Updated: September 27, 2020 8:01:30 am

Farmers shout slogans as they block a train track in protest against new agricultural laws, in the village of Devi Dass Pura, about 20 kilometers from Amritsar (AP)

Farmers shout slogans as they block a train track in protest against new agricultural laws, in the village of Devi Dass Pura, about 20 kilometers from Amritsar (AP)

Dear readers,

Looking back, this week saw the debate over the agricultural sector reforms, just like him protest against that, intensify.

Although everyone accepts that most states have already liberalized the way mandis work, and that most agricultural trade is already happening in the private sector, protesters continue to demand that the government establish a law that no one can buy agricultural products unless the so-called Minimum Support Prices (MSP) that are announced by the government.

This is strange and unfortunate.

Funny because if the problems of the Indian agricultural sector could simply be solved by the government decree that no one would buy anything for less than the MSP, then the Indian agricultural sector would not have been as unprofitable as it is. A piece explained by looking at the agricultural sector data brought out what ails Indian agriculture.

Asking for an MSP guarantee to become law is the same approach as asking the government to cap all drug prices (ExplainSpeaking has written about this in the past) or ask the government to order everyone by law to pay high minimum wages, etc.

Of course, governments are expected to intervene when there is extreme distress. But, if all the problems in the Indian economy could be solved by the government by intervening in all markets and arbitrarily setting prices, then any government would have done it in one day and everyone would have been happy.

Politicians often use this delusional but obviously wrong thinking to win votes. For example, they can tell farmers that MSPs will increase by 50% while also promising consumers that food prices will be reduced by 50%. And while such promises are being made, they may also be telling market watchers that government deficits will shrink even as they tell taxpayers that relief is on the way.

This approach can be sustained because, for example, consumers never stop to wonder how food inflation will drop by 50% when MSPs to farmers increase by 50%. The same applies to farmers, and so on.

But the truth is, there are tradeoffs in any policy choice. Higher MSPs will result in more expensive food or higher subsidies and larger government budget deficits (and higher inflation) or higher taxes (to make up for the deficit), etc.

The unfortunate thing is that in the current political fight little attention is being paid to what will likely be the most important political factors in deciding whether or not farmers would be better off going forward.

Don’t miss Explained | Why Shiromani Akali Dal Separated From BJP Over 2020 Farm Bills

Three of those factors come to mind.

One is the need to ensure that the government allows farmers to benefit from the free play of markets. In other words, when prices go up, let farmers benefit from it rather than, say, arbitrarily imposing an export ban or allowing cheaper imports to cushion the blow to consumers.

Two, the need to create a support infrastructure that allows farmers to avoid making emergency sales. Proper and efficient storage can be a game changer.

Farmers shout slogans as they travel by tractors to New Delhi in Noida (AP)

Farmers shout slogans as they travel by tractors to New Delhi in Noida (AP)

Three, not to allow more free play on the market to degenerate into an exploitative and unregulated regime. That there are structures that provide a timely regulation of trade outside the mandi and allow effective mechanisms for the redress of claims.

These factors, rather than requiring a general unfeasible MSP guarantee, will be more influential now that these reforms have been put in place.

Aside from the farm bills, the other big story was the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in favor of Vodafone at Rs 22,100-crore. tax dispute (retrospective). Retroactive taxation, initially initiated under the AUP regime, has seriously damaged the credibility of India’s fiscal policy. If the government does not appeal, it would have to pay Rs 85 million to the company and the court.

The third big story was that of the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), among other embarrassing reports, finding that in the first two years of GST implementation, the Center incorrectly retained GST compensation process It was specifically intended to be used to compensate the states for lost income. The Union Ministry of Finance has responded to the CAG’s findings.

Looking ahead, the biggest issue of concern will be the RBI’s monetary policy review, which is expected on October 1. Before that, possibly sometime on Sunday, it is expected that the names of the three new members of the government-appointed Monetary Policy Committee will be announced.

Read also | He explained: In three ordinances, the provisions that annoy protesting farmers

There are three key issues to consider.

One, what will be the estimate of annual GDP growth that the RBI will publish?

