[ad_1]

Even before this interviewer can finish the question, “Has anyone ever told you it was a crazy idea?” Bob Balaram intervenes: “Everyone. All the time.”

This “crazy idea” is the Mars Helicopter, currently at Kennedy Space Center, hoping to hook up with Red Planet on the Mars Perseverance rover this summer.

Although Balaram probably didn’t know it at the time, the seed for an idea like this emerged for him in the Apollo era of the 1960s, during his childhood in South India. Her uncle wrote to the United States Consulate requesting information about NASA and space exploration. The bulky envelope they sent, filled with glossy brochures, captivated young Bob. His interest in space was further awakened by listening to the moon landing on the radio. “I gobbled it up,” he says. “Long before the internet, the United States had a good reach. You had my eyeballs.

His active brain and fertile imagination focused on obtaining an education, which would lead to a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology, a Master’s and a PhD. in computer and systems engineering from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and a career at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. That is where he has remained for 35 years as a robotics technologist.

Balaram’s career has spanned robotic arms, early Mars rovers, technology for a notional balloon mission to explore Venus, and a stint as a leader for Mars Science Laboratory’s entry, descent, and landing simulation software.

Going through obstacles, red tape and the Martian atmosphere

As with many innovative ideas, it took a village to make the helicopter happen. In the 1990s, Balaram attended a professional conference where Stanford professor Ilan Kroo discussed a “mesicopter,” a miniature airborne vehicle for ground applications that was funded as a proposal for NASA Advanced Innovative Concepts.

This led Balaram to think about using one on Mars. He suggested a joint proposal with Stanford for the presentation of a NASA research announcement and recruited AeroVironment, a small company in Simi Valley, California. The proposal received rave reviews, and while it was not selected for funding at the time, it did throw a shovel rotor test under Mars conditions at JPL. Apart from that, the idea “sat on a shelf” for 15 years.

Fast forward to a conference where the University of Pennsylvania presented on the use of drones and helicopters. Charles Elachi, then JPL director, attended that session. When he returned to JPL, he asked if something like this could be used on Mars. A colleague from Balaram mentioned his previous work in that area of research. Balaram dusted off that proposal, and Elachi asked him to write a new one for the competitive call for research payloads for Mars 2020. This sped up the process of developing a concept.

Balaram and his team had eight weeks to submit a proposal. Working day and night, they met the deadline with two weeks to spare.

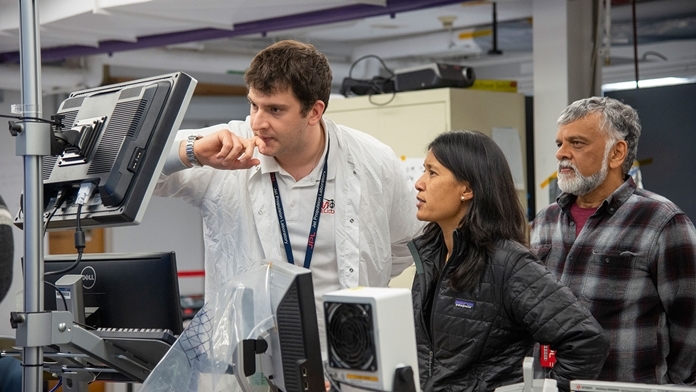

Although the helicopter idea was not selected as an instrument, it was funded for technology development and risk reduction. Mimi Aung became manager of the Mars Helicopter project, and after the team worked on risk reduction, NASA decided to fund the helicopter for the flight as a technology demonstration.

Building and testing a beast

So the reality was established: how do you build a helicopter to fly on Mars and make it work?

It is not an easy task. Balaram describes it as a perfectly blank canvas, but with restrictions. His training in physics helped him imagine flying on Mars, a planet with an atmosphere that is only 1% as dense as Earth’s. He compares it to flying on Earth at an altitude of 100,000 feet (30,500 meters), about seven times higher than what a typical land helicopter can fly. Another challenge was that the helicopter could carry only a few kilograms, including the weight of the batteries and a radio for communications. “You can’t throw mass at it, because it needed to fly,” he says.

