[ad_1]

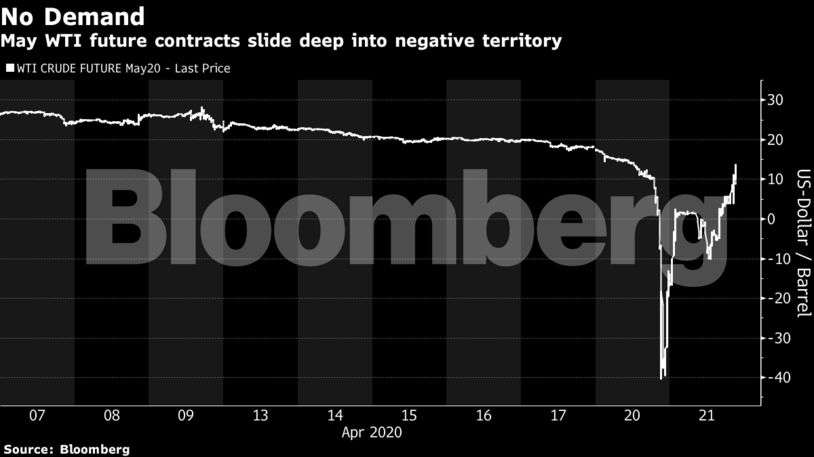

Frantic sell orders had been arriving overnight, and any merchant connecting to the Nymex platform that morning could see a bloodbath coming. At 7 am. in New York, the price of a key futures contract – West Texas Intermediate for May delivery – was already down 28% to $ 13.07 a barrel.

Thousands of kilometers away, in the Chinese metropolis of Shenzhen, a 26-year-old girl named A’Xiang Chen watched the events unfolding on her phone in amazement and disbelief. A few weeks earlier, she and her boyfriend had plunged all of their around $ 10,000 money into a product the state Bank of China called Yuan You Bao, or Crude Oil Treasury.

As the night wore on, A’Xiang began preparing to lose everything. At 10 pm. in Shenzhen at 10 a.m. In New York, he checked his phone one last time before going to bed. The price was now $ 11. Half of his savings had been eliminated.

While the couple slept, the defeat deepened. The price set a new low after a new low in rapid-fire succession: the lowest since the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, the lowest since the oil crises of the 1970s, the first time below zero .

And then, in a span of 20 minutes that ranks among the most extraordinary in the history of financial markets, the price dropped to a level few, if any, believed conceivable. Around the world, Saudi princes and wild Texas hunters and Russian oligarchs watched in horror as the world’s top product closed trading day at a price of less than $ 37.63. That’s what you would have to pay someone to take the barrel out of your hands.

Many things about the explosive nature of the sell-off are still not fully understood, including the huge role the Treasury fund played in crude oil trying to pull out of the May contracts hours before expiration (and that other investors were found in the same position). What is clear, however, is that the day marked the culmination of the most devastating oil market crisis in a generation, the result of declining demand as governments around the world blocked their economies in an attempt to manage the coronavirus pandemic.

For the oil industry, it was a grim and symbolic moment: the fossil fuel that helped build the modern world, so prized that it became known as “black gold,” was now not an asset but a liability.

“It was amazing,” said Keith Kelly, managing director of the energy group at Compagnie Financiere Tradition SA, a leading broker. “Are you seeing what you think you are seeing? Are your eyes deceiving you?

U.S. ETF pain

While the deeply negative prices on that Monday were largely limited to the US. In the US, and in particular the WTI contract that will soon expire for the May delivery, the world felt the shock waves, with blast wave effects dragging global prices to the lowest since the late 1990s.

Traders are still rebuilding the confluence of factors that led to the collapse. And regulators are analyzing the issue, according to people familiar with the matter.

However, for small Asian investors like A’Xiang who enthusiastically bet on oil, it has been a calculation.

Woke up to a text message at 6 a.m. from the Bank of China informing her that not only had her savings been lost, but she and her boyfriend might actually owe money.

“When we saw the price of oil start to drop, we were prepared for all our money to disappear,” he said. They had not understood, he said, what they were getting into. “It didn’t occur to us that we had to pay attention to the futures price abroad and the full concept of the contract.”

In total, there were some 3,700 retail investors in the Bank of China Crude Treasury Fund. Collectively, they lost $ 85 million.

Soon, events would catch up with American investors who had made the same bet as A’Xiang, that oil had to go back up, buying the United States Petroleum Fund, a publicly traded fund known as USO .

That fund, in which investors invested $ 1.6 billion the previous week, had not entered into the May WTI contract on Monday. But the defeat sparked a chain reaction in the market that also burned these investors.

Bloomberg

The events of the day were launched more than two weeks before, with the pandemic that destroyed the economies and stalled the demand for oil: the flights were on the ground; traffic jams disappeared; factories stopped.

The scenario of sub-zero prices was, in some corners of the market, beginning to be considered. On April 8, a Wednesday, CME Group Inc, which owns the oil futures exchange, informed customers that it was “ready to handle the negative underlying price situation in major energy contracts.”

That weekend, producer nations led by Saudi Arabia and Russia finalized their response to the crisis: an agreement to cut production by 9.7 million barrels per day, equivalent to one-tenth of world production. That would not be enough. Refineries began to close. Buyers of oil shipments for immediate delivery to physical markets have disappeared.

