[ad_1]

Welcome to the political solution by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a weekly newsletter on Indian politics and politics. To receive it in your inbox every Monday, register here.

You can help support this newsletter and all the work we do at Scroll.in either by subscribing to Scroll + or contributing any amount you prefer to the Scroll.in Report Fund.

The big story: Ctrl-Alt-Delete

From May 10:

Covid-19 cases in India: 62,939 (down from 40,263 last week)

Recovered: 19,357 (instead of 10,885)

Deceased: 2,109 (vs. 1,306)

It is a cliche now to accept that India is reforming in a crisis.

The trope is most strongly related to the 1991 balance of payments crisis, which led to the process now commonly known as the “liberalization” of the Indian economy.

So this week, when the Indian states announced a series of changes in labor laws, television channels and newspapers spoke of important “reforms” in the midst of the coronavirus crisis and of the chief ministers “feeding the engine “and” paving the way for the rest of India to follow. “

Due to the 1991 example, the term “reforms” tends to evoke memories of the dismantling of the restrictive Raj licensing permit (which, as Rahul Jacob’s excellent piece explains, is actually making a comeback) and changes to the laws allowing private business To thrive. The English media generally represents changes that are indisputably beneficial to Indians.

But can you use the word “reforms” to describe the actions of Uttar Pradesh under Chief Minister Adityanath? To attract investment, Adityanath is giving companies and factories in his state a three-year regulatory holiday. The purge: Work, If you want.

“The Uttar Pradesh government passed an ordinance exempting companies from the scope of almost all labor laws for the next three years, to boost investment in the state, affected by Covid-19 …

The government had approved the “Uttar Pradesh Temporary Exemption from the Ordinance on Certain Labor Laws, 2020” to exempt all establishments, factories and companies from the scope of all but four labor laws, for three years. “

Laws related to industrial disputes, including layoffs and severance pay, and workers’ working conditions, health and safety mandates, the maintenance of facilities like drinking water, canteens, bathrooms, and day care centers, and interstate regulation of workers are missing for the next three years. The list is long.

As expected, this has exhilarated people who believe that labor laws are the main barrier holding back Indian industry. (It doesn’t matter the fact that many of those who hold this belief can’t really point to laws that have been shown to be restrictive, as our 2014 report shows.)

Meanwhile, those who pay attention to real working conditions are horrified. This “goes back 100 years,” said one. Even the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, the labor wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the parent organization of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, has criticized the decisions. They are a “bigger pandemic,” said the Sangh.

And here’s a comment from Gautam Chikermane of the Observer Research Foundation and businessman Rishi Agrawal, neither of whom is exactly a bleeding-hearted labor activist:

“We wonder what this policy will deliver to Uttar Pradesh. Even if we believe that these suspensions are fine and approved by the Union and the judicial meeting, we do not understand what Adityanath will get or how Uttar Pradesh will benefit from designing a policy for only three years or how such a policy will attract long-term capital. Investors need political stability, consistency and predictability. A three-year window of regulatory concessions is of no use to any serious new investor. ”

Chikermane and Agrawal compared the Uttar Pradesh movement to the changes implemented by the Madhya Pradesh government, insisting that the latter’s policies make much more sense.

Faced with Adityanath’s demolition ball, Madhya Pradesh Prime Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan is carrying out a more specific demolition of labor laws. The new state rules aim to significantly reduce the regulatory processes that a company must undertake, particularly if it is new.

Critics have long discussed that many of these laws really go against labor interests, and instead only allows rent search behavior. These people believe that repealing some of those laws will allow private industry to prosper, giving workers more options and benefits.

But, in addition to removing some of the regulatory requirements, Madhya Pradesh will allow companies to hire contract workers for a longer period, it will allow them not to recognize unions for collective bargaining in a number of sectors such as textiles, cement and the automobile, and not providing any mechanism to raise industrial disputes for new companies.

Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh are not the only ones. Other states have eliminated the eight-hour workday and are trying various changes to labor laws.

