September 6, 2020 8:02:05 am

Migrant workers return to New Delhi from parts of Uttar Pradesh on August 10, 2020 (Photo Express: Praveen Khanna).

Migrant workers return to New Delhi from parts of Uttar Pradesh on August 10, 2020 (Photo Express: Praveen Khanna).

Dear readers,

The past week has once again been quite hectic for the Indian economy.

The most important news was the publication of national income data for the first quarter of the current financial year. the GDP shrinks by almost 24% And most economists now expect India’s GDP to shrink by about 10% in 2020-21.

The second major development was the pardon to Bharti Airtel and Vodafone Idea. In the case of annual gross revenue, the Supreme Court allowed telecommunications companies to pay their fees in a staggered over the next 10 years. Previously, these companies were expected to pay at once; doing so would have ruined their viability and, in the process, hurt this rapidly growing sector of the Indian economy.

This week also saw the end date of the moratorium on loan repayment. The focus now shifts to the RBI, which is expected to set the rules that will determine how existing loans will be restructured. This is the main event to watch for next week. It is understood that the KV Kamath committee, which was formed by the RBI to suggest the rules for loan restructuring, has presented its report. Loan restructuring is crucial for many companies that can go bankrupt if their terms and repayment schedule are not changed.

However, it is important to go back to the GDP data and reflect on the key findings and policy implications.

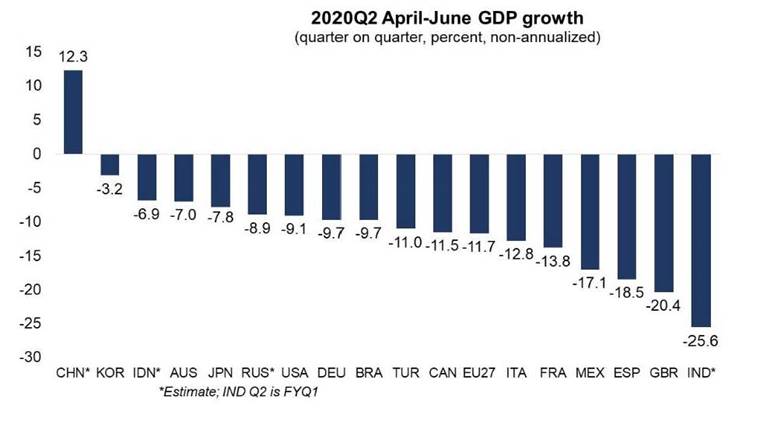

The first thing to keep in mind is that no matter how GDP growth was calculated (qoq, yy, annualized or non-annualized), India is the country most affected among major economies (see chart below; IMF source).

The fact that India’s economy is the worst hit among its global peers is not surprising for two reasons.

One, India had been steadily losing its growth momentum for the past three years; it grew just 3% in the quarter just before Covid’s arrival.

Source: IMF

Source: IMF

Two, since then India has been steadily rising through the ranks of the worst affected countries. At the last count, added more than 80,000 new cases in just one day. That’s not only more than the total cases in China, but also the new record for a single day since the outbreak of the pandemic.

The second key takeaway: how Analysis explained on GDP data showed earlier in the week – is that the government has to spend substantially more if the Indian economy is to recover soon.

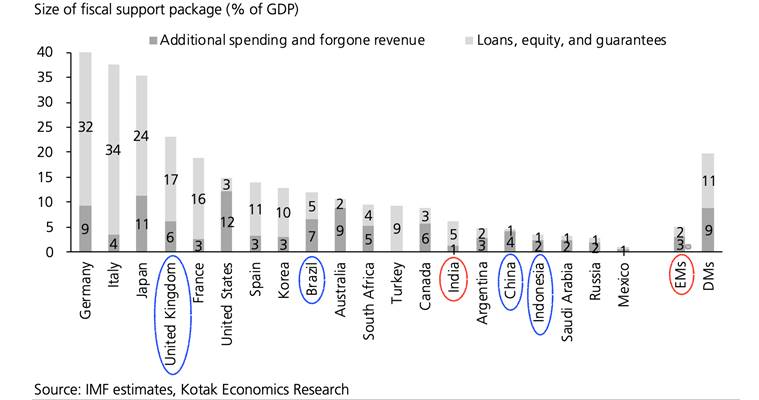

This is also not surprising because even before the GDP data was released, it was repeatedly pointed out by many: including this newsletter – that the fiscal impulse in the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan package of 20 rupees lakh crore it was quite weak and will probably delay recovery.

