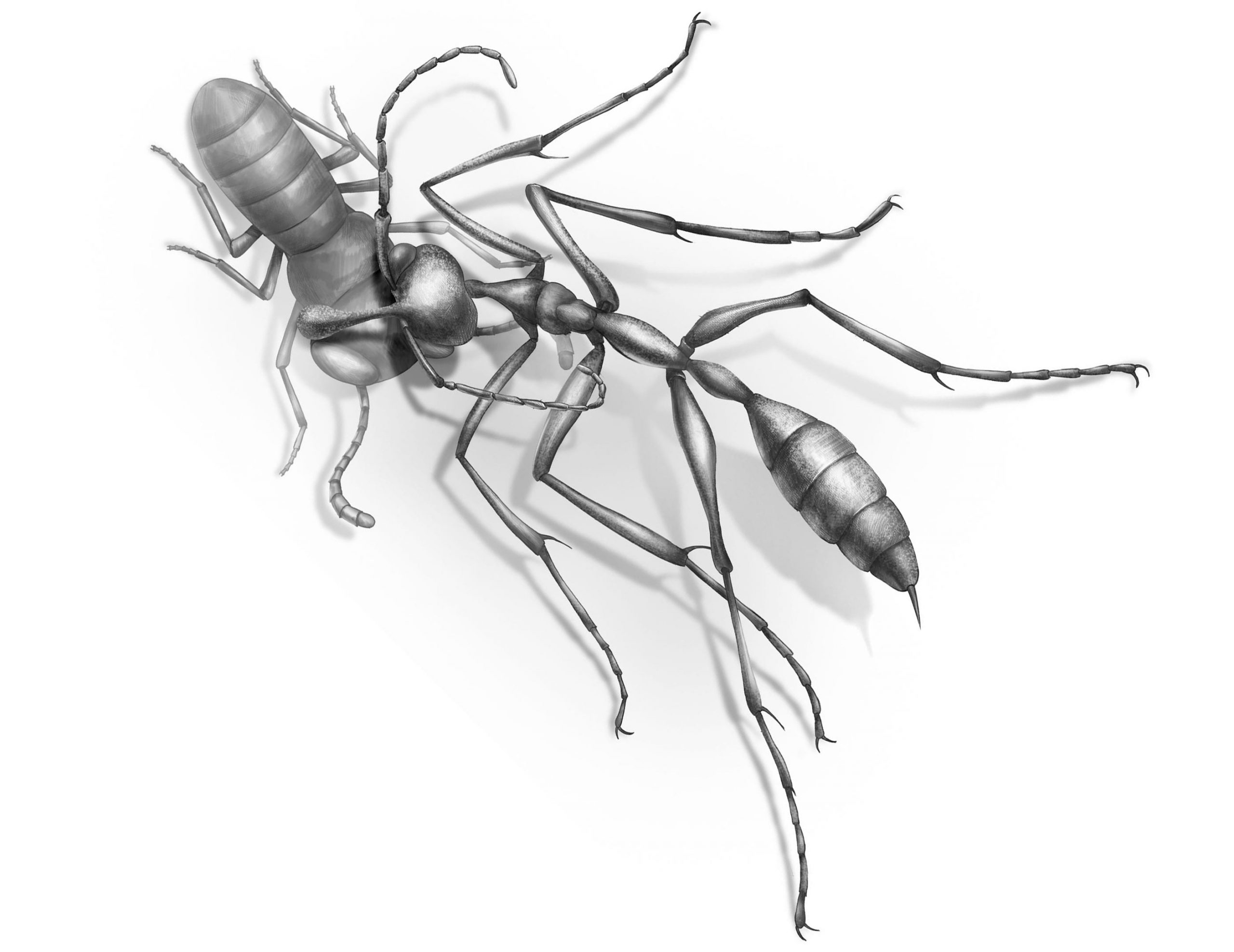

Investigators discover an employee of hell ant Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri who grabs a nymph of Caputoraptor elegans (Alienoptera) preserved in amber dated to ~ 99 Ma. Credit: NJIT, Chinese Academy of Sciences and University of Rennes, France

In a 99-million-year-old preserved amber fossil, researchers get a detailed look at how ‘Hell Ants’ hunt with shear-like mandibles and horn appendages.

In findings published on August 6, 2020, in the journal Current biology, researchers from New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), Chinese Academy of Sciences and University of Rennes in France have preserved a beautiful 99-million-year-old fossil precisely preserved a spiritual insect predator from the Chalk Period – a ‘helmith’ (haidomyrmecine) – because it embraced its unsuspecting final victim, an extinct relative of the cockroach, known as Caputoraptor elegans.

