[ad_1]

Although Endre Ady did not acknowledge it, he even said bluntly that Géza Gyóni is not a poet, a real literary historical sensation is the fact that the hitherto unknown poems of the World War I poet were found in a hidden and disused room. from the Krasnoyarsk Museum of Local History.

In addition to Gyóni’s biography and poems, the POWs found a score of manuscript pamphlets, various poems and memorabilia.

As is well known, Géza Gyóni died in 1917 in Krasnoyarsk, at the age of thirty-three, in captivity. He was also buried there, along with his brother.

The 211-page biography you just found was recorded by literary master Lajos Székely, also a prisoner of war, at the Vojennij Gorodok prisoner of war camp near Krasnoyarsk.

At the beginning of his poetic career, Géza Gyóni wrote poems of war propaganda and, later, only mourners of the war. At that time, he did not really belong to the forefront of the Hungarian literary canon, not even to the canon, but due to the mysterious captive circumstances of his early death, his person was always surrounded by a kind of mysterious interest.

Mikhail Semyonovich Batasev, head of the archeology department at the Krasnoyarsk Museum of Local History, told Index that the documents he had just found were completely authentic, as they included text in Russian in addition to Hungarian. Batasev said the find is currently being processed and there are plans to issue a bilingual publication of the documents. And it would be extraordinary if Géza Gyóni’s poems could be published separately.

Gyon’s poems were probably preserved for posterity by Ferenc Dús, a Hungarian anthropologist who works at the Krasnoyarsk Museum of Local History. A rich anno also came to Siberia as a prisoner of war anyway.

The interesting thing about Gyóni’s poems and literary documents is that after the First World War there was an attempt to deliver them to Budapest once, but they could not be delivered. Therefore, the package stayed with the sender.

sixteen

Gallery: Poems by Géza Gyóni found in Siberia

Schweitzer manuscript and other novels

His Hungarian botanical work was also published in Krasnoyarsk – the manuscript of the scientific work of József Schweitzer (1887-1980). According to the informant who informed our newspaper about this, after his release from captivity, József Schweitzer was placed in Arad Catholic primary school, where he taught until his retirement. According to his students, the botanist’s best friend was the microscope and his favorite classrooms were flowers. One of his disciples, after receiving a higher position, visited his teacher to pay his respects. Schweitzer replied, “Well, yes. Yesterday he was another idiot, today he is a colleague. Hello. ”The newly unearthed Hungarian manuscript material also contains seven novels written by Sándor Klein during captivity, as well as drawings, poems, descriptions of the battles of World War I and publications presenting the life of the Hungarians in Krasnoyarsk .

The museum has created a Hungarian-Russian membership foundation to process the documents. According to Batasev, at the same time he contacted the Hungarian embassy in Moscow.

His contemporaries treated him strangely

“Géza Gyóni (Áchim) has never been a poet and never will be. Not a single world war could do that. With a young journalistic sense and in an awkward position, he transposed the forms and states of mind of true poets. It is as much as the author of the war magazine. “

– this can be read in the letter that Endre Ady wrote in 1915 to an unknown young friend.

Géza Gyóni was included in the book So You Write by Frigyes Karinthy. One of the ruthless satirists of the West discovered it in its first stanza:

Their beds barked and the bullets barked,

Ravens over our heads, wait, we have gathered

The cursed Hungarian virtus fought against the great sky

Go Go! … our soul called the horn,

My praying soul trembled these words:

God beat the writers of Pest! “

In 1938, the literary historian Géza Mikola wrote about the poet in the Bulletins of Literary History:

Gyoni has a poem that alone would be enough to immortalize the name of its writer: Caesar, I’m not going. The poem became deservedly famous, the Roman legionist, the lover of life, rebels against Caesar, who orders him to die, and with a single defiant shout he refuses to give his life to Caesar’s conquering rage. Knowing the popularity and tragic end of the Gyoni war, it is understandable that this poem is worthy of, and even provides, an opportunity for much debate.

In his study, András Kispeter (History of Literature, 1985) wrote that Gyóni had difficulty finding his independent voice, but

“A collection of his latest peace poems, The Lover of Life, although not yet free from Ady’s influence, the title itself evokes Ady! -, shows his poetry more and more muscular and intense ”.

And about the poet’s war poems he wrote:

“The war is shown from within, through the eyes of the participant, in his own terrible reality.”

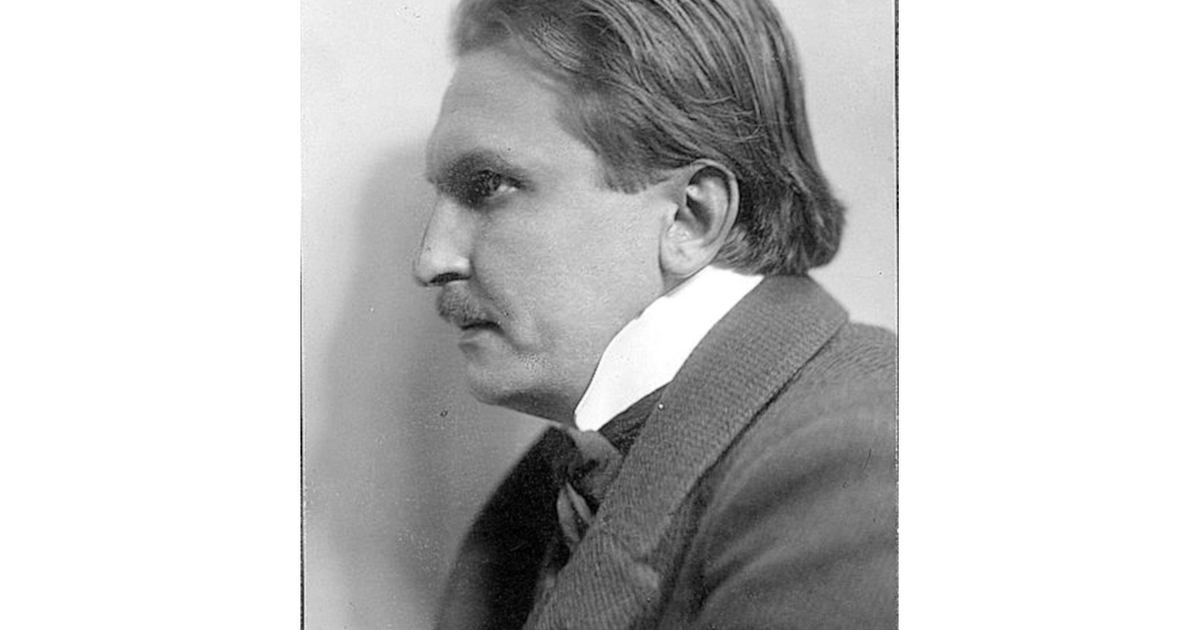

(Cover image:

Gyóni Géza / Wikipedia)

[ad_2]