Balaram realized that it was like building a new type of aircraft that turns out to be a spaceship. And because he is a “passenger” on an iconic mission, he says, “we have to 100% guarantee that it will be safe.”

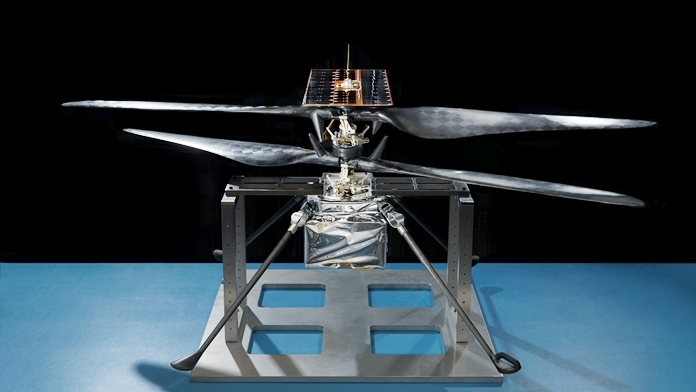

The end result: a 4-pound (1.8 kilogram) helicopter with two pairs of lightweight counter-rotating blades, one upper and one lower, to traverse the Martian atmosphere. Each pair of blades spans 4 feet (1.2 meters) in diameter.

Once it was built, Balaram says the question was, “How is this beast tested? There is no book that tells how.” Because there is no easily accessible place on Earth with a thin atmosphere like Mars, they conducted tests in a vacuum chamber and in the 25-foot Space Simulation Chamber at JPL.

Approximately two and a half months after landing in Jezero crater, the Mars Helicopter team will have a window of approximately 30 days to conduct a technology demonstration in the planet’s real environment, starting with a series of vehicle checks, followed by attempts of first flights in the very thin Martian atmosphere.

Despite the best efforts and best tests available on Earth, this is a demonstration of high-risk, high-reward technology, with Balaram frankly saying, “We could fail.”

But if this “crazy idea” succeeds on Mars, it will be what Balaram describes as “a kind of Wright brothers moment on another planet,” the first time a powered plane has flown on Mars, or on any other planet as well. from Earth, for that matter. This potential advance could help pave the way for future ships that would expand NASA’s vehicle portfolio to explore other worlds.

And in part because there have been so many challenges along the way, it is a testament to the dedication, vision, persistence, and attitude of Balaram and his colleagues that the Mars Helicopter concept was funded, planned, developed, and built and is aimed at Red planet. this summer.

Bob is the inventor of our Mars helicopter. They innovated design and followed that vision until it became a chief engineer at all stages of design, development and testing, “says project manager Aung.” Every time we encounter a technical obstacle, and encounter many obstacles, we always resort to Bob, who always has an endless set of possible solutions to consider. Come to think of it, I don’t think I’ve ever seen Bob feel trapped at any time! “

Home extends to Mars

The primary objective of the Mars 2020 mission is to deliver the Perseverance rover, which will not only continue to explore the planet’s past habitability, but will actually look for signs of ancient microbial life. It will also cache rock and soil samples for collection for a possible future mission and help pave the way for future human exploration of Mars. Even if the helicopter encounters difficulties, the science gathering mission of the Perseverance rover will not be affected.

Balaram notes that in addition to the usual “seven minutes of terror” experienced by the team on Earth during a landing on Mars, once the helicopter is on Mars and attempts to fly, “these are the seven seconds of terror each time we take off. ” or land. “

Does Balaram care about all this, even a little? “There has been a crisis every week for the past six years,” he says. “I’m used to it.”

Balaram eliminates any stress that may arise through backpacking, hiking and massage. There is also his very supportive wife, Sandy, who has a title on the team and his own acronym: CMO or CEO of Moral. She has regularly baked cakes, pies and other goodies for Balaram to share with his colleagues for sustenance during the long process.

And he praises his teammates on the Mars Helicopter project, saying that the people attracted to him are agile and move fast. “They are a great team, determined to challenge powerful things, that’s the fun part,” says Balaram. His opinion on bold and powerful things: “Good ideas don’t die, they only take a while.”