Shankar Gopalakrishnan, who studies labor issues, has a useful thread on the standard narratives surrounding changes in labor law in India and how the laws harm workers in the unorganized sector, even if they do not apply to them.

the Economic times‘TK Arun argues that the decisions reflect what kind of aspirations the Indian states seem to have: “If the ambition is to set up sweatshops that produce products to sell in the local weekly market, you have the kind of labor laws that Uttar leaders Pradesh and champion of Madhya Pradesh. ”

And Saurabh Bhattacharjee reiterates in Scroll.in, “A study of four states, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, conducted by the VV Giri National Labor Institute found that “amendments to labor laws failed to attract large investments, boost industrialization or job creation” . Regression analysis studies of the Indian experience have shown that “growth in labor market flexibility has no statistically significant influence on job growth.”

This context is important because several states are making these changes with the idea of attracting business that would have otherwise gone to China, which we wrote about two weeks ago.

At least some of this seems like an illusion, considering the economic mismanagement that India has seen in the past six years, coupled with the immense state arbitrariness that companies face during the shutdown. This does not exactly reflect the ease of doing business.

There is an unspoken aspect of the trope “India’s reforms in crisis.” Generally, it means that it is also a time when opposition to these changes, the kind of backsliding that makes it difficult for those laws to be changed in normal times, has been lifted. That can be seen as a good thing if its effect is to end rent-seeking behavior or undermine vested interests.

But when it comes to workers at a time when people just don’t have a chance to take to the streets to voice their opposition, this might seem like cruel exploitation to many people. And it tells us even more about how pandemic politics can unfold, the subject of last week’s newsletter.

Half lost

The Center under Prime Minister Narendra Modi during this crisis has been full of contradictions, if not absolute arbitrariness. One day, angry, he tells Kerala that it is not allowed to open bookstores. Two days later, it makes opening bookstores legal.

The central government has tried to dictate much of how India has responded to Covid-19, a damaging centralized approach that we wrote about a few weeks ago. However, it has been absurdly absent when it comes to other issues.

The crisis of migrant workers is instructive.

Last week Karnataka acknowledged that she sees migrant workers as machines or beasts of burden, not as citizens. Immediately after a meeting with real estate developers, Chief Minister BS Yediyurappa decided to cancel the trains for this vulnerable group to go home. As I wrote, comparisons to bonded labor and the beginning were not exaggerated.

BJP Member of Parliament Tejasvi Surya (whose past intolerance has been so shameful that the Indian government asked Twitter to remove one of his posts) sold the idea as a “bold move” that would help migrant workers “restart their dreams”.

Fortunately, public pressure resulted in the reversal of the policy.

Other states have also taken care of everything from the cost of screening to the responsibility of providing care to migrants as they try to get home in the midst of this crisis. And as a result, with an even greater departure on foot or on dangerous road trips, we received news of a freight train with more than 16 workers and an overturned truck that killed six.

Meanwhile, the Center, which is entirely responsible for interstate travel and whose logical role would include defending citizens if individual states quarrel, has left several top ministers to deal with this politically complicated situation. This fits in with the Modi-gets-the-credit, states-get-the-culme approach we’ve seen.

Center 2 missing

It’s been 45 days since the Ministry of Finance last announced a package to address the economic consequences of India’s harsh closure measures, and that was primarily a reworking of existing schemes to give food and cash to poor. There have been reports for weeks about a real stimulus package for industry and small businesses. Without a doubt, one is in the works. However, the delay has already cost India.

Meanwhile, KV Subramanian, Prime Economic Adviser to the Prime Minister, believes that India’s GDP growth will be 2% this year, when most other countries expect zero or negative growth. (For context, his prediction for last year’s growth was two percentage points below what even the finance ministry was finally expecting.) His “no free lunch” speech has left many wondering if India will seek a fiscally conservative response to the crisis.

Shah’s health

Amit Shah is unhappy.

The Union Minister of the Interior has been relatively silent for the past few months, returning to messages from the Center about the Delhi riots. This was a considerable change compared to 2019, when Shah almost seemed more prominent than Modi.

The Covid-19 crisis has also seen Shah at most operating in the background, with the occasional photoshoot or press release from the Home Office. This led to some circulating theories, and people speculated that it was not right.

Now some of those people have been detained. And Shah released a statement asking people to take care of their own affairs, adding that he believes speculation about people’s health only strengthens them.

End of confinement?

