Updated: December 17, 2020 8:50:03 am

The stagnation in stunting rates is particularly alarming. Height, unlike weight, is not affected by short-term factors, so it is not a temporary setback. Stunting in childhood is associated with serious deficiencies later in life, including lower school achievement.

The stagnation in stunting rates is particularly alarming. Height, unlike weight, is not affected by short-term factors, so it is not a temporary setback. Stunting in childhood is associated with serious deficiencies later in life, including lower school achievement.

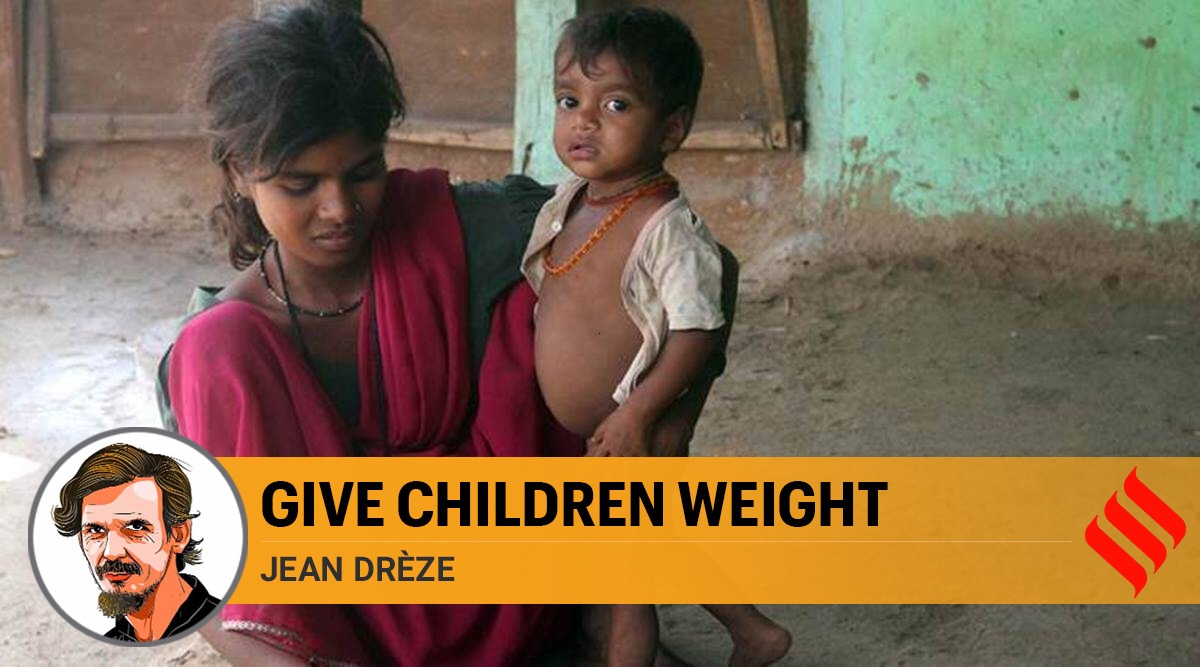

Leaving aside two or three countries like Niger and Yemen, India has the highest proportion of underweight children in the world – 36 percent according to the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4). The corresponding share is much lower in other South Asian countries, including Bangladesh (22%) and Nepal (27%). If we focus on childhood stunting (short height for age) rather than low weight for age, India’s ranking improves somewhat, but it still stands out as one of the most malnourished countries, accompanied by a dozen other countries. like Ethiopia, Congo and Afghanistan. These alarming facts, based on the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, are rarely discussed in India’s long-winded democracy.

The first data from the National Family Health Survey 2019-20 (NFHS-5), published a few days ago by the Minister of Health, reveal another alarming fact: child nutrition indicators have not improved between 2015-16 and 2019-20 . In fact, in seven of the top 10 states for which data has been published, the proportion of underweight children increased in that period. In six of these 10 states, stunting increased.

