Representatives of the 164 member states of the World Trade Organization met last week in Geneva to discuss a proposal by India and South Africa to waive broad sections of the WTO’s intellectual property rules and try to forge an agreement on how to developed the patents in the race against Covid-19 must be recognized.

Read our live coronavirus blog for the latest news and updates.

The meeting ended without consensus, leaving the poorer countries that sponsored the proposal frustrated and the legal protections for vaccines intact. That may be a win for patent protection advocates, but the pressure for change will only increase if billions of people in the poorest countries don’t get vaccinated as the rich world starts receiving a steady stream of doses from Pfizer. Inc and BioNTech SE, Moderna Inc and AstraZeneca.

“With the biggest health crisis we have ever experienced, we still cannot find alternative ways to address intellectual property issues when everyone’s lives are at stake,” said Tahir Amin, executive director of the Medicines, Access and Knowledge Initiative. , an organization that promotes better access to medicines. “You have the defenders saying ‘We broke down the wall’, and then you have the investors saying ‘If we open the door it’s like the floodgates.’ We have to be smarter than that. ”

A patent gives the drug manufacturer exclusive rights to make a vaccine it developed, and it also gives it the power to charge a price that covers research and development costs. Your profit margin per dose, however, depends on the urgency of the situation, and in the midst of a pandemic, charging more than development costs is sure to be controversial. India’s proposal would require the exemption to remain in effect until there is widespread vaccination and the majority of the world’s population has developed immunity.

Whether reconciliation is possible will only become clear as the pandemic unfolds. The European Union and the US, home to the major drugmakers, are vehemently opposed to the proposal, although prices may offer some room for negotiation.

Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have said their vaccine will cost $ 19.50 a dose in the United States. That’s likely too much for many poorer countries, even if discounted, especially given the cost of the vaccine’s freeze storage requirements. But the AstraZeneca vaccine costs between $ 4 and $ 5 per dose and is the great hope for the developing world right now.

The Covax alliance, an effort backed by more than 90 rich countries that seeks to boost access to vaccines in some 90 poor countries, has reached an agreement with AstraZeneca to purchase and distribute vaccines.

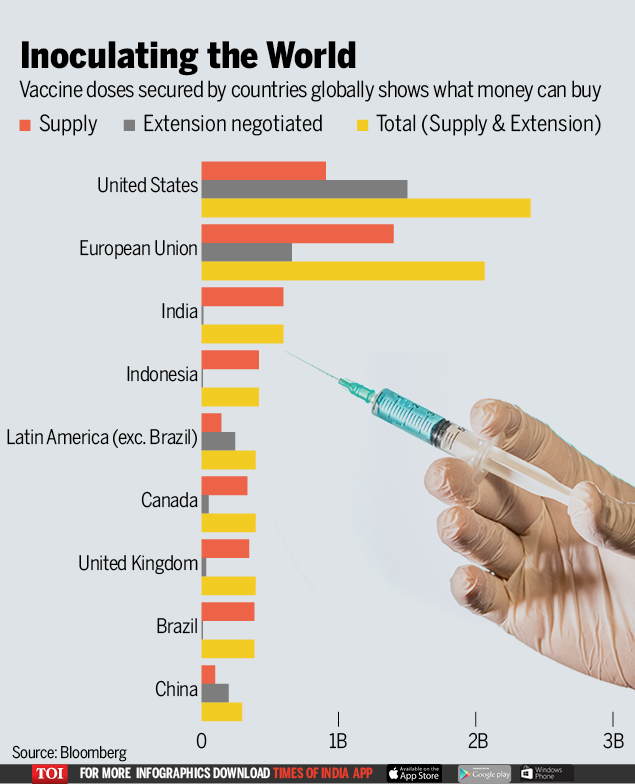

Last month, Covax said it had raised $ 2 billion, but that may not be enough, as it needs another $ 5 billion next year to purchase 2 billion doses. On Tuesday, the EU and the European Investment Bank announced funding of 500 million euros ($ 608 million) to help vaccinate 1 billion people as part of that effort.

“We are an integrated world,” said Fred Abbott, a professor at Florida State University School of Law. “Everyone understands that you can vaccinate everyone in the United States, but if you don’t vaccinate everyone, you will still have a problem.”

However, pressure from developing countries will only increase next year if they are left in the lurch. UNAIDS, the UN agency that fights the immunodeficiency virus, calls it a choice between “a popular vaccine or a for-profit vaccine.”

While the first vaccines have been distributed in recent days in the UK, nine out of 10 people in poor countries will miss a vaccine by 2021, according to Oxfam. That echoes the early days of the AIDS response, UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima said, when “treatment was only available to the rich, while the poorest countries had to wait years.”

The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations argues that patent suspension is dangerous. If you give up patents this time, you risk damaging the entire medical infrastructure that allowed Covid vaccines to be developed in record time, Director General Thomas Cueni said.

“The erosion of patent protections has far-reaching consequences,” he wrote in a recent New York Times op-ed, citing the development of messenger RNA, the underlying innovation common to Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. “Scientists eager to explore future uses of mRNA will have a hard time finding investment if intellectual property protections are taken away when others deem it necessary.”

Drug makers like AstraZeneca have vowed not to benefit from their vaccine for the duration of the pandemic, while Moderna has said it will not enforce its patents during the pandemic. Even frequent critics of drug companies have praised some of these efforts.

There are precedents for countries suspending patents unilaterally, but they have been used seldom since 1945. Enforcement would be difficult: Most patent applications have yet to be issued and it is difficult to force companies to disclose trade secrets such as business processes. manufacturing that there may be wide uses beyond vaccines.

Back at the WTO, delegates agreed to keep discussions open and will present a report to the WTO General Council meeting on December 16, highlighting the “current lack of consensus” on the issue, according to a statement from the organization.

James Pooley, former deputy director general of the World Intellectual Property Organization, acknowledges that while the proposal “is unlikely to go anywhere,” it may have an impact in the future.

“It’s the ram on the gate,” he said. “If they keep hitting it, a hinge can break.”

.