The next deadline for the Center to decide how India copes with the coronavirus crisis is May 17, when the third phase of the blockade is about to end. Modi will speak to top ministers on Monday, which should offer an idea of what the way forward is like.

Most indications suggest that, after more than seven weeks of closure (with the last two seeing considerable relaxation in the extremely harsh measures of the first five), India will open up. Indian Railways has already said it will restart some services.

However, this will take place despite coronavirus cases continuing to grow and questions about whether enough was done to prepare in the meantime.

We consider, in this newsletter a few weeks ago, the complication of India moving to an “early” close, when it had only 500 cases. That seems even more marked now. As I write in this long look at the shutdown and what comes next, the simple answer as to why India is opening up now might not be due to specific gains against the virus or health readiness, but simply that it cannot afford the luxury of closing for much longer.

“It is important that we learn to live with the virus,” said joint secretary of the Ministry of Health, Lav Agarwal, last week, admitting the same.

Remains and debris

Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, 87, has been admitted to the hospital after he complained of concern. Former Chhattisgarh Prime Minister Ajit Jogi, 74, fell into a coma.

Indian and Chinese troops slammed their fists into the Sikkim border, although the situation appears to have been resolved. India’s Department of Meteorology will now offer weather forecasts for areas of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, resulting in even more chatter between India and Pakistan than usual, especially for Gilgit Baltistan.

The political entanglement of Maharashtra’s head of government, Uddhav Thackeray, the fact that he is not actually an MLA yet, appears to have been resolved. A gas leak at a plant that was reopening after the shutdown in Andhra Pradesh killed 11 people. Moody’s says that India’s GDP growth will be zero this year and that the country’s sovereign rating could be further lowered.

Ground report

Shoaib Daniyal has a report on how West Bengal is only paying attention to the idea of recovering its migrants, as the state fears further spread of Covid-19 if large quantities return.

The piece has this excellent anecdote, when a Gujarat official asks Daniyal to do interstate coordination:

“To make matters worse, Bengal has not responded to requests from other states when it comes to recovering Bengali workers. On May 4, Karnataka complained that Bengal refused to consent to the trains. Maharashtra made the same accusation on May 6.

Harshad Patel, the Gujarat government’s nodal officer for West Bengal migrants, accused the Trinamool government of requests for stone walls to accept migrant trains. “We cannot connect with them,” Patel complained when contacted by Scroll.in. ‘There is no response or consent from West Bengal. We cannot send trains until they agree. “

“Ask them to at least respond,” he continued. “If you consent, we can plan trains and request railways.”

As always, this is where I remind you to contribute to our field reporting fund, or subscribe to Scroll + if you want to help us ensure we can continue to provide you with quality journalism in these testing times. “

Linking

India is using criminal provisions for what is essentially an economic strategy. “Economic policy works well when there is a slow, intellectual, and consultative process to understand the issues, perform cost-benefit analyzes, find the least coercive intervention, and make small moves,” writes Ajay Shah in the Business Standard. “The Disaster Management Act, 2005, does not have these checks and balances.”

A massive repatriation effort is underway, as India attempts to bring citizens home from abroad. Although the Vande Bharat mission is being used to generate publicity for the Modi government’s efforts, it is fraught with challenges, writes Constantino Xavier in the Hindustan Times. Nikhil Eapen in Article 14 He writes about how ticket prices are too high for many Indians working in the Arabian Gulf.

We must pay close attention to how people save their money. In mintNiranjan Rajadhyaksha’s savings data will tell us what effect the crisis has on expectations for the future.

Is Nepal further falling out of India’s orbit? Gautam Sen explains why he thinks this is so New world ordereven when the two countries enter another map-based dispute.

Almost 40% of Aaadhar-based payments failed in April. Malavika Raghavan and Samir Shah write in mint on how this worsens the lives of the vulnerable.

“When all the smoke and dust is cleared, the state government’s finances will be in ruins.” This is what Pronab Sen says about Ideas for India, predicting that states will have to go downtown with the begging plate.

Should India allow the employment of MGNREGS workers in private agricultural activities? Roshan Kishore at the Hindustan Times He argues that it would be a non-inflationary way of supporting rural India.

Read this report on the “precarious” at the time of the pandemic. Forty economists offer an analysis of the trade and foreign policy effects of Covid-19 in India.

