Astronomers have found a potential sign of life high up in the atmosphere of neighboring Venus – hinting that there may be strange microbes living in sulfuric acid-laden clouds on the greenhouse planet.

Two telescopes in Hawaii and Chile detected in the dense Venetian clouds the chemical signature of phosphine, a noxious gas that on Earth is only associated with life, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Several outside experts, and the study authors themselves, agreed that this is tempting, but said it is far from the first proof of life on another planet. They said it does not meet the standard of “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” set by the late Carl Sagan, who speculated about the possibility of life in the clouds of Venus in 1967.

“It’s not hard evidence,” said study co-author David Clements, an astrophysicist at Imperial College London. “It’s not even gunshot residue on the hands of your prime suspect, but there is a distinctive cordite smell in the air that may be suggesting something.”

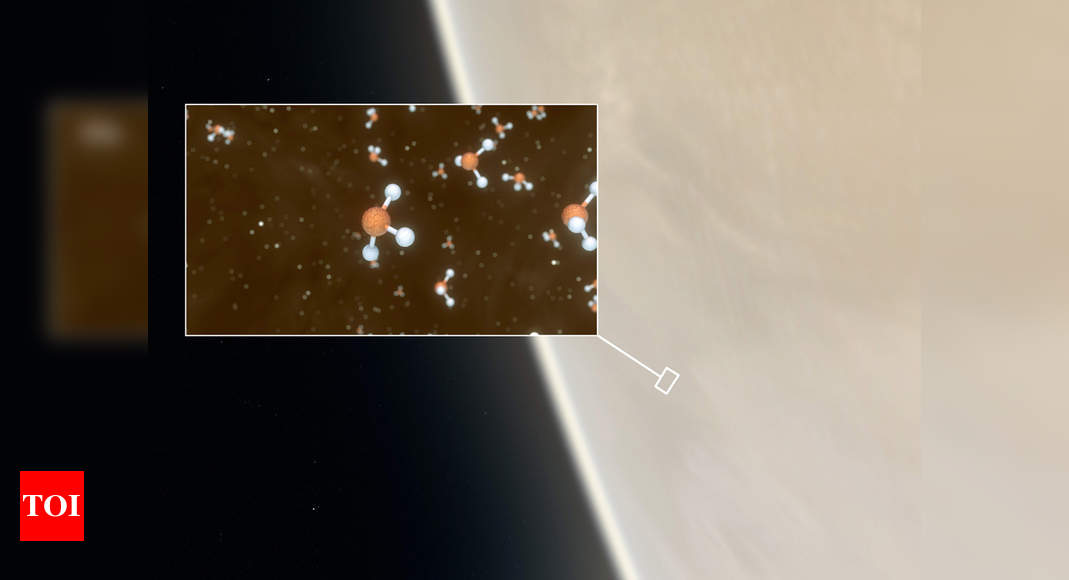

As astronomers plan to search for life on planets outside our solar system, an important method is to look for chemical signatures that can only be obtained through biological processes, called biological signatures. After three astronomers met in a bar in Hawaii, they decided to look that way at the planet closest to Earth: Venus. They looked for phosphine, which is three hydrogen atoms and one phosphorous atom.

On Earth, there are only two ways phosphine can be formed, the study authors said. One is in an industrial process. (The gas was produced for use as a chemical warfare agent in World War I.) The other way is as part of some kind of little-known function in animals and microbes. Some scientists consider it a waste product, others do not.

Phosphine is found in “the exudate from the bottom of ponds, in the guts of some creatures like badgers, and perhaps most unpleasantly associated with piles of penguin guano,” Clements said.

Study co-author Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT, said the researchers “exhaustively analyzed all the possibilities and ruled out all of them: volcanoes, lightning, small meteorites falling into the atmosphere … Not a single process that we analyzed could produce phosphine in amounts high enough to explain our team’s findings. ”

That leaves life.

Astronomers hypothesize a scenario of how life could exist on the inhospitable planet where surface temperatures hover around 800 degrees (425 degrees Celsius) without water.

“Venus is hell. Venus is kind of an evil twin to Earth,” Clements said. “Clearly, something went wrong, very wrong, with Venus. She is the victim of a runaway greenhouse effect.”

But that is superficial.

Seager said all the action can be 30 miles (50 kilometers) above the ground in the cloud cover of the thick layer of carbon dioxide, where it is at room temperature or a little warmer. It contains droplets with small amounts of water but mainly sulfuric acid which is one billion times more acidic than what is found on Earth.

The phosphine could come from some kind of microbes, probably single-celled, inside those droplets of sulfuric acid, which live their entire lives in clouds 10 miles deep, Seager and Clements said. When the drops fall, the potential life likely dries up and could then be collected in another drop and revived, they said.

Life is definitely a possibility, but more proof is needed, several outside scientists said.

Cornell University astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger said the idea of this being the signature of biology at work is exciting, but said we don’t know enough about Venus to say that life is the only explanation for phosphine.

