Shawn Hayes was grateful that he had been locked up in a city-run hotel for people with COVID-19.

The 20-year-old was not in prison. I wasn’t on the streets chasing drugs. Methadone to treat his opioid addiction was delivered to his door.

Hayes was staying at the hotel due to an outbreak of coronavirus at the 270-bed Kirkbride Center addiction treatment center in Philadelphia, where he had been seeking help.

From early April to early May, 46 patients in Kirkbride tested positive for the virus and were isolated. The facility is now operating at approximately half its capacity due to the pandemic.

Drug rehabilitations across the country have experienced outbreaks of coronavirus or financial difficulties related to COVID-19 that have forced them to close or limit operations. Centers serving the poor have been particularly affected.

Newsletter

Get our free newsletter Coronavirus Today

Sign up to receive the latest news, best stories and what they mean to you, plus answers to your questions.

Occasionally you may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And that has left people with another life