Updated: September 16, 2020 6:58:41 am

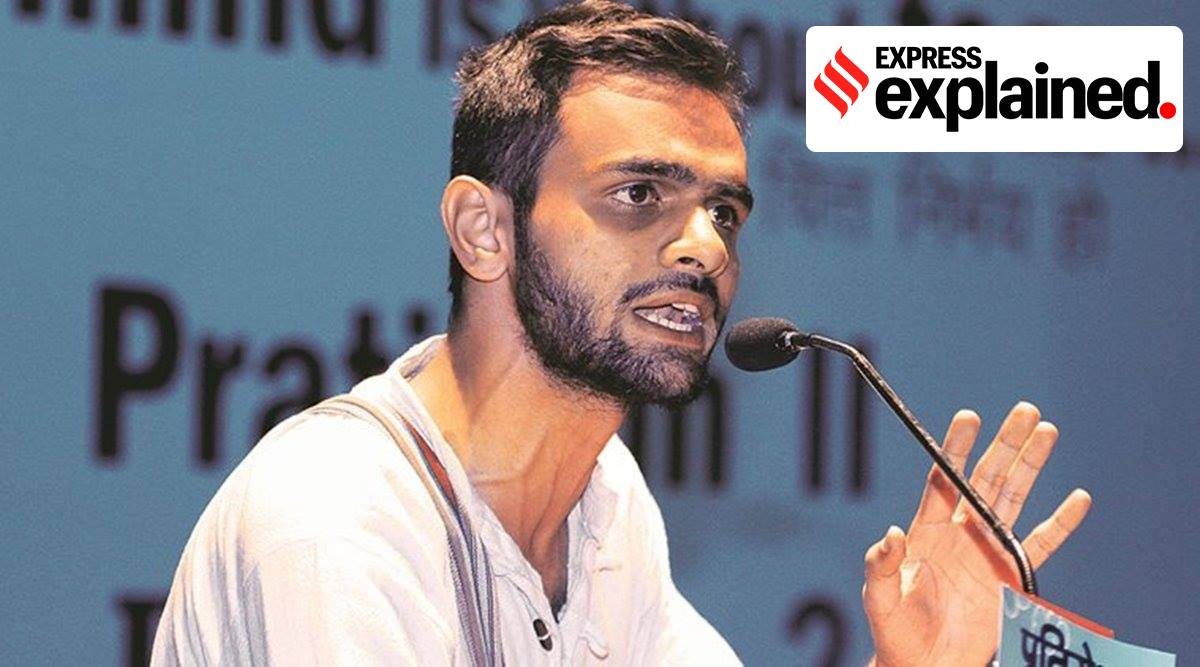

Umar Khalid is one of several young activists who have been arrested in cases related to the violence in Delhi in February. The police have invoked UAPA provisions to investigate the alleged “larger conspiracy” behind the riots.

Umar Khalid is one of several young activists who have been arrested in cases related to the violence in Delhi in February. The police have invoked UAPA provisions to investigate the alleged “larger conspiracy” behind the riots.

On Monday, Delhi police obtained 10 days of custody of former Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) student Umar Khalid, who had been arrested one day before in a case registered under the Law of (Prevention) of Illegal Activities (UAPA).

Khalid is one of several young activists who have been arrested in cases related to the violence in Delhi in February. The police have invoked UAPA provisions to investigate the alleged “larger conspiracy” behind the riots.

What is UAPA and what is it used for?

The UAPA is primarily an anti-terrorist law, aimed at “more effectively preventing certain illicit activities of individuals and associations and dealing with terrorist activities.” It was first enacted in 1967 to target secessionist organizations and is considered the predecessor of laws such as the (now repealed) Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) and the Terrorism Prevention Act (POTA).

Amendments from time to time have made the UAPA stricter. After the last amendment in 2019, a person can be designated as a terrorist; only organizations can be designated earlier. UAPA cases are tried by special courts.

The law has been used in cases other than conventional “terrorism” or “terrorist acts”. Lately it has been invoked against activists, student leaders and journalists. UAPA cases against activists have been filed in the Bhima-Koregaon case; at least two journalists in Kashmir; Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal, members of the collective of Pinjra Tod students; the former municipal councilor of the Congress Ishrat Jahan; Khalid Saifi of the United Against Hate organization; Jamia Millia Islamia’s student, Safoora Zargar; and now, Umar Khalid.

📣 Express explained is now in Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@ieexplained) and stay up to date with the latest

What do the police say in the case against Khalid and others?

The investigation is based on FIR 59 of 2020, which has included Sections 302 (homicide) 153A (promotion of enmity between different groups for reasons of religion, etc.) of the IPC, 124A (sedition), among others. .

The core of the police case is that the February 2020 “communal disturbance incidents” in Delhi were “pre-planned” by Khalid and the others. Khalid is accused of giving provocative speeches and urging people to hit the roads to ensure that “minority propaganda in India is being persecuted” is made public during the visit of US President Donald Trump (24 to February 25).

