[ad_1]

“Look at London, talk to Tokyo” is an expression that is sometimes used to describe a wink or a squint. But this could literally be a fitting metaphor for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Rs 20-lakh-crore stimulus announced to revive India’s economy affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Behind Modi’s obvious drive for self-sufficiency in India through a so-called “Atma Nirbhar Bharat”, there is no conventional inward approach that was the hallmark of Mahatma Gandhi’s Swadeshi approach that advocated a “Be Indian” philosophy. , buy Indian “, nor is there a Nehruvian desire to get out of the clutches of the colonial era by building a national industrial base.

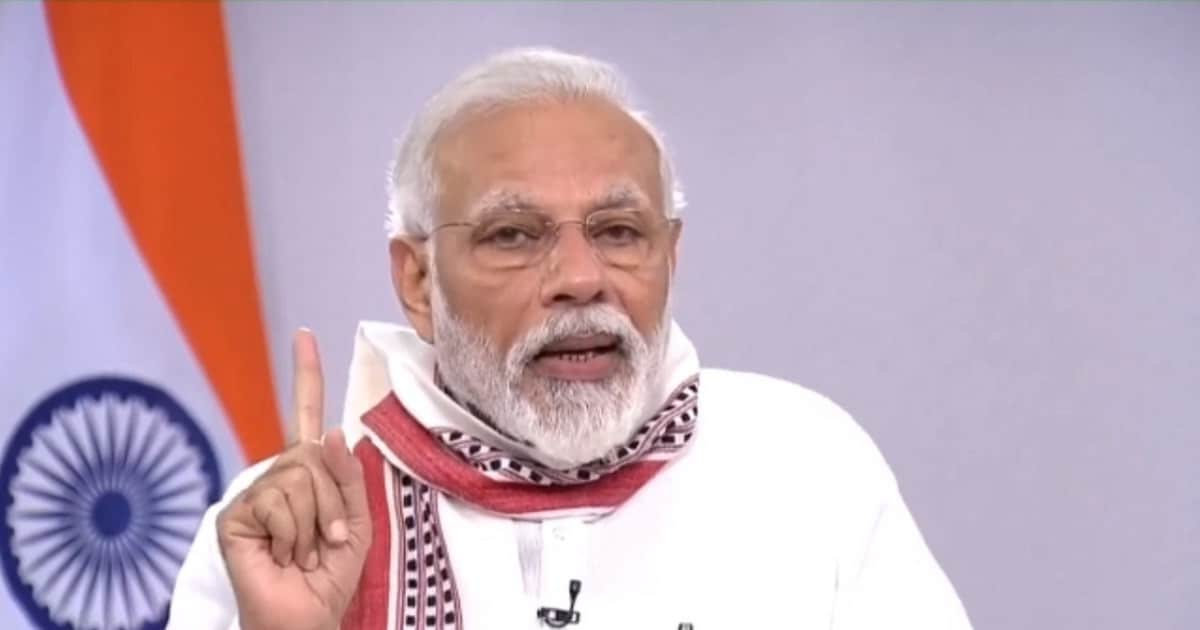

Prime Minister Narendra Modi. AND ME

While what we see externally is a cocktail of the two in terms of political messages to build on national pride, the deepest subtext is from a post-globalization and post-Coronavirus universe in which India is trying to reduce imports from China as it becomes an alternative manufacturing base in a global web supply chain. A key conclusion of Modi’s speech is: “India does not advocate self-centered arrangements when it comes to self-reliance.”

Many questions remain to be answered, as the details of the prime minister’s package have yet to be finalized. The planned announcements by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will be closely watched.

But it is clear that to really gain the importance of Modi’s strategy, we have to look beyond his loyal cheerleaders who see great political skill in everything he does or says, and his bitter critics who quickly find fault or superficiality in what he says. what does it say.