The ancient encounter, trapped in amber returned from Myanmar, offers a detailed look at a newly identified prehistoric species Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri, and presents some of the first direct evidence showing how it and other helmets once used their killer functions – their bizarre snapping but deadly, pain-like mandibles in a vertical motion to torment prey against their horny appendages.

Researchers say that the rare fossil that demonstrates the helmet ant’s feeding mode offers a possible evolutionary explanation for its unusual morphology and highlights a significant difference between some of the earliest ant family and its modern counterparts, which today day uniform mouths have understood by moving laterally together. The hell-ant tribe, along with their striking predatory traits, are thought to have disappeared along with many other early ant groups during periods of ecological change around the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 65 million years ago.

‘Fossilized behavior is very rare, predation especially so. As paleontologists, we speculate about the function of ancient adaptations using available evidence, but to see an extinct predator caught in the act of catching its prey is valuable, “said Phillip Barden, assistant professor at the department. Biological Sciences of NJIT and lead author of the study. ‘This fossil predation confirms our hypothesis for how hell mills work … The only way to catch prey in such a scheme is to keep the ant mills up and down the bottom moves in a direction other than that of all living ants and almost all insects. ”

“Since the first helmet ant was discovered about a hundred years ago, it’s been a mystery why these extinct animals are so distinct from the ants we have today,” Barden added. “This fossil reveals the mechanism behind what we might call an ‘evolutionary experiment’, and although we see several such experiments in the fossil record, we often have no clear picture of the evolutionary path that leads to them.”

Phylogeny and Cephalic homology of half ants and modern lineages. Credit: NJIT, Chinese Academy of Sciences and University of Rennes, France

Driving Diversity of Hell Ants & They Headgear

Barden’s team suggests that adaptations for prey traps probably explain the rich variety of mandibles and horns explained in the 16 species of helmets identified so far. Some taxa with unarmed, elongated horns such as Ceratomyrmex shone prey externally, while other half ants such as Linguamyrmex vladi, or “Vlad the Impaler” discovered by Barden and colleagues in 2017, thought of using a metal-reinforced horn head to impale prey – a feature that potentially used to feed on the internal fluid (hemolymph) of insects.

Barden says that the earliest ancestors of hell ant were first given the opportunity to move their mills vertically. This, in turn, would integrate the mouths and heads functionally in a way that was unique to this extinct tribe.

“Integration is a powerful formative force in evolutionary biology … when anatomical parts first function together, this opens up new evolutionary trajectories as the two functions evolve in concert,” Barden explained. “The consequences of this innovation in mouth-to-mouth movement with the half-ants are remarkable. Although modern ants do not have horns of any kind, some species of helium ants have horns covered with toothed teeth, and others, such as Vlad, are suspected of reinforcing the horn with metal to prevent its own bite from provoking itself. ‘

To further explore, the researchers compared the morphology of the head and mouth part of Ceratomyrmex and several other helmet species (such as head, horn and mandible size) with similar datasets of living and fossil ants. The team also conducted a phylogenetic analysis to reconstruct evolutionary relationships between both Cretaceous and modern ants. The team’s analyzes confirmed that helmets belong to one of the earliest branches of the anti-evolutionary tree and are closely related to each other. Moreover, the relationship between mandible and head morphology is unique in helmets compared to lifelines as a result of their specialized prey-capture behavior. The analyzes also prove that elongated horns evolved twice into half ants.

While the fossil has finally given Barden’s laboratory solid answers about how this long lost class of ant predators functioned and found success for nearly 20 million years, questions remain as to what caused these and other tribes to become extinct while modern ants flourished in the ubiquitous insects we know today. Barden’s team is now trying to describe species from new fossil deposits to learn more about how extinction groups otherwise affect.

“More than 99% of all species that have ever lived are extinct,” Barden said. ‘While our planet is undergoing its sixth mass extinction event, it’s important that we work to understand the extinct diversity and what certain tribal ties may hold while others fall. I think fossil insects are a reminder that even something as ubiquitous and familiar as ants has become extinct. “

Reference: “Specialized predation drives abrupt morphological integration and diversity in the early ants” by Phillip Barden, Vincent Perrichot and Bo Wang, August 6, 2020, Current biology.

DOI: 10.1016 / j.cub.2020.06.106