I can’t make this up

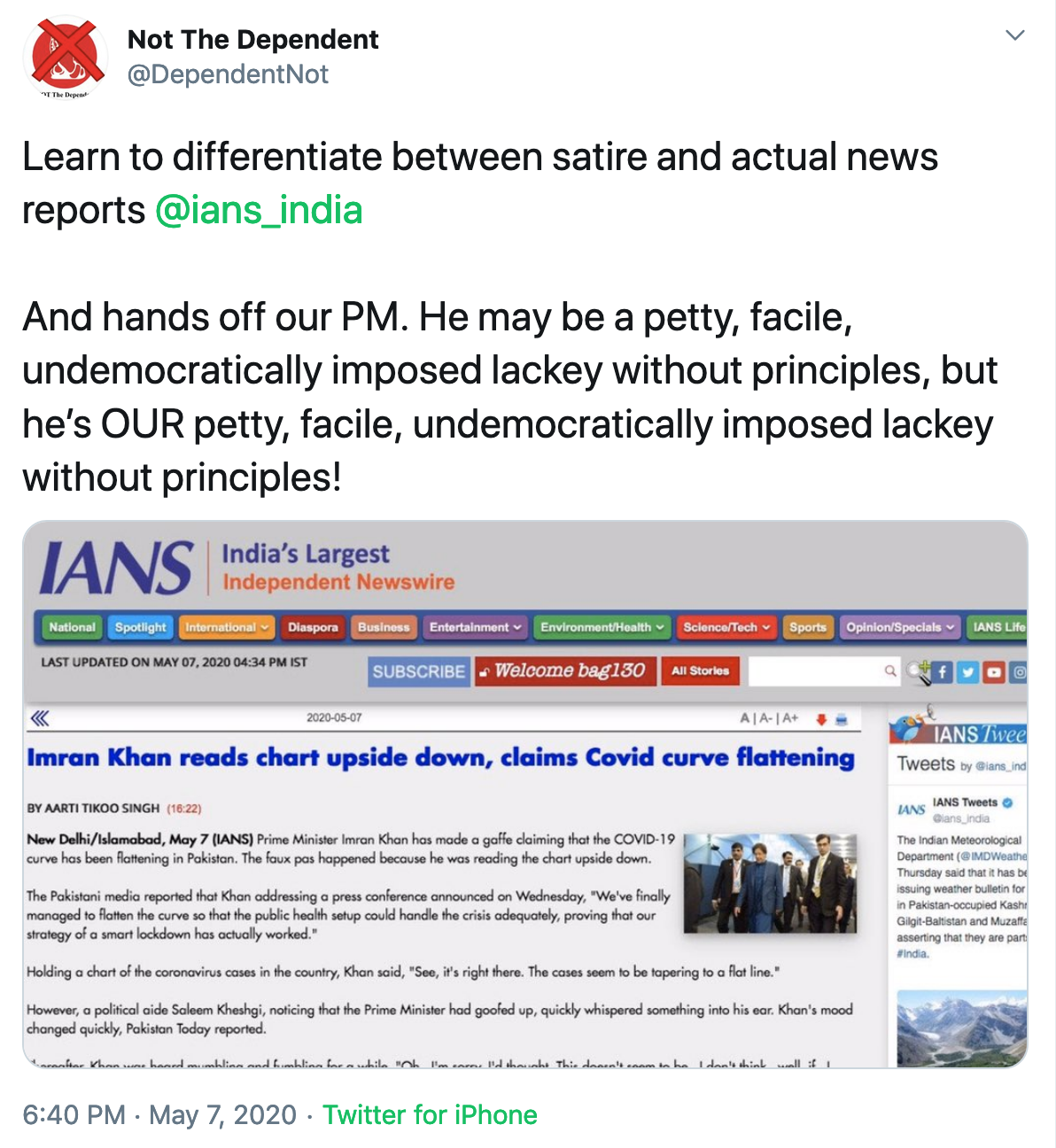

India’s IANS news service mistaken some Pakistani satire for genuine news, resulting in in this excellent tweet about Imran Khan:

If you find the political solution helpful, share and subscribe. And if we missed some useful links or tweets, write to [email protected]

.

[ad_2]