September 20, 2020 8:42:58 am

Farmers protest in Patiala (Express photo by Harmeet Sodhi)

Farmers protest in Patiala (Express photo by Harmeet Sodhi)

Dear readers,

There was no shortage of trigger news for the economy last week. Exports contracted during 6th consecutive month, retail inflation continued To stay well above RBI’s comfort zone, the upper limit for FDI (automatic route) in India’s defense sector was raised from 49% to 74% even as the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance suggested that Indian startups should reduce dependence on foreign funding sources such as the US and China.

And yet the biggest economic news posed as a political event all week. I mean the three agricultural ordinances that the government wants to formally legislate into laws.

There was much consternation when Punjab and Haryana saw widespread protests against the proposed bills. The BJP government led by Narendra Modi even lost one of its oldest allies, the Shiromani Akali Dal, when the SAD Harsimrat Kaur Badal resigned of her ministerial portfolio of Minister of Food Processing Industries.

On the Express, we have followed the protests closely and have repeatedly tried to explain why farmers are not happy with these legislative changes. Despite the rejection, Prime Minister Modi has reiterated that farmers will benefit from the changes, which were first mentioned as part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan package.

Here’s a quick look at what all the fuss is about.

The first thing to do is to simplify the names of these three ordinances as the agricultural economist Sudha Narayanan (of the IGIDR) has done.

Therefore, think of “The Agricultural Products Trade (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020” as the APMC Bypass Ordinance.

Similarly, treat the “Essential Commodities (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020” as the Agribusiness Food Storage Freedom Ordinance and the “Farmers Agreement (Empowerment and Protection) on Price Guarantee and Agricultural Services Ordinance, 2020 ”as the Contract Farming Ordinance.

Farmers protest in Patiala on Wednesday. Express photo of Harmeet Sodhi.

Farmers protest in Patiala on Wednesday. Express photo of Harmeet Sodhi.

So what the former tries to do on paper is allow farmers to sell their products in places other than the mandis regulated by APMC. It is essential to note that the idea is not to close APMC but to expand the options for farmers. Therefore, if a farmer believes that it is possible to achieve a better deal with some other private buyer, instead of selling his product on APMC-mandi, he can choose not to participate.

The second bill proposes to allow economic agents to store food items freely without fear of being prosecuted for hoarding.

The third bill provides a framework for farmers to enter contract farming.

The idea of the three bills is to liberalize agricultural markets in the hope that doing so will make the whole system more efficient and allow better prices for all stakeholders, especially farmers.

The central concern, presumably, is to make Indian agriculture a more profitable business than it is now.

There are two diametrically opposite ways of looking at these changes.

One is to believe that the plan on paper will work perfectly in real life. This would mean that farmers would emerge from the clutches of the APMC-mandis monopoly and the rent-seeking behavior of traditional intermediaries (called Adhtiyas). Henceforth, a farmer could choose who to sell to and at what price after making an informed decision. And more importantly, when you do this, most of the time, you will end up earning more than you used to in the past through exploiters Adhtiyas and APMC-mandis.

📣 Express explained is now in Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay up to date with the latest

The protest in Sirsa on Friday. (Photo Express)

The protest in Sirsa on Friday. (Photo Express)

The polar opposite viewpoint, which is presumably held by protesting farmers, is to view this move towards a greater free market game as a government ploy to move away from its traditional role of being the guarantor of minimum subsistence prices. (MSP). . MSPs work on regulated APMC mandis, not private deals.

Farmers, especially in areas where MSPs are used most prominently, are suspicious of what markets will offer and how so-called “big companies” will treat them. Farmers can influence the most powerful governments through the electoral process, but in the face of big business, they are exposed as minor players, unable to negotiate effectively.

There are no easy answers other than saying that while they both have some valid points, neither point of view is completely correct.

For example, the proposed laws are not closing APMC-mandis, nor do they imply that MSPs will not be functional. Furthermore, it is true that, in all sectors of the economy, liberalization has expanded the size of the pie and improved welfare.

Why shouldn’t a farmer have more options? If private treatment is not clearly better, a farmer can continue as is. If corporate farming succeeds in weakening the APMC-mandi system, then it would only be because hordes of farmers chose corporate farming or selling off the existing mandi. Could it be the case that the Adhtiyas and existing elites are the ones who are threatened by this reform?

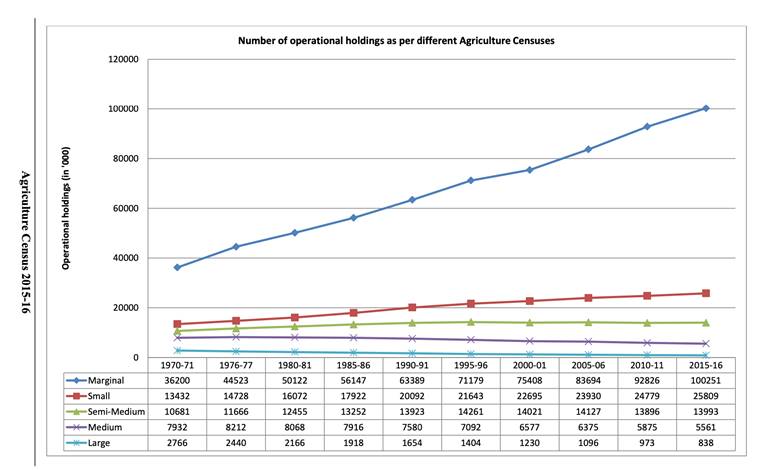

Furthermore, there is an unjustified fascination for MSPs in India. The last agricultural census (2015-16) showed that 86% of all land holdings were small and marginal (less than 2 hectares). See the chart below. The plots are so small that most of the farmers who depend on them are net buyers of food. As such, when PMS is raised, they tend to harm farmers the most!

Land property size chart

Land property size chart

This despite data showing that more and more agricultural products are being sold to private actors, rather than to the government through MSP, already.

On the other hand, you can understand why farmers are so skeptical about markets. A good example is what happened when the government applied a ban on exports of onions. In doing so, the government prioritized the interests of consumers over the interests of farmers (producers).

This is not the first time. There are countless examples where the government’s decision to protect consumers from higher prices has resulted in farmers being deprived of the higher prices that a free market could have provided. Indeed, it can be argued that the MSP is the embodiment of this mistrust.

Another underlying structural problem is the lack of information with farmers, which inhibits their ability to make the best decision for themselves. For example, what is the correct price for your products?

Similarly, in the absence of a proper infrastructure to store their products, they may never have the ability to negotiate effectively, even if they know the correct price.

Ultimately, what will determine the results of this latest set of reforms will be their implementation.

If farmers feel robbed and exploited when they participate more fully in the market, they will blame the political masters, but if they relish success through sustained better yields, allowing them to afford a better standard of living, then there will be doubts about long standing. it will melt down.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay up to date with the latest headlines

For the latest news explained, download the Indian Express app.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

.