The forecast for Tuesday, March 23, showed wind gusts of over 40 miles per hour and sand storms hitting the north. Egypt. In fact, such weather is common in the Sinai desert at this time of year.

The Suez Canal, one of the most critical but precarious waterways on the planet, remained open. The ships began to form the daily convoy as the gusts increased. One of the largest container ships in the world, the Ever Given, joined it. The decision will reverberate around the world in a matter of hours.

At 7:40 a.m. local time, the mega-ship, loaded with containers that would stretch more than 120 kilometers (75 miles) from end to end and carrying everything from frozen fish to furniture, was stuck. Its connection to land would expose not only the complexities of navigating a man-made trench of water on a ship the size of the Eiffel Tower, but also the fragility of a global network of markets and economies that takes flow for granted. of goods through it. .

According to monitoring data and dozens of interviews with people in the industry, what is known is that Ever Given began crossing the 300-meter-wide channel while at least one other ship decided to stop due to high winds. The Ever Given also did not employ tugs, according to two people with knowledge of the situation, while the two slightly smaller container ships immediately ahead did.

Then there was the question of how fast it was going. As the ship began to move towards the sand, it seemed to accelerate, perhaps to correct itself, although it was too late and almost hit the shore. That served to later fit the steel hull deeper into the side of the canal. The gusts would also have compounded what captains consider one of the most difficult water crossings in the world.

“A few rides await you,” said Andrew Kinsey, a former captain who has sailed a 300-meter freighter through the Suez and is now a senior marine risk consultant at Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty. “It is such a small channel, the winds are very strong and you have a very small margin of error and great consequences if errors occur.”

It wasn’t a situation where you couldn’t candle, despite the fact that the wind was strong enough to close the nearby ports. Some vessels used tugs or other assistance, others simply passed without incident.

However, at least one ship decided to delay the canal trip. The day before the Ever Given landed, the Rasheeda was among the ships approaching the canal from the southern tip. Aware of the dangers of the looming sandstorm and loaded with liquefied natural gas from Qatar, the captain decided not to enter the canal after discussing it with other officials from Royal Dutch Shell Plc, which manages the ship, according to two people familiar with the situation.

The Suez Canal The authority said the lack of visibility in adverse weather conditions caused the ship to lose control and veer off. He has not commented further. Taiwan-based Evergreen Line, the ship’s time charterer, said by email that the Ever Given “was accidentally grounded after veering off course due to suspected sudden strong wind.”

The ship’s manager, Benhard Schulte Shipmanagement, said initial investigations suggest the accident was due to the wind. An extensive investigation involving multiple agencies and parties is underway. It will include interviews with the pilots on board and all bridge personnel and other crew members, a company spokesman said.

Meanwhile, the channel remains blocked and the latest reports from people familiar with the rescue efforts suggest it will take until at least Wednesday.

As a conduit for 12% of world trade, an average of 50 ships pass through Suez every day in convoys that leave early in the morning. The Ever Given began its journey shortly after sunrise and picked up two local pilots from the Suez Canal Authority. They come on board to supervise the ships that make the journey down the waterway, which can take up to 12 hours. But the authority’s rules of navigation clearly state that the master, shipowners and charterers remain liable for accidents.

The Ever Given captain overseeing the bridge had made the trip across the Suez many times before and had driven it in gusts of wind, according to a former crew member. Shipping companies say they use their top captains for Suez because of the delicate nature of the trip.

But what happened next left $ 10 billion worth of goods with nowhere to go with more than 300 ships carrying products across multiple industries now stuck in stagnation.

The Ever Given lost its course and began to turn to starboard about 5 miles at the mouth of the channel. The 200,000-ton ship then slid to the port side, and soon turned sideways and ran aground, her bulbous red bow protruding to efficiently cut through the water firmly embedded in the sandy embankment.

“We have a single ship here that is out of place and yet has an impact on the entire maritime and global economy,” said Ian Ralby, CEO of IR Consilium, a maritime law and safety consulting firm that works with the governments. “This ship, which carries exactly the kinds of things that we rely on on a day-to-day basis, shows that the supply chains that we rely on are so integrated and the margin for error is very small.”

Those who rebuild what caused the accident will undoubtedly look at speed. The ship’s last known speed was 13.5 knots at 7:28 a.m., 12 minutes before grounding, according to Bloomberg data.