Futures prices were, for a time, relatively stable.

That was in part thanks to people like A’Xiang. In China, big and small investors were betting on higher commodity prices, believing that the world would overcome the virus and that demand would pick up. Bank of China branches posted ads on Wechat, showing a picture of golden barrels of oil titled “Crude oil is cheaper than water.”

However, on April 15, CME offered customers the ability to test their systems to prepare for negativity. It was then that the market really woke up to the idea that this could really happen, said Clay Davis, director of Verano Energy Trading LP in Houston.

“It was then that the dam broke,” he said.

Physical delivery

By the time Monday, April 20 arrived, most ETFs and other investment products, though not the Crude Oil Treasury fund, had changed their position from the May WTI contract to next month.

Futures contracts are settled by physical delivery, and if you get stuck with one when it expires, you become the owner of 1,000 barrels of crude. It’s rarely about that.

But now it was.

The physical agreement for the WTI landmark takes place in Cushing, Oklahoma. When the storage tanks are full, the expiring contract price may drop and disconnect from the global market. With the evaporation of demand, inventories in Cushing soared. In March and April, they rose 60% to just under 60 million barrels, out of a total working capacity of 76 million, and analysts estimate that much of the remaining space has already been allocated.

So on crucial Monday, the penultimate day of trading in the May WTI contract, there were very few merchants able or willing to receive physical delivery.

Much of the market then focused on the settlement price, determined at 2:30 p.m. In New York. Investment products, including those of the Bank of China, generally seek to achieve the settlement price. That often involves so-called settlement time trading contracts, which allow oil traders to buy or sell contracts in advance for any settlement price.

No buyers

On that afternoon, with reduced trading volumes and sellers outnumbering buyers, settlement trading contracts quickly moved to the maximum allowable discount of 10 cents a barrel. For a period of about an hour, from 1:12 p.m. As of 2:17 p.m., trading on these contracts sold out. There were no buyers.

The result was the butcher shop that afternoon. At 2:08 p.m., WTI turned negative. And then, minutes later, it sank below $ 40.32 before recovering slightly at the close.

“The settlement trading mechanism failed,” said David Greenberg, president of Sterling Commodities and a former board member of Nymex. “It shows the fragility of the WTI market, which is not as big as people think.”

Prices in the US physical market. Set in reference to the WTI deal, the US also plummeted, with some refineries and pipeline companies posting prices to their suppliers as low as minus $ 54 per barrel.

The Bank of China investment product offers an explanation for why the move below zero was so dangerous. The bank had required investors like A’Xiang to prepay the full cost of what they were buying. That meant that the bank’s position seemed risk-free.

But not if prices fell below zero – then there wouldn’t be enough money in investor accounts to cover the losses.

The bank had a total position of about 1.4 million barrels of oil, or 1,400 contracts, according to a person familiar with the matter. He ended up having to pay about 400 million yuan ($ 56 million) to settle the contracts.

Across the investment world, others faced similar risks. ETFs could go bankrupt if the price of the contracts they held was below zero. Given this possibility, they moved a large part of the stocks to the last months of delivery. Some brokers prevented clients from opening new positions in the June contract.

The movements amounted to a new wave of sales that spread through the oil markets. On Tuesday, the June WTI contract fell 68% to a low of just $ 6.50. And this time it was not limited to EE contracts. US: Brent futures also plummeted, hitting a 20-year low of $ 15.98 on Wednesday, bringing the price of Russian, Middle Eastern, and West African oil to a price close to zero.

CFTC’s Top Priority

Harold Hamm, president of Continental Resources Inc., called for an investigation, saying the dramatic drop in the final minutes of Monday “strongly raises suspicion of market tampering or a defective new computer model.”

According to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, unpacking what happened during those final trading minutes on April 20 has become a top priority, according to people familiar with the matter. While reviews and investigations into what has just started are, so far, senior officials believe the moves were likely the result of a confluence of market and economic factors, rather than the result of market manipulation.

One problem CFTC is exploring is whether the storage capacity data released by the US Energy Information Administration. USA They accurately reflect the actual availability of space, two of the people said.

“The temporarily negative price at which the WTI Crude futures contract was traded earlier this week appears to be rooted in fundamental supply and demand challenges along with the particular characteristics of that futures product,” said CFTC President Heath Tarbert. to Bloomberg News.

However, he added: “CFTC is taking a deep dive to understand why the WTI price moved with the observed speed and magnitude, and we will continue to monitor the role of our markets to facilitate convergence between spot and futures prices to maturity.” .

The CME, for its part, argues that Monday’s decline was a demonstration that the market works efficiently. “The markets functioned exactly as they are supposed to,” CEO Terry Duffy told CNBC. “If Hamm or any other commercial believes that the price should be above zero, why wouldn’t they have stopped there and taken every barrel of oil if it were worth anything more? The real answer is that it was not at that moment. ”

Who is right, the events of the week have changed the oil market forever.

“We witnessed the story,” said Tamas Varga, an analyst at the PVM brokerage. “For the sake of oil market stability,” this “should not be allowed to happen again.”

[ad_2]