[ad_1]

College students, expelled from campus by the coronavirus, have a new extracurricular activity: litigation.

College students in the US USA They have sued more than 50 schools, demanding partial tuition, room and board and reimbursement of fees after closing.

The proliferation of breach of contract lawsuits, many of them filed in the past week, point to some of the biggest names in higher education: state systems, including the University of California and the State of Arizona, as well as private institutions like Columbia, Cornell and New York University.

Student attorneys, who advertise on sites like Collegerefund2020.com, seek class action status on behalf of hundreds of thousands of students. While legal experts say the lawsuits face huge obstacles, they could involve billions of dollars in claims.

Bloomberg

To justify annual prices that can exceed $ 70,000 a year, universities have long announced their on-campus experience, including close contact with faculty and colleagues who will become a lifelong network.

Now millions of students are studying online. Many of the lawsuits seek compensation for the difference in value between the virtual and in-person experience. The plaintiffs include Grainger Rickenbaker, a freshman who specializes in real estate development and management at Drexel University in Philadelphia, who charges more than $ 50,000 in tuition and another $ 16,000 in room, board, and other fees.

“I’m missing out on everything the Drexel campus has to offer, from libraries, gymnasium, computer labs, study rooms and lounges, dining rooms,” said Rickenbaker, 21, who is demanding a partial refund while working remotely from his home in Charleston, South Carolina.

Most universities declined to comment on the suits. The California State System said it would defend itself against a complaint that underestimates the services it still provides. The state of Arizona said it would grant a $ 1,500 credit to all students who moved out of college before April 15.

Peter McDonough, general counsel for the American Council on Education, a university trade group, said schools are struggling for circumstances beyond their control. They are spending a lot of time and resources to support remote learning, while still paying teachers and bearing other costs, he said.

“The faculty and staff are literally working 24 hours,” said McDonough. “We are in the midst of a catastrophe. Schools are doing everything possible to overcome it.”

Some universities, such as Harvard, Columbia, Middlebury and Swarthmore, have agreed to reimburse for unused room and food. Others are offering credits or haven’t decided what to do, according to Jim Hundrieser, vice president of the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Payments can add up. Small residential institutions, for example, can reimburse $ 2 million to $ 3 million, while large schools with several thousand students on campus are likely to return $ 8 million to $ 20 million or more, Hundrieser said.

For individual students, funds can be of great help in an economic crisis. A university that charges about $ 8,000 for room and board for a semester that was canceled halfway through could be sending students a check for around $ 4,000.

Federal lawsuits vary in their lawsuits. The Anastopoulo Law Firm in Charleston represents students in approximately a dozen schools, including Drexel, and is seeking a partial return of all unreimbursed payments.

In his lawsuits on behalf of students at California public universities, Chicago-based DiCello Levitt Gutzler only requests the refund of student fees for items such as transportation and student organizations, which however can number in the thousands dollars a year.

Both the University of California and California state systems have already agreed to return unused room and board. Cal State said it is still providing services, such as counseling, and will reimburse fees “that have not been earned by the campus.”

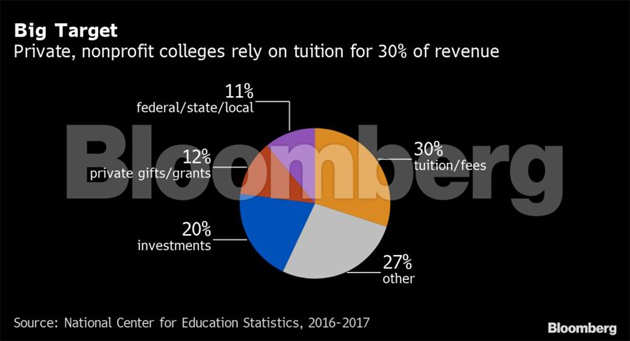

However, the complaints are settled, highlighting the stakes for the higher education industry of more than $ 600 billion a year. Public universities depend on tuition and fees for 20% of their total income; private nonprofit schools, 30%, according to the latest federal data.

In the fall, if many schools open online only, they would lose room and board fees and face pressure to charge less tuition. Many predict that the pandemic will drive financially fragile institutions out of business.

Universities can expect to see more lawsuits soon, threatening what attorney Anthony Pierce called “an economic tsunami.” On Thursday alone, the students filed complaints against Pennsylvania State University, Brown and the University of Pennsylvania, which called the lawsuit against them “misdirected and without merit.” Brown said the crisis has not changed the “core value” of his education.

“The plaintiffs’ bar sees an opportunity here,” said Pierce, a partner who runs the Washington office of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer and Feld LLP who recently alerted universities to the risks of the suits.

The result may depend on the paperwork signed by both parties. Students are more likely to prevail if they can pinpoint contractual terms that require specific services, according to Joe Brennan, a professor at the Vermont Law School who is tracking the litigation.

Students generally have housing contracts, as do apartment tenants, said Barry Burgdorf, a former general counsel for the University of Texas system now at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. Families generally do not have written agreements detailing exactly what tuition covers.

Universities will probably argue that they are exempt from past obligations because the pandemic and government shutdown orders made regular service provision impossible.

Even if students cannot pinpoint particular contractual provisions, they are making “unfair enrichment” claims, arguing that it is unfair for schools to benefit from services they did not provide.

Some of the lawsuits seek compensation for what is known as “diminished value,” or the difference between the value of an on-campus and an online education.

Depending on how the courts view any disparity, the amounts could exceed housing reimbursements. (However, many students pay much less than the published tuition prices due to scholarships.)

Still, courts have been reluctant to try to value one type of title over another, according to Burgdorf. Another challenge: If the judges don’t grant class action status, most students would not consider it worthwhile to file claims on their own.

Some students, like Joshua Zhu, a Cornell senior, have not signed a lawsuit, but they are encouraging from the sidelines and could ultimately benefit. The 22-year-old information science student is entering classes from an off-campus apartment in Ithaca, New York, where he battles irregular Wi-Fi and misses working in an artificial intelligence lab.

“The tuition we paid to come to Cornell was with the expectation that we would have in-person classes and whatever came along with that,” said Zhu. “It almost seems like a breach of contract.”

[ad_2]