The proportion of malnourished children in these 10 states combined (about half of the population of India) can be estimated with reasonable precision as a population-weighted average of the state figures. This equates to 36 percent for stunting and 34 percent for underweight, the same, in both cases, as the corresponding weighted average for 2015-16, based on data from the NFHS-4. This suggests that the progress of infant nutrition in India, modest as it was before, has stalled.

The stagnation in stunting rates is particularly alarming. Height, unlike weight, is not affected by short-term factors, so it is not a temporary setback. Stunting in childhood is associated with serious impairments later in life, including lower school achievement.

Note that the NFHS-5 data refers to the situation just before the COVID-19 crisis. A year later, child nutrition is likely to have deteriorated. In fact, numerous household surveys point to severe food insecurity in India in 2020. In the latest survey, Hunger Watch, two-thirds of respondents (adults from the poorest households in India) said they were eating less nutritious food today than before closing. a chilling thought. It would be surprising if this did not have an adverse impact on child growth.

To a large extent, the noon meals in the schools and anganwadis were discontinued from closure onward, until today. Many states tried to make some arrangement for the distribution of cash or “take-home rations” instead of cooked meals, but these measures were mostly careless and inadequate. Children have also suffered massive disruption to routine health services, including immunization, during the shutdown, as evidenced by the official Health Management Information System. The Anganwadis, for their part, have been closed for almost a year in most parts of the country. The prolonged closure of anganwadis and schools possibly had other less documented consequences, such as an increase in child labor and child abuse. In short, 2020 was a general catastrophe for Indian children.

All of this requires urgent intervention. The first step is to value children’s development, both for their own sake and for the future of the country. On this, the NDA government has a lot to answer for. In its first annual budget, for 2015-16, there were staggering cuts in financial allocations for midday meals and Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), far more than could be justified on the grounds that states were getting a higher share of the tax fund. The cuts were partially reversed later in the year, but to this day, the core budget for midday meals (Rs 11,000 crore) is lower than in 2014-15 (Rs 13,000 crore). In real terms, the core allocation for ICDS is also lower today than it was six years ago. Poshan Abhiyaan, the NDA government’s flagship program for child nutrition, has a miniscule budget of Rs 3.7 billion.

For several years, the NDA government also failed to respect the right of pregnant women to maternity benefits: 6,000 rupees per child under the National Food Safety Act of 2013. When it finally launched a plan (Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana ) to this end, in 2017, benefits were illegally restricted to one child per family and 5,000 rupees per child. In many states, NDA allies and associates also have a distinguished record of opposing or resisting the inclusion of eggs in midday meals and take-home rations – one of the best things to do without delay. to improve child nutrition.

The next Budget, for 2021-22, is an opportunity to compensate for some of these lapses. Ad hoc measures will not be enough, we need bold and lasting initiatives. Reviving and renewing the midday meals in schools and anganwadis would be a good start. Eggs are asking to be included as a matter of national policy (not just in midday meals but also in take-home rations for young children and pregnant women), with a choice of fruit or similar for vegetarians. Extending maternity rights to all births, not just the first living child, is a legal obligation under the NFSA, and the spirit of the law also calls for increasing its amount well above the outdated rule of Rs 6,000 per child. .

The ICDS program also requires an injection in the arm. India has an invaluable network of 14 lakh Anganwadis run by local women. Most of these anganwadi workers and helpers are capable women who can work wonders in a supportive environment. The southern states, and some other states such as Himachal Pradesh and even Odisha, have amply demonstrated the possibility of turning the Anganwadis into vibrant village-level child development centers. There is no better way to reach the young children of the country.

These are just a few examples of possible initiatives. However, none of this is likely to happen without some introspection about political priorities. If India’s overwhelming goal is to become a $ 5 trillion economy in a few years, there is no reason to pay attention to children. But if it is about development in the full sense of the term, then child development is paramount.

This article first appeared in print on December 17, 2020 under the title ‘Give Weight to Children’. The author is a visiting professor in the Department of Economics at Ranchi University.

.