“I’m not skeptical, I have doubts,” said Justin Filiberto, a planetary geochemist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, who specializes in Venus and Mars and is not part of the study team.

Filiberto said that the phosphine levels found could be explained by the volcanoes. He said recent studies that were not taken into account in this latest research suggest that Venus may have many more active volcanoes than was originally thought. But Clements said the explanation would make sense only if Venus was at least 200 times more volcanically active than Earth.

David Grinspoon, a Washington-based Planetary Science Institute astrobiologist who wrote a book in 1997 suggesting that Venus could harbor life, said the finding “ almost seems too good to be true. ”

“I’m excited, but I’m also cautious,” Grinspoon said. “We found an encouraging sign that demands that we follow up.”

NASA hasn’t sent anything to Venus since 1989, although Russia, Europe and Japan have sent probes. The US space agency is considering two possible missions to Venus. One of them, called DAVINCI +, would enter the Venetian atmosphere as early as 2026.

Clements said his head tells him “there’s probably a 10% chance it’s life,” but his heart “obviously wants it to be a lot bigger because it would be so exciting.”

Two telescopes in Hawaii and Chile detected in the dense Venetian clouds the chemical signature of phosphine, a noxious gas that on Earth is only associated with life, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Several outside experts, and the study authors themselves, agreed that this is tempting, but said it is far from the first proof of life on another planet. They said it does not meet the standard of “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” set by the late Carl Sagan, who speculated about the possibility of life in the clouds of Venus in 1967.

“It’s not hard evidence,” said study co-author David Clements, an astrophysicist at Imperial College London. “It’s not even gunshot residue on the hands of your prime suspect, but there is a distinctive cordite smell in the air that may be suggesting something.”

As astronomers plan to search for life on planets outside our solar system, an important method is to look for chemical signatures that can only be obtained through biological processes, called biological signatures. After three astronomers met in a bar in Hawaii, they decided to look that way at the planet closest to Earth: Venus. They looked for phosphine, which is three hydrogen atoms and one phosphorous atom.

On Earth, there are only two ways phosphine can be formed, the study authors said. One is in an industrial process. (The gas was produced for use as a chemical warfare agent in World War I.) The other way is as part of some kind of little-known function in animals and microbes. Some scientists consider it a waste product, others do not.

Phosphine is found in “the exudate from the bottom of ponds, in the guts of some creatures like badgers, and perhaps most unpleasantly associated with piles of penguin guano,” Clements said.

Study co-author Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT, said the researchers “exhaustively analyzed all the possibilities and ruled out all of them: volcanoes, lightning, small meteorites falling into the atmosphere … Not a single process that we analyzed could produce phosphine in amounts high enough to explain our team’s findings. ”

That leaves life.

Astronomers hypothesize a scenario of how life could exist on the inhospitable planet where surface temperatures hover around 800 degrees (425 degrees Celsius) without water.

“Venus is hell. Venus is kind of an evil twin to Earth,” Clements said. “Clearly, something went wrong, very wrong, with Venus. She is the victim of a runaway greenhouse effect.”

But that is superficial.

Seager said all the action can be 30 miles (50 kilometers) above the ground in the cloud cover of the thick layer of carbon dioxide, where it is at room temperature or a little warmer. It contains droplets with small amounts of water but mainly sulfuric acid which is one billion times more acidic than what is found on Earth.

The phosphine could come from some kind of microbes, probably single-celled, inside those droplets of sulfuric acid, which live their entire lives in clouds 10 miles deep, Seager and Clements said. When the drops fall, the potential life likely dries up and could then be collected in another drop and revived, they said.

Life is definitely a possibility, but more proof is needed, several outside scientists said.

Cornell University astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger said the idea of this being the signature of biology at work is exciting, but said we don’t know enough about Venus to say that life is the only explanation for phosphine.

“I’m not skeptical, I have doubts,” said Justin Filiberto, a planetary geochemist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, who specializes in Venus and Mars and is not part of the study team.

Filiberto said that the phosphine levels found could be explained by the volcanoes. He said recent studies that were not taken into account in this latest research suggest that Venus may have many more active volcanoes than was originally thought. But Clements said the explanation would make sense only if Venus was at least 200 times more volcanically active than Earth.

David Grinspoon, a Washington-based Planetary Science Institute astrobiologist who wrote a book in 1997 suggesting that Venus could harbor life, said the finding “ almost seems too good to be true. ”

“I’m excited, but I’m also cautious,” Grinspoon said. “We found an encouraging sign that demands that we follow up.”

NASA hasn’t sent anything to Venus since 1989, although Russia, Europe and Japan have sent probes. The US space agency is considering two possible missions to Venus. One of them, called DAVINCI +, would enter the Venetian atmosphere as early as 2026.

Clements said his head tells him “there’s probably a 10% chance it’s life,” but his heart “obviously wants it to be a lot bigger because it would be so exciting.”

.