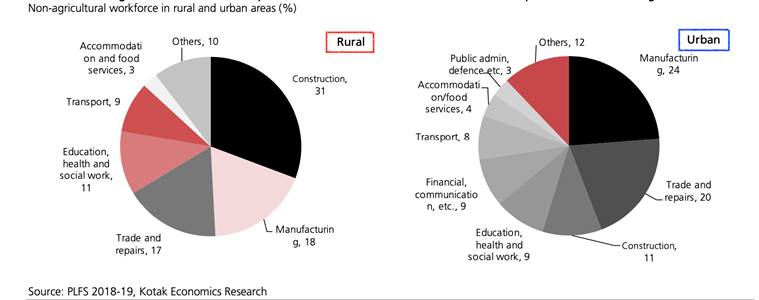

The third key conclusion is that the sectors most affected are those that create the most new jobs for both urban and rural Indians. The graph below (source: Kotak Economic Research) shows how construction (which contracted by 50% in the first quarter), manufacturing (which contracted by 39%), and commerce, hotels and other services (which contracted by 47%) create the largest amount of non-agricultural products. jobs in both rural and urban India.

The fourth key takeaway is that with incomes falling overall, job prospects worsening, and with no clear fiscal stimulus on the horizon, most Indians are likely to save more than they spend. This reduction in your propensity to consume will further delay the recovery process. Surely if everyone spent all the money they had, aggregate demand and GDP growth would pick up quickly. If everyone decides to save all the money, demand will continue to plunge and the economy will struggle for a long time.

Source: Kotak Economic Research

Source: Kotak Economic Research

What are the political implications?

The most important is that the government should lead from the front rather than hiding behind RBI-led credit schemes.

As the graph below shows (source: Kotak Economic Research), so far the Indian government has spent less (in terms of% of GDP) among its peers, be it the BRICS or any other comparable country such as the UK or Indonesia. In fact, India’s direct additional spending is only one third of the average among emerging economies and one ninth of the average among developed countries.

The other big policy question is: how should the government spend the extra money?

Here it deserves a reference to the two rulers of India’s past that I mention in the headline.

Source: Kotak Economic Research

Source: Kotak Economic Research

Asaf-ud-Daula was the Nawab of Oudh between 1748 and 1797. In 1775, he moved the capital of Oudh from Faizabad (near Ayodhya) to Lucknow. In terms of economic policy making, it was quite Keynesian. Whenever there was a famine or a downturn in economic activity, Asaf-ud-Daula employed the poor to build a new building of some kind instead of food or money.

This policy resulted in many iconic Lucknow structures such as Bara Imambara and Rumi Darwaza and earned him the saying “jis ko na de maula, usko de Asaf-ud-Daula” (Those who are disappointed even by the Almighty are served by Asaf-ud -Daula). This is relevant at a time when the government of India has tried to go out of its way by claiming that the current poor state of the economy is an act of God.

While Asaf-ud-Daula was the master in providing immediate aid to the poor, Sher Shah Suri, who snatched the Mughal empire from Humayun and ruled between 1538 and 1545, is known for investing in building infrastructure in the shape of the Great Trunk. . Road and the introduction of the rupee as a currency, the development of the postal system, in addition to other efforts to improve administrative capacity. His efforts had a far-reaching impact on increasing India’s productivity and it is for this reason that Humayun, his arch-enemy, called him “Ustad-e-Badshahan” (Master of Kings).

Now, at this current juncture, the Indian government, like Asaf-ud-Daula, must provide immediate relief in the form of expanding the rural employment guarantee scheme and, according to some, the introduction of an employment guarantee scheme. urban, as well as more direct cash. transfers to the poor.

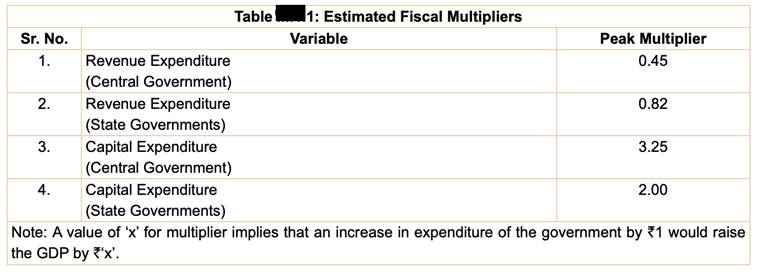

But the multiplier effect of such spending is very small (see Table below; source: RBI). The multiplier effect refers to the factor by which GDP increases when the government spends 1 rupees.

Source: RBI

Source: RBI

To achieve rapid growth at a sustainable rate, India needs the government to invest in increasing the productive capacity of the economy. The multiplier for that is much higher, especially if that capital spending is done by the central government.

As such, apart from the spread of Covid, what will determine the shape and form of India’s economic recovery in the coming weeks and months will be the scope and type of public spending. The government will likely have to adopt a combination of the two policy approaches discussed above.

Stay safe.

Udit

📣 The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay up to date with the latest headlines

For the latest news explained, download the Indian Express app.

© IE Online Media Services Pvt Ltd

.