That would have exceeded the speed limit of approximately 7.6 knots (8.7 miles per hour) to 8.6 knots that is listed as the maximum speed at which ships “can transit” through the canal, according to the manual. of navigation rules of the Suez authority published on its website. Captains interviewed for this story said that it can be profitable to increase speed in a strong wind to better maneuver the boat.

“Accelerating to a certain extent is effective,” said Chris Gillard, who was the captain of a 300-meter container ship that crossed the Suez monthly for nearly a decade until 2019. “More than that and it comes back against cash because the bow will make it be sucked deep into the water. So adding too much power only exacerbates the problem. ”

Bloomberg data also shows that the 300-meter Maersk Denver traveling behind Ever Given also posted a top speed of 10.6 knots at 7:28 a.m. A Maersk spokesperson in Denmark declined to comment. Boat captains and local pilots said it is not unusual to travel the canal at that speed despite the lower limit.

The Cosco Galaxy, a slightly smaller container ship than Ever Given, was immediately ahead and appears to have traveled at a similar speed, albeit with a tugboat. The one in front of the Cosco, the Al Nasriyah, also had an escort. Escorts are not mandatory, according to the Suez Authority’s navigation rules, although the authority may require it for ships if it deems it necessary.

“Larger ships often travel with a tugboat in close proximity, an escort ship, to facilitate transit,” said Captain Theologos Gampierakis of the commodity trading house Trafigura Group in Athens.

A high-stacked container cargo ship like the Ever Given can be particularly difficult to navigate, as the ship’s hull and container wall can act like a massive sail, said Kinsey, the former captain, who made his last voyage. through Suez in 2006.

“You may find yourself pointing the ship in one direction and actually moving in another direction,” Kinsey said. “There is a fine line between having enough speed to maneuver and not having too much speed for the air and hydrodynamics to become unstable. Any deviation can get really bad really fast because it’s so tight. ”

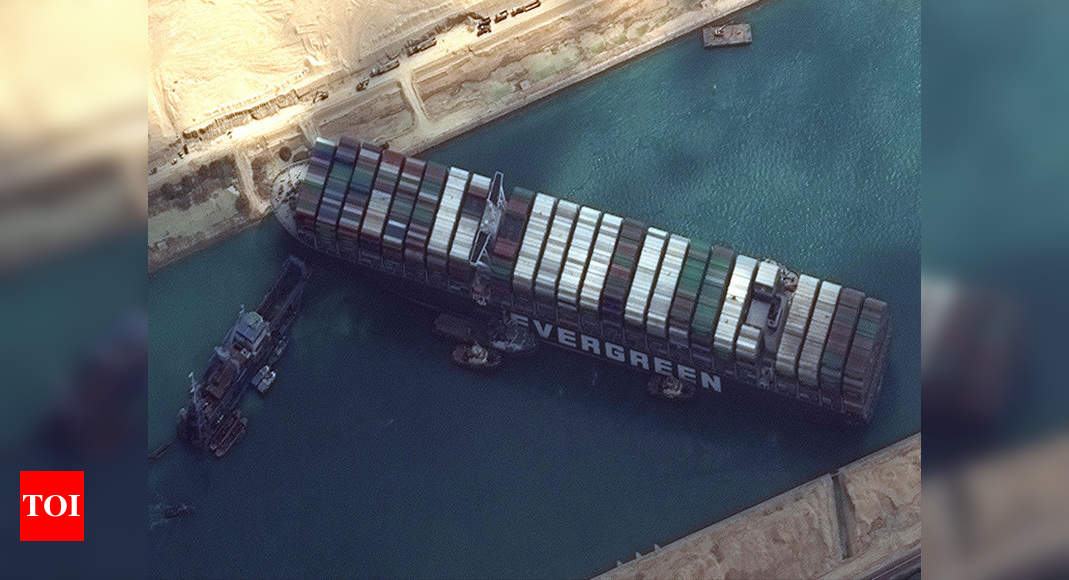

About 20 minutes after the incident, the first of the two tugs accompanying the ships ahead of Ever Given returned to push her port side in an effort to dislodge her, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Subsequently, eight tugs were deployed to push both sides of the container ship, but to no avail.

On land, officials and investigators were dispatched to the embankment. The excavators tried to chip away at it to help free it from the sandy embankment.

In a town 100 meters from the stuck ship, the ship looms over the horizon like a giant monument. Each day it sits still makes it harder to get it out, due to the sediment carried by the currents that build up around the boat underwater, Kinsey said.

The accident will be a missed opportunity if the industry doesn’t adapt, he said. “There will be larger vessels than this going through Suez,” he said. “The next incident will be worse.”

.