[ad_1]

(MENAFN – The Conversation) Scientists recently confirmed that the Great Barrier Reef suffered another serious bleaching event last summer, the third in five years. Dramatic intervention is clearly needed to save the natural wonder.

First of all, this requires reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. But the right mix of technological and biological interventions, deployed carefully at the right time and scale, are also critical to securing the future of the reef.

Read more: We just spent two weeks inspecting the Great Barrier Reef. What we saw was a total tragedy.

This could include methods designed to shade and cool the reef, techniques to help corals adapt to warmer temperatures, ways to help damaged reefs recover, and smart systems that direct interventions to strategically most beneficial locations.

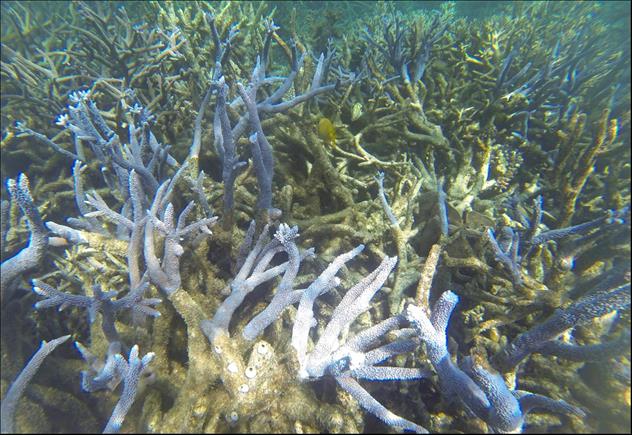

Research on breeding coral hybrids for resistance to heat stress could help restore parts of the reef. Marie Roman / AIMS, provided author

Implementing such measures across the reef, the world’s largest reef ecosystem, will not be easy or cheap. In fact, we believe that the scale of the task is larger than the Apollo 11 moon landing mission in 1969, but not impossible.

That mission was successful, not because some elements worked to plan, but because of the integration, coordination, and alignment of each element of the mission objective: to be the first to land and walk on the Moon, and then fly home safely.

Half a century later, in the face of the continuing decline of the Great Barrier Reef, we can draw important lessons from that historic human achievement.

Intervene to save the reef

The recent feasibility study of the Reef Adaptation and Restoration Program concept shows that Australia could, feasibly, and with a reasonable probability of success, intervene to help the reef adapt and recover from the effects of climate change.

The study, of which we are a part, involved more than 100 scientists, modelers, economists, engineers, business strategists, social scientists, decision scientists, and coral reef managers.

More than 100 coral reef scientists participated in the feasibility study. Nick Thake / AIMS, provided author

It shows how new and existing interventions, backed by the best research and development available, could help secure a future for the reef.

We must emphasize that interventions to help the reef adapt and recover from climate change alone will not save it. Success also depends on reducing global greenhouse emissions as quickly as possible. But the practical steps we propose could help save time for the reef.

Cloud shine to heat tolerant corals

Our study identified 160 possible interventions that could help revive the reef and take advantage of its natural resilience. We have reduced it to the 43 most effective and realistic.

Possible interventions for further research and development include bright clouds with salt crystals to shade and cool corals; ways to increase the abundance of naturally heat-tolerant corals in local populations, such as through selective breeding and aquarium-based release; and methods to promote faster recovery on damaged reefs, such as the deployment of structures designed to stabilize reef debris.

But there will be no single silver bullet solution. The feasibility study showed that methods that work in combination, along with improving water quality and controlling crown-of-thorns starfish, will provide the best results.

Field test of heat-resistant coral hybrids on the Great Barrier Reef. Kate Green / AIMS, author provided Harder than landing on the moon

There are four reasons why saving the Great Barrier Reef in the coming decades could be more challenging than the 1969 Luna mission.

First, warm-up events have already driven the reef into decline with consecutive bleaching events in 2016 and 2017, and now again in 2020. The next major event is now just around the corner.

Read more: ‘This situation drives me to despair’: two reef scientists share their climate pain

Second, current emissions reduction promises would see the world warm by [2.3-3.5℃ relative to pre-industrial levels][https://www.nature.com/articles/nature18307]. This climate scenario, which is not the worst case scenario, would be beyond the range that allows current coral reef ecosystems to function.

Without swift action, the outlook for the world’s coral reefs is bleak, and most are expected to seriously degrade before the middle of the century.

The Great Barrier Reef has been hit by successive bleaching events; Restoring it can be more difficult than landing on the moon. Shutterstock

Third, we still have work to do to control local pressures, including water quality and marine pests of crown-of-thorns starfish.

And fourth, the inherent complexity of natural systems, particularly those as diverse as coral reefs, offers an additional challenge that NASA engineers did not face 50 years ago.

Thus, keeping the Great Barrier Reef, let alone the rest of the world’s reefs, safe from climate change will outshine the challenge of any space mission. But there is hope.

We must start now

The federal government recently re-announced A $ 100 million from the Reef Trust Partnership for a major research and development effort for this program. This will be increased with contributions of A $ 50 million from research institutions and additional funds from international philanthropists.

Our study shows that, under a wide range of future emission scenarios, the program is very likely to be worthwhile, even more so if the world meets the Paris target and rapidly reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Read more: I studied what happens to reef fish after coral bleaching. What I saw still makes me nauseous

Furthermore, the economic analyzes included in the feasibility study show that the successful intervention of the Great Barrier Reef at scale could generate benefits for Australia of between A $ 11 billion and A $ 773 billion over a period of 60 years, and much of it will flow to regional economies and to traditional Owner communities

And perhaps most importantly, if Australia succeeds in this effort, we can lead the world in a global effort to save these natural wonders that have been handed down to us over the centuries. We must begin the journey now. If we wait, it may be too late.

The authors appreciate the contribution of David Wachenfeld, chief scientist of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and member of the steering committee for the development of this program.

MENAFN2304202001990000ID1100074874

[ad_2]