With each passing month, all professional forecasters have had a worse level of contraction for the current year. The last was the National Council for Applied Economic Research, which said it does not see GDP growth in any of the last three quarters of this year. However, the rate of GDP contraction is expected to slow —24% in the first quarter up to —12.7% (in the second quarter), —8.6% (third quarter) and —6.2% (fourth quarter).

Two, what will the RBI’s inflation estimate be?

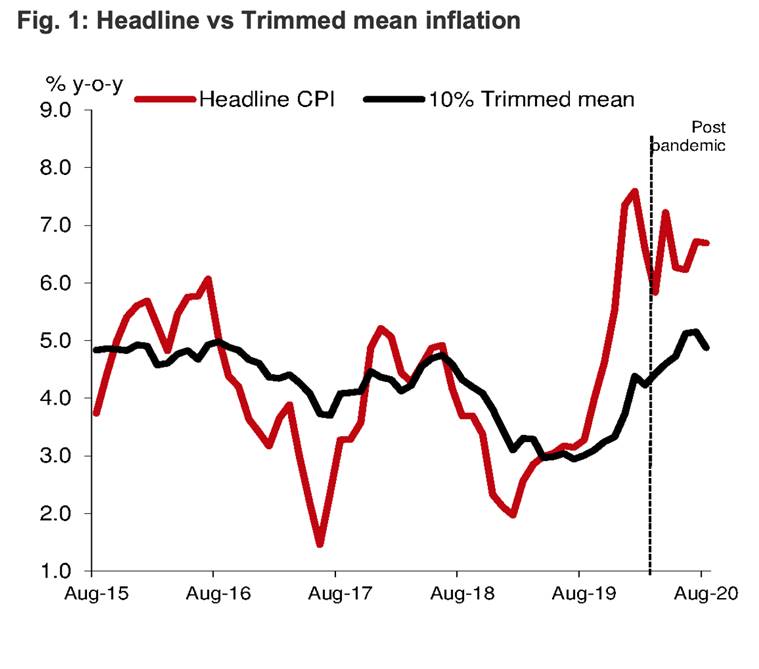

For most of the past year, retail inflation (which is what the RBI is targeting) has been above the central bank’s comfort band. The red line in the chart below (Source: Nomura) has just shot up and stayed well above the 4% mark pointed by the RBI.

At first glance, it can be argued that the second half of this financial year will see inflation moderated mainly by the base effect. In other words, given that prices spiked quite quickly in the second half of the last financial year, this year’s price increase may seem relatively less pronounced in comparison, and thus a lower inflation rate.

Source: Nomura

Source: Nomura

Some economists, like Nomura’s Sonal Varma, also point out that core inflation is much more benign than the headline figures suggest. The black line in the graph represents the 10% trimmed mean. In other words, it excludes 10% of each of the inflation components from the highest and lowest CPI for each month and, therefore, captures the trend in the most stable 80% of the basket.

The black line is substantially lower than the red one. It means that prices are not high across the board and some staples, like food, may be overstating the rate of inflation. This exaggeration is crucial because it could mislead legislators into thinking that inflation is quite high and therefore they should not cut interest rates, when in fact it is not, and there is room to cut rates further of interest.

However, the more important question for the RBI is to decide whether the current high inflation is just a “transitory” phenomenon, due to the pandemic, or is there a possibility that such high prices over a sustained period have started to make people “wait” that high inflation is here to stay more “permanently”.

📣 Express explained is now in Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay updated with the latest

In monetary policy calculations, these “expectations” about inflation are often more relevant than actual inflation. This is because consumer behavior, that is, their decision of whether they have enough income or what to do with it (spend more or save money), etc., often depends more on what they “expect” the rate to be inflation over the next three months. to 12 months.

Finally, everyone would be interested in whether the RBI decides to cut interest rates or not.

The broader consensus is that the RBI is unlikely to do so, mainly because it is most concerned about high inflation today, although GDP growth is the most “permanent” concern.

Stay safe

Udit

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay up to date with the latest headlines

For the latest news explained, download the Indian Express app.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd

.