[ad_1]

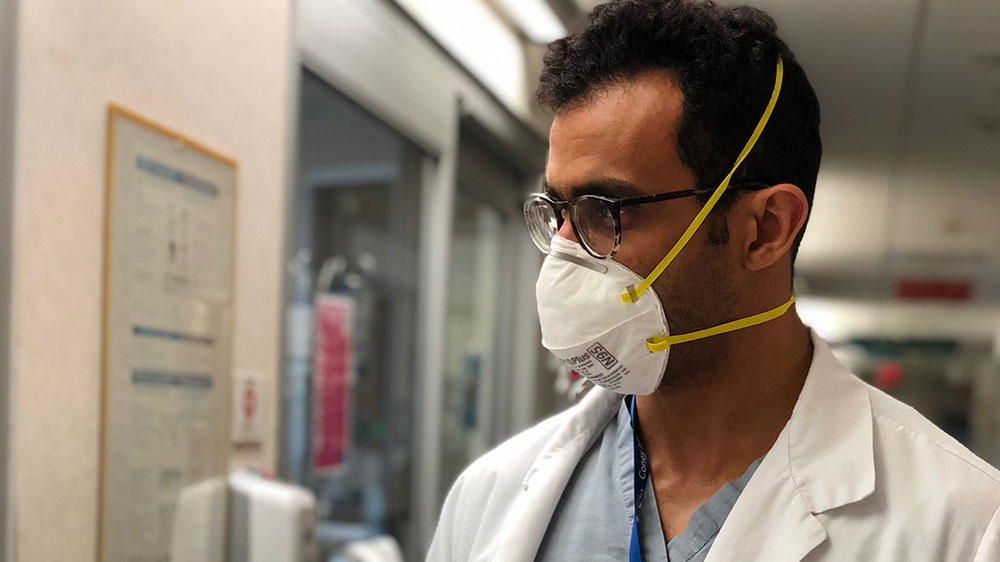

New York City – Dr Ahmed Hozain intends to wake up around 4am on Friday and begin the first day of his Ramadan fasting. For 15 hours, the 32-year-old surgery resident and lung transplant researcher plans to abstain from eating, drinking, chewing gum and taking medicine as he goes through his daily routine, which now includes caring for more than a dozen COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit at the Brooklyn hospital where he works.

More:

Hozain has been fasting since he was 10 years old, and although some days are harder than others, he generally feels good. He is a bit sharper mentally. He has more free time. He does not worry about feeling tired after a big meal. Even in his first years of practicing medicine, when he would sometimes be pulled unexpectedly into the emergency room and have to extend his fast for an additional hour or two, he never broke early and ate before sunset.

But amid the exhaustion of fighting a pandemic, he wonders whether that will be the case this year.

“The goal is to go through it like I’ve always done,” he says. “But, I’m not opposed to breaking it if I need to.”

Muslims worldwide are trying to figure out how they’ll adapt their religious practices to a radically different world during the holy month of Ramadan. In March, the National Muslim Task Force issued a statement that urged the United States’s more than 3.4 million Muslims to “follow local protocols for self-quarantine and social distancing” and requested that congregational prayers be suspended. Even in the 12 states with religious exemptions to their stay-at-home orders, mosques contacted by Al Jazeera have been closed for weeks, including those in Jacksonville and Gainesville, Florida, Dearborn, Michigan, Missoula, Montana, Birmingham, Alabama, and Austin, Texas.

“Anecdotally, I do not know of a single mosque in America that remains open for business right now,” says Edward Ahmed Mitchell, the executive director of the Council of American-Islamic Relations. “And the few that were kind of stragglers and delayed by a week or so – even they ended up getting on board.”

On one hand, these closures have severely disrupted the traditions surrounding Ramadan, when Muslims typically break their fast together as a community.

On the other, Islam is uniquely capable of adapting to the stay-at-home orders. Ramadan does not require Muslims to pray inside a mosque, and the dangers of a pandemic are part of the religion’s founding. “Historically, the Prophet Muhammad, may peace and blessings be upon him, taught people that if a plague breaks out in your land, don’t leave,” says Mitchell. “And if a plague breaks out somewhere else, don’t go there. So this wasn’t a major theological dispute.”

