiwa told me. “She was positive, an ‘enthusiastic’; a woman full of kindness, warmth and light.”

Shortly after his death, video footage from CCTV cameras apparently circulated circ online. It clearly shows Irina Slavina in front of the huge, concrete headquarters of the Interior Ministry.

She sits between three bronze figures on the bench: a monument to Russian police officers for ages.

The flames first appear on his left arm and then run into his sleeve and engulf his entire body in seconds. One passenger shed tears from his jacket and tried to extinguish the fire in panic, but the dead woman pushed him twice before he broke down.

‘Will my sacrifice be meaningless?’

“It was clear he was determined to do this,” said another friend, pro-democracy activist Mikhail Aosilevich. “The fact that she decided on the extreme act is not a suicide, but a kind of protest: calculated and planned.”

A year ago, Irina also shared the idea on Facebook. She asked, if she set herself well, would she bring Russia “a little faster into a brighter future? Or would my sacrifice be meaningless?”

Image copyright pyriteIrina Enkiwa

Her readers thought it was a joke.

Irina Slavina, a mother of two who met her husband as a teenager, walking their dogs, began her professional life as a school teacher. That was a bad fit: Alexei told me she didn’t like the rules.

‘Changing the world for the better’

So, in 2003, he marched to a local newspaper and applied for a job.

Alexi says she felt “free” in her new role.

But with President Vladimir Putin’s presidency leading to greater acceptance of press freedom in Russia, Irina’s principles became a problem and she was eventually fired. “All the pressure on how to spin stories for the officers got on his nerves,” says his friend.

So in 2015, she was supported by the missile Iosilevich, Koza. Founded the press and began to have a reputation as the only independent journalist in the city. Others might write weird, hard hit-writing articles, but Slavina was persistent and unpredictable.

Officers soon took note.

-

Russian editor dies after setting himself on fire

- Journalists are shocked to find the enemy inside Russia

- The national debate begins with the death of a Russian girl

Change proceedings?

“He wrote about the atrocities committed by the security forces and officers. He wrote strict, straightforward and honest reports and he didn’t like it. So it was in his eyes,” says Gwynn instead.

The lawyer has the thickest paper in his office fees from all the court cases in which he defended himself.

He was accused of staging illegal protests, working for a banned pro-democracy group when reporting on the political stage and spreading fake news when he wrote about the local outbreak of the coronavirus.

When she – in colorful language – objected to Stalin on a plaque, he was fined 70,000 rubles (£ 700; 70 770) for insulting the feelings of local communists.

“There were 10 or 12 administrative cases against him and they all ended in fines,” says Gwynn of AVJ. “Over the past 18 months, the proceedings have been ongoing.”

Once seen as the leading light in the transition to Russian democracy, Nizhny Novgorod has since become a “swamp” of indifference, troubles civil society activists.

In contrast, it is now notorious for a very active “anti-terrorism” department in the local police, largely focused on suppressing political opposition.

Cosa. With the meager income of the press, he had to crowdfund to pay heavy fines.

In a short clip posted on YouTube, “Of course, I associate it with my journalism.” “I see it as revenge.”

Her husband, a former sailor, says the two did not discuss her journalism in detail many times. But Alexei admitted that the court cases were a great stress on Irina and ‘in our country, impossible to win’.

“She was under a lot of pressure to tell the truth. It really bothered her,” he admits.

The last straw

The day before Irina took her life, the pressure increased.

He and Alexi were woken up at 6 a.m. by 12 investigators at the door and armed police. For more than four hours, they searched and flattened the flat.

It was part of a criminal case against Irina’s friend, Mikhail Iosilevich, a “pastor” who holds so-called weekly gatherings in his humor at the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster to promote free thinking.

But Mikhail, who wears a calendar on his head at the meetings, is now accused of threatening Russia’s state security after hosting training sessions for local election monitors. Investigators claim the program was run by Open Russia, a group banned for ties to President Putin’s longest-serving critic-in-exile, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Mr. Iosilevich and Open Russia deny it.

Irina Slavina and six other activists have been listed as “witnesses” in the case, often just one step towards legal action. Some believe it is designed to cow all the critics of Nizhny; Others, including Irina, have linked it to allegations of high park corruption in protest of the local park’s reconstruction.

For the editor of Koza.Press, the police search seems to be the last straw.

“It was another slap in the face from our country,” he tells me over the phone as he walks out of town with his family to “get away from everything”.

“Irina was really impressed. She got angry.”

Hours after Irina’s death, the local branch of the investigation committee denied any link between her suicide and the search for her flat. The journalist did not personally make any allegations, he points out.

Dham towards iniquity

The first couple of nights after the journalist’s death, city cleaners picked up flowers scattered on the spot. They let them live right now, turning a memorial for law enforcement into a temple for a woman who fought abuse and injustice – including at her level.

Two officers patrol the pavement, keeping an eye on those who are watching and contemplating.

Some have not even heard the news; Others are shocked and terrified and some wonder if she is trying to shock the city with her indifference.

Irina’s husband can’t explain it, and says he’s not trying for now.

“He won’t bring it back, I just have to accept his decision,” he says. “But I don’t want his death to be in vain.”

Are you impressed with it?

If you or someone you know is experiencing emotional distress, the Samaritans Helpline is available 24 hours a day for anyone struggling to cope in the UK. It provides a safe place to talk where calls are completely confidential.

Free Phone: 116 123

More details of the helpline can be found here.

Related topics

-

Russia

- Journalism