India is battling one of the world’s highest coronavirus cases, its worst economic downturn, factories closed, farmer protests and the deadliest border fight with China in decades.

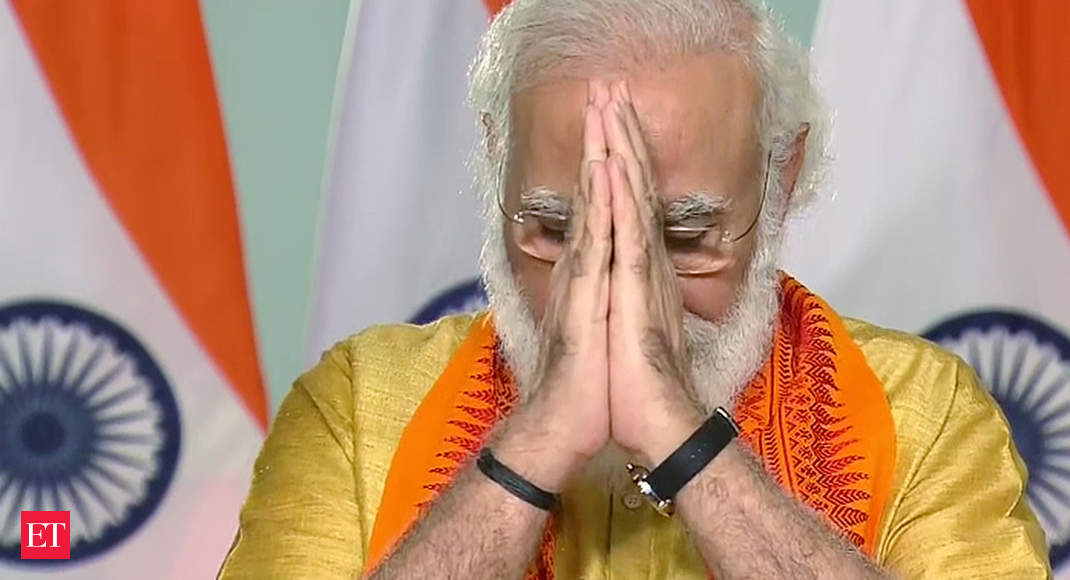

However, Prime Minister Narendra Modi seems to remain as popular as ever. Opinion polls in Bihar, where he faces his first major electoral test since the pandemic from October 28 to November 7, show that his coalition is comfortably retaining control of the state government. A separate India Today “Mood of the Nation” survey in August said 78% rated their performance “good to outstanding” compared to 71% last year.

One such supporter is Sanjay Kumar, 22, a carpenter who was beaten by police in April for violating India’s strict blockade while cycling from New Delhi to his village in Bihar, a journey of more than 1,000 kilometers. , after losing your job. Still can’t find a regular job.

“Some people are not getting all the benefits due to the corruption in the medium and that is not their fault,” Kumar said, noting that Modi cannot control the spread of the virus if people do not wear masks. “No one can question their good intentions,” he said. “He is doing everything possible to give food and work to the poor.”

Many other Modi supporters also blame others for India’s troubles, and there is no shortage of targets: central government bureaucrats, state governments, village leaders, opposition parties, and even their fellow citizens. The prime minister has helped enchant the poor of India by meeting their daily needs with programs to supply gas for cooking, toilets and housing, all while sticking to a right-wing playbook.

Weak opposition

In the absence of significant national opposition, voters have been willing to give Modi a very long leash, according to Milan Vaishnav, director and senior fellow of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“This kind of policy, however, is not without its flaws,” Vaishnav said. “Mr Modi was able to make this argument effectively in 2019, but it will be more difficult in 2024 if he cannot achieve faster progress in the economy, employment and governance.”

As prime minister, Modi has been focused on making India attractive to global investors and blatantly majority. His Bharatiya Janata party returned to power in May of last year with an overwhelming majority following a campaign that highlighted his success in providing needs for the poor, combined with a majority nationalist agenda that played out his strongman persona, particularly against archrival Pakistan. .

Since winning reelection, Modi has repealed article 370 of the constitution that granted special autonomous status to the only Muslim-majority state in India, Jammu and Kashmir, and passed a citizenship law that discriminates on the basis of religion. He has also promoted a national registry of citizens in Assam and laid the foundation stone for the construction of the Ram temple at the controversial site of Ayodhya.

A spokesperson for Modi’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“It is popular because it has ideological clarity and is only implementing what the BJP had promised in its manifesto, such as the promise to repeal Article 370,” said Arun Anand, research director of the Delhi-based think tank Vichar Vinimay Kendra and author of two books on the parent organization of the BJP, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. “Politicians who keep their word are rare in India.”

Modi has positioned himself alongside other populist leaders around the world who feed on the anxiety that minority groups will one day supplant the majority despite the fact that Hindus make up 80% of India’s population, according to Sudha Pai. , a political scientist, author and scientist based in New Delhi. former Vice Chancellor of the Center for Political Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He has also been adept at leaving the details of policies to ministers and bureaucrats, who take the blame if something goes wrong, he said.

“Now we have a populist regime that has created a leader who can do no wrong,” Pai said. “He has this way of speaking like a man-god.”

Controlling the narrative

Modi has shown that he can turn unrest into political gain. In 2016, its decision to abruptly withdraw 86% of the currency in circulation with a four-hour notice led to a prolonged shortage of cash and an economic slowdown that caused difficulties across India. Still, his party overwhelmingly won a key state a few months later, as his party told voters that it helped curb corruption and tax evasion, though it ultimately failed to achieve its goal.

Part of his success is the ability to control the narrative. Modi has not held a single press conference as prime minister during his six years in power, but has reached out directly to the masses through a weekly radio show and posts on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. His party’s social media army has deflected the blame for the problems, including the opposition parties.

“Modi’s ability to get his message across directly to people is second to none,” said Neelanjan Sircar, assistant professor at Ashoka University and visiting principal investigator at the Center for Policy Research. “I am increasingly convinced of the connection between creating a powerful charismatic leader and a media-controlled narrative. How do you build trust in someone? You keep telling stories that build your credibility. ”

As the Covid-19 outbreak in India became one of the fastest growing in the world, Modi shared a carefully choreographed video in August showing him feeding peacocks at his official New Delhi residence during your morning exercise regimen. Such images have helped cement an image of Modi as “a monk-like ascetic who can be trusted with life,” said Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a political analyst who has written a biography on Modi.

Sahebrao Patil, a 60-year-old driver in Maharashtra who suffered a loss of income after the shutdown, is among those who say Modi can’t go wrong.

“I believe with all my heart that Modi cannot lie,” he said. “We don’t even ask who the candidate is. We just voted for Modi. ”

.