What’s more, it appears that low crop prices have caused agricultural wages in Bihar to remain suppressed compared to Punjab and Haryana and led to labor migration from the state.

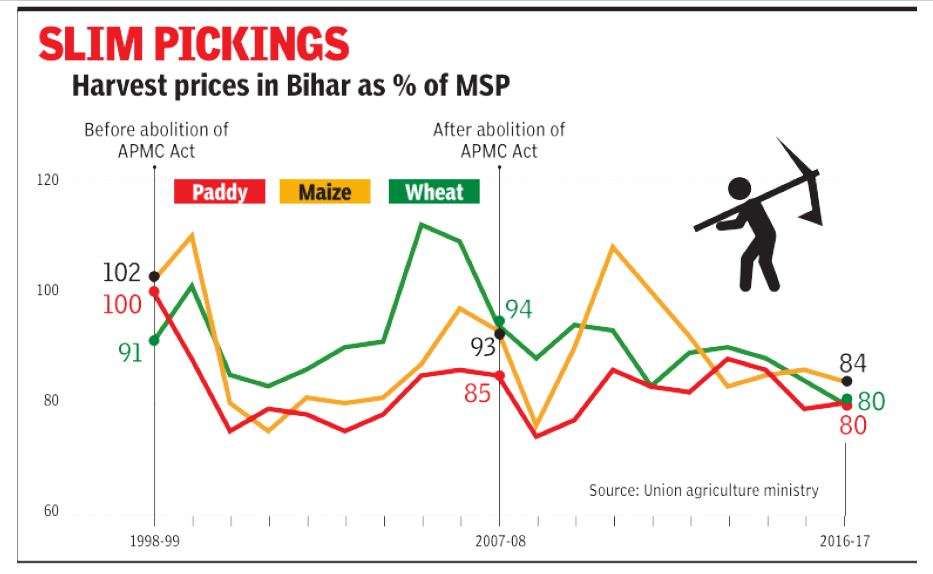

Analysis of agricultural crop prices and MSP of wheat in Bihar from 1998-99 to 2016-17 shows that during nine harvest seasons from 1998-99 to 2006-07, the price of the crop remained above the MSP in three, from 90% to 100%. of MSP in three, and less than 90% of MSP in three. During the same period, prices in Punjab remained above the MSP in three seasons and 90% or more than the MSP in the remaining six seasons. In Haryana, prices were above the MSP in five seasons and 90% or more than the MSP in the remaining four.

The prices of agricultural crops collected by the Ministry of Agriculture are averages of the wholesale prices at which the farmer sells to the merchant at the village site.

Follow TOI’s Live Blog for the latest updates on the farmers’ protest

In the ten marketing seasons between 2007-08 and 2016-17 (the latest data available), not a single season saw prices in Bihar go beyond the MSP. Prices remained at 90% or more of MSP in four seasons and fell even below that level in the remaining six. In Punjab, on the other hand, there were two seasons in which prices exceeded the MSP, while only one saw them fall below 90% of the MSP. Similarly, for seven seasons during this period, farmers in Haryana sold wheat at prices higher than the MSP, while in two seasons prices were between 90% and 100% of. The data was not available for a marketing season in Haryana.

Trends point to prices for the rice crop. Rice is grown in both autumn and winter in Bihar and the higher price of the two is taken for this analysis. Haryana is excluded from this comparison because growing high-quality rice in the state has raised agricultural crop prices much higher than the MSP.

In Bihar, in the nine harvest seasons between 1998-99 and 2016-17, only one saw prices almost on par with MSP (99.5% of MSP), for three prices they were within 80-90% of MSP and for the Five remaining farmers obtained 70 to 80% of the MSP. In the ten seasons between 2007-08 and 2016-17 after the abolition of the APMC law, prices were within 70-80% of the MSP in three and between 80-90% of the MSP in the remaining six.

This raises questions about the claim that farmers are trapped in the MSP and APMC mandi system and that the opening of the market leads to higher prices from companies and private buyers. It also helps explain farmers’ anguish over the MSP’s uncertainty and mistrust in “free markets.”

In Punjab, for the 16 marketing seasons for which data are available from 1998-99, the price of the rice crop fell below the MSP (96.6%) only once and remained higher than the MSP in the rest.

The patterns hold even for corn, which, unlike rice and wheat, is not purchased by the government and is sold mainly to private buyers. In the nine seasons before the abolition of the APMC law, there were two in which maize sold higher than the MSP in Bihar. In the ten seasons following the abolition of mandis, again only two saw prices above the MSP. During the last four seasons, it has remained below 90% of the MSP. In contrast, farmers in Punjab sold maize above MSP in 14 of the 18 seasons for which price data is available. Prices fell below the MSP only four times, but remained between 90% and 100%. In Haryana, prices never fell below MSP.

Data on average daily wages of plowmen or farm workers (data on female labor were not available for all years) between 2005-06 and 2017-18 show that the lower price of production could have abolished agricultural wages in Bihar. In 2006-07, the median wage in Bihar was 79% of wages in Punjab and 66.8% of wages in Haryana. Today, the agricultural labor force in Bihar earns 61% of what it could in Punjab and 50-60% of wages in Haryana, the latter figure being 59.1%.

.