[ad_1]

Two people travel long distances, one landing at the stop. The next three more. So only one couple has to board to finally empty the bus. In a way, this is what happens with number puzzles.

And statistics surely do not enjoy a better reputation in public life. Sometimes one has the definitive impression that they are blurring instead of revealing the truth, the real.

Just a few recent examples from the last few months:

- Is Hungary really in the middle of international epidemiological statistics right now?

- Now, does the capital have the money to renovate the Chain Bridge or not?

- Is there serious national support for the government and the opposition?

- Does the average Hungarian really pay 260 thousand florins?

- In the end, did we not receive a single penny of additional funding from Brussels for the management of the epidemic?

Apparently these are questions to be decided, yes or no answer.

But the numbers are stubborn.

We stubbornly get into the raspberry when it comes to social issues. They arrive disguised as clarity, posing for clarification, but the coveted order is only promised to continue. Csalfán.

Because in public one, often less is much more, and twice two is five.

How much?

The correct solution to the above questions is yes and no. So, at once.

- In viral terms, we belong to the general midfield globally if we look at the numbers for the whole year, as we very slightly escaped the spring Covid wave. From this, even our current situation can be dramatic.

- Obviously, there is (understand: there is) enough money in the generous capital budget of 400 billion for the renovation of a bridge, but since a number of revenues have been lost, what there is is already tied to something else, practically still no.

- If we add the support of the opposition parties, it really fits with Fidesz. It’s just not certain that this really adds up on Election Day. So there are also the two poles face to face.

- The average salary is also around 260 thousand florins here in Hungary, except that this does not mean the typical Hungarian salary, as it would be the average salary. The “average Hungarian” does not seek the average Hungarian salary, this is the problem.

- The additional EU resources are in the sense in which it has been decided: this money can be reallocated to fight the epidemic. This could not have been done before. They aren’t worth it though, because for the most part we’ve already linked the framework in question here for other purposes.

2,000 trillion HUF versus not a single penny. This is a very broad field of interpretation, let’s face it. where reality does not divide, it does not multiply.

Everyone is right and no one is.

Public numerology

But how is it possible to describe the same situation in so many different ways? Mainly in such a way that the numbers that appear in public life do not reveal every portion of the truth because that is not their function.

They always have a specific persuasion goal.

And given that we live in a diverse society where many different intentions can coexist, it is not surprising that the same data opens different doors of interpretation.

Here you can also think of banal political platitudes like that

Hungary currently has (for the third time) a two-thirds elected government.

Well, no. The government has a two-thirds parliamentary majority, which is certainly not synonymous with two-thirds social support.

But there is also a recurring debate about how many kilometers a highway mayor has renewed. You just have to weigh it and add it up, and then nothing could really be easier! While it is a matter of interpretation, which passages are written with respect to whom.

Who ordered it? Who financed it? Who delivered it?

Now about color inks …

Inferior mathematics is not so valid in the world of politics that there is a separate science and taxonomy of government bubbling macros, just as there are already excellent examples of graph manipulation.

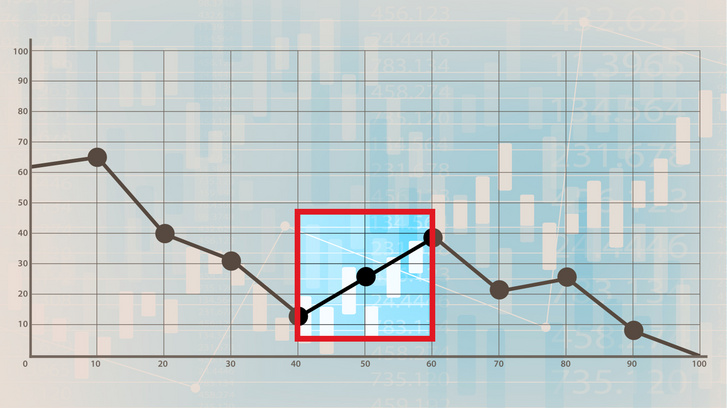

- For example, we can trick steps on the scale to optically flatten a curve. The larger the analysis steps, the smaller the zigzags in the figure.

- We can modify the history so that our numbers look better on paper. This is perhaps the most common pull.

- We can change the context: the same data looks very different in the national / historical comparison than in the international one. So, in fact, we can “prove” anything at any time.

- Or we can get a dramatic jump from any data set as if it were a sign of some more lasting trend (see figure above). So anything can be a result or a failure, that is, at the graphics level.

Furthermore, even most statistically significant changes do not have a significant impact on our daily lives. For example, the amount of the minimum pension in Hungary could increase by as much as 50 percent, even if it does not reach 43,000 HUF. So the thing has no significant meaning (in practical terms: practical meaning).

On the other hand, a “big leap” like a “serious achievement” and a “political success” would be great in a brochure.

It is an illusion of mirage to think, then, that the numbers will put an order to the buzz of political manipulation, and that the ideological debates will end when we finally return to the reality of the data.

We’re so thirsty for stats because most people like to see their ad hoc tweaks confirmed. And while we, as pattern-seeking creatures, roam the data jungle every day, some delight us with indicators from around the world.

[ad_2]