We have to look at both the content and the context of Modi’s 33-minute speech to get some clarity. They are such that he is trying to group the inevitable as an initiative while detecting the opportunity in the threat of the virus that could alter the world economic order. We could call it the emergence of “geoeconomics” as a logical corollary of geopolitics in which Japan and the West can seek an alternative growth base to crowned China. India is clearly the leading large-scale candidate to fill the gap.

But there are many slips between the cup and the lip. Questions remain about the key aspects of the stimulus, including land and labor issues that go beyond the simple arithmetic formula of spending to drive growth.

First, we need to know what short-term aid is needed on a large scale to help hundreds of millions of migrant and informal sector workers cope with a lack of jobs / income on the one hand and a public health emergency on the one hand. other . As this is being written, crowded train stations and migrants walking on the roads represent a clear and present danger of a community spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, we need to see how much of the stimulus package constitutes real spending involving taxpayer money. It is clear that what India lacks now is demand and a tax restriction at the moment does not seem desirable or feasible. If global credit rating agencies see a financial crisis stemming from overspending, it can put foreign direct investment (FDI) in difficult terrain. However, industrial production declined 16.7 percent year-on-year in March, when the blockade began. Modi was correctly misguided on the side of industrial recovery rather than inflation management because four-month lows retail inflation provides the right drag to spend more. Lower world oil prices also provide a margin for spending.

It is unclear whether the movements of the Reserve Bank of India to help liquidity are part of the planned stimulus. We can reasonably assume that credit guarantees to help small businesses can generously increase the stimulus number that looks like 10 percent of GDP, but it will indeed be a lesser fiscal threat to the government. The speech aims to talk about a frozen economy, which is smart because things have reached a point where the threat of hunger, unemployment and social chaos seem to be bigger than Wuhan’s invisible virus.

That still leaves us with the big question: where will the extra dose of money come from? A smart guess would be: abroad. While global investors with their point of view from London or New York may consider India as a long-term alternative to China, the close relations of the Modi government itself with Japan may provide influence. Japan has announced a $ 1.1 trillion stimulus to meet the COVID-19 challenge, estimated at 21 percent of Japan’s GDP. Some of that money may go to India because India has a manufacturing base and demographic equation plus demand that provides a market for a developed country in search of a market. Modi spoke clearly of demographics and demand factors in his speech. Remember, India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar is an old hand from Japan.

We also have to consider the labor law liberalization measures in the BJP-ruled states in recent days, especially in Uttar Pradesh, as an incentive for Japanese investors because infrastructure and labor issues have been critical to Samurai corporations.

The investment, however, is only part of the future story. Migrant workers returning to their villages, and their psychological nursing injuries caused by an unimaginable virus threat, will be considered to bring them back to their workshops, or not. If controversial labor laws hinder your mood instead of helping you, things could be difficult. Last but not least, even if foreign manufacturers increase their base in India, it will take some time to establish a store, and when they do, given the growth of robotics and automation in all industries, we don’t know how long that translates into jobs for millions of people.

However, if the stimulus is used to clean up India’s banking system through measures such as a widely speculated “bad bank” to absorb the hangover from the Unprofitable Assets (NPA) problem, public sector banks can revive or facilitate loans to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). That could help more than FDI injections in job creation.

We also need to see the timeline on which the government will spend its money and how industries respond. The COVID-19 threat is a health scare. Some of the behavioral changes you have introduced and / or will introduce are unknown factors in a complex economic chessboard. One is tempted to draw a parallel with Modi’s 2016 gambit on the demonetization of high-value banknotes that didn’t quite work. With an estimated 27 to 30 million young people who lost their jobs in April (which is more than the population of all of Australia), the big threat to any fiscal boost is not inflation but unemployment, for which there is no panacea.

Modi’s speech is therefore a long-term strategic boost and a short-term mood builder. Between the mood and the promise falls the long shadow of the real-life economy.

Just as hydroxychloroquine is more of a tentative treatment for the COVID-19 virus than a certain cure, boosting Modi may be more necessary, but not a gambit enough to boost India’s economy.

The writer is a journalist and lead commentator. Tweet as @madversity

.

[ad_2]