The police have also claimed to have gathered evidence against the defendants in the form of WhatsApp chats that were allegedly used in the “execution of the conspiracy”, alleged witness statements and evidence of the receipt of funds from India and abroad.

Read also | Before UAPA arrest, hasty goodbyes at Umar Khalid’s home

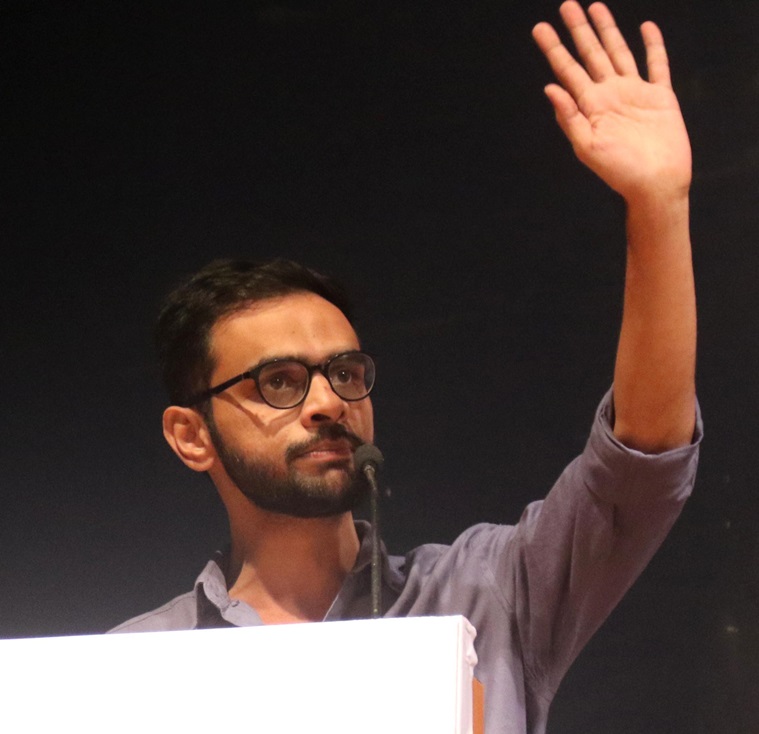

Umar Khalid at a conference in Mumbai in January. (PhotoL Ganesh Shirsekar Express)

Umar Khalid at a conference in Mumbai in January. (PhotoL Ganesh Shirsekar Express)

What provisions of the UAPA have been used in the FIR?

Later, articles 13, 16, 17 and 18 of the UAPA were added to the case.

The Act defines unlawful activity as any action – words, signs or visible representation, spoken or written – that is intended or supports any claim to bring about the secession of any part of India or that incites someone to secession; denies, questions, disturbs or intends to disturb the sovereignty and territorial integrity of India; and “which causes or is intended to cause discontent against India.”

The word “disaffection” has not been defined in the law and is only mentioned once.

Article 13 (“Punishment for illegal activities”), which has been invoked against Khalid and others, provides up to seven years in prison for anyone who “defends, incites, advises or incites the commission of any illegal activity”.

Article 16 (“Punishment for a terrorist act”) specifies the punishment with death or imprisonment for life in the event that a death has occurred as a result of the act. The law defines a terrorist act as one that is intended to threaten or is likely to threaten the unity, integrity, security or sovereignty of India, and causes or is likely to cause death or injury and damage to property.

Section 17 provides for punishment for raising funds for terrorist acts, and section 18 deals with the conspiracy behind the terrorist act or “any preparatory act for the commission of a terrorist act.”

How do the Delhi police justify invoking the anti-terrorism law?

While critics have argued that dissenting or protesting peacefully would not amount to causing “disaffection against India,” police have told the court that the riots were the result of a larger conspiracy to “intimidate the machinery of government.” and that the conspirators had a “Specific Purpose, Object and Mandate” to cause “disaffection and revolt against the Government of India.”

The prosecution has argued that the objective of the protests was “to destroy, destabilize and disintegrate the Government of India to force it to withdraw the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the alleged National Registry of Citizens.”

Also in Explained | Ease of Doing Business: How States Are Ranked, What’s Different Now

What makes the UAPA stricter than other laws?

Safoora Zargar is the only one of the defendants booked under the UAPA who has received bail. But he was granted aid on humanitarian grounds: the Delhi High Court did not deal with his bail case.

Three people from the Popular Front of India (PFI) were released on bail in March, but that was before the UAPA provisions were added to the case.

It is rare for a defendant to easily obtain bail in a UAPA case. The court may reject the bond if in its opinion the case is “prima facie” true. A defendant cannot request an advance bond, and the investigation period can be extended to 180 days from 90 days at the request of the prosecutor, which means that the defendant has virtually no chance of obtaining a default bond.

In UAPA cases, police custody can also be extended to 30 days compared to the 15 days allowed in ordinary criminal cases.

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For the latest news explained, download the Indian Express app.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd

.