Fragments of glass-fossilized grass and microscopic traces of plant material, dating to about 200,000 years ago, are all that is left of a Paleolithic hunter-gatherer bed in the back of Border Cave. In the same part of the rock shelter, archaeologists found layers as with more recent (as in at least 43,000 years old) and better preserved leaves of dry grass laid on top, as if people were burning their old, dirty bedding and then laying fresh, clean seas of grass over the ashes – the version of rock protection from changing the leaks.

The findings shed light on an aspect of early human life that we rarely encounter. Most of the artifacts that survive from more than a few thousand years ago are made of stone and bone; even wooden tools are rare. That means we think of the Paleolithic in terms of hard, sharp stone tools and the bones of slaughtered animals. Through that lens, life looks very hard – maybe even harder than it really was. Most of the human experience is lacking in the archaeological record, including comfort for creatures such as soft, clean beds.

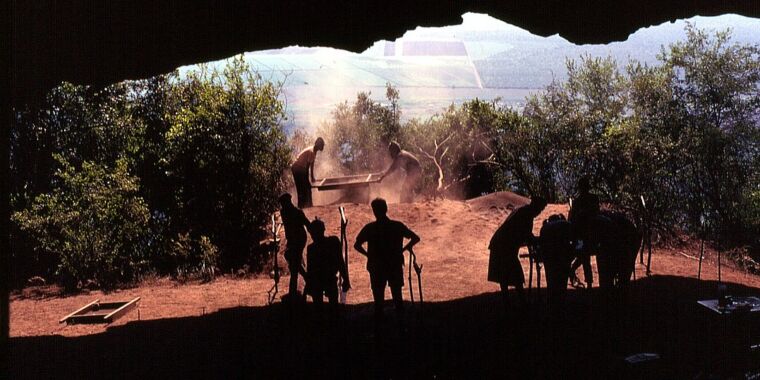

Beds burned

Until now, the oldest bed archaeologists ever found from another South African site called Sibudu, where people 77,000 years ago called layers of grassy wetland plants called seed, mixed with various medicinal plants, and sometimes burned the ancient layers. . Some modern people in parts of Africa also use plants as bedding in similar ways. The Border Cave discovery shows that humans have been making comfortable sleeping pallets out of grass for at least 200,000 years – almost as long as they have Homo sapiens in the world.

-

This dry grass, on top of a layer of ash, is about 43,000 years old.

Wadley et al. 2020

-

These fragments of silicified grass were once a layer of clean bedding, about 200,000 years ago.

Wadley et al. 2020

Using a scanning electron microscope and infrared spectroscopy, paleoanthropologist Lyn Wadley of the University of the Witwatersrand and her colleagues identified the Paleolithic as bed family grass. Panicoideae, which still grow today in the vicinity of Border Cave. The chemical content of the ash below is also well combined with the chemical content of local Panicoideae grass.

Besides being much softer than the cave floor, these old beds were probably surprisingly clean. Burning dirty bedding would have helped cut down on problems with bedbugs, lice, and meat, not to mention unusual odors. Wadley and her colleagues suggest that people at Border Cave even need some extra ash near the heath “to create a clean, odor-regulated base for bedding.”

And charcoal found in the bed layers contains bits of an aromatic camphor bush; some modern African cultures use another closely related camphor forest in their plant bed as an insect repellent. The ashes may have helped, too; Wadley and her colleagues note that “various ethnographies report that ash-blocking insects are descended, which cannot move easily through the fine powder because it blocks their respiratory and biting apparatus and eventually causes them to become dehydrated.”

Work out of bed

However, this does not mean that the beds were always neat and clean. Wadley and her colleagues also found stone flakes and other debris from tool making, which means people probably also used the comfortable stacks of grass as a soft place to sit while working on a new stone tool. For the record, flint button in bed is probably an even lesser idea than eating crackers in bed, but it’s a wonderful human thing to find clues. Grains of red and orange ocher also mixed with the bed layers, and Wadley and her colleagues said the grains probably rubbed off someone’s body art.

This aspect of Paleolithic life sounds at least pleasantly sociable. Imagine that you have just burned your old, sturdy bedding and left a fresh layer of grass saws. They are still spring and soft, and the ashes underneath are still warm. You crouch up and breathe in the delicious scent of camphor, making sure the mosquitoes will sleep you in peace. A fire creeps and jumps nearby, and you stretch your feet toward it to warm your toes. You shove a sharp flake of flint out of the knife you made earlier in the day, and then drift off to sleep.

The next day, of course, you forget to extract those flint flakes from your bedding, and archaeologists will find them 200,000 years later, along with the burnt bits at the end of the grass, where you left it too close to the fire. Good luck living that one down.

Science, 2020 DOI: 10.1126 / science.abc7239 (About DOIs).