Due to the quarantine, many Muslims now control their daily schedules in a way that is normally impossible during the holy month. But the opposite is true for thousands of doctors, nurses and other essential workers in the US, who are overworked and under immense stress.

“Cognitively, you’re engaged the whole day,” says Hozain, whose patients have such trouble breathing that the majority must be intubated. “If I don’t give that patient sedation, they’re freaking out. They’re very uncomfortable. They’re biting on the tube,” he says. “So you have to give them enough medication that they don’t fight it, but not too much because it can have longer-term side effects.”

Pros and cons

Should Hozain want to delay his fast, the Quran allows him to make up the days at a later time.

“Islam teaches that protecting human life is the number-one priority,” says Mitchell. “So there are exceptions to almost every religious rule.”

However, religious authorities disagree about how widely these exemptions should be applied. “Fasting is uncomfortable,” says Kassem Allie, executive administrator for the Islamic Center of America, in Dearborn, “but you can’t just say, ‘I don’t feel well. I’m not going to fast.’ To really be excused from fasting, you need to have the recommendation from a physician. “

Others see the decision as more of a personal choice, like Adam Stadheim, an assistant imam at the University of Montana. He compares it to how you are permitted to sit during prayers if standing causes you pain. “How do you decide what’s too painful?” he asks. “Enough that it distracts you, so there is a level of subjectivity in determining if you feel too sick.”

But those who choose not to fast miss out on a fundamental part of Islamic culture, says Shima Dowla Anwar, a 31-year-old MD / PhD candidate in Birmingham with a stomach condition that typically prevents her from fasting for more than a few days at a time.

“It’s a communal experience,” she says. “Everybody’s talking about it. Everybody’s going through it together, and I don’t get to do that with them.”

Echoing that sentiment is Dr Bedirhan Tarhan, a 31-year-old resident in pediatric neurology in Gainesville, Florida. Though he loves fasting, he is uncertain whether he will go the full month should the number of cases spike in his area. “If I feel like the fast is affecting my health or performance fighting against the virus, I’ll delay it,” he says.

For other doctors, though, there is no doubt. Despite the fact that Dr Mobeen Rathore’s models predict the virus to peak around the second week of Ramadan in the Jacksonville area, the infectious disease specialist, who has been practicing for almost 29 years, says it has “never even been a consideration not to fast “

For Hozain, not fasting is a consideration, but not an easy one, especially in the heat of the moment.

“I’ve always wondered, ‘Am I actually judging myself fairly to be able to determine my capacity to work, or is it an unfair, biased judgment?’,” He says.

However, he trusts the other doctors to help him make the decision, and after more than 20 years of observing Ramadan, he also trusts himself. “You know yourself,” he says, “and you know how hard you work, and you know how sharp you need to be and what kinds of clinical decisions you need to make.”

[ad_2]

![Dr Ahmed Hozain who is on the coronavirus front lines says he plans to fast this year [Courtesy of Dr Ahmed Hozain] Muslim doctors - US](https://news.google.com/mritems/Images/2020/4/23/9fa0f4fd65254cbd9e6beb4b42e7feb4_18.jpg)

![A student studying medicine helps a patient in a Detroit hospital [File: Rebecca Cook/Reuters] Muslim doctors](https://news.google.com/mritems/Images/2020/4/23/db3da1e47fed4ffb90ed08d0f1eed939_18.jpg)

![A doctor uses his phone outside the emergency center at Maimonides Medical Center during the outbreak of the coronavirus in the Brooklyn borough of New York [Brendan McDermid/Reuters] NYC doctor](https://news.google.com/mritems/Images/2020/4/23/96013a43b0254f75a53f1cee3c09c4d1_18.jpg)

![Healthcare professionals prepare to screen people for the coronavirus at a testing site erected by the Maryland National Guard in a parking lot at FedEx Field March 30, 2020 in Landover, Maryland [Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images/AFP] US hospitals](https://news.google.com/mritems/Images/2020/4/3/1270058293b84435a80b05c909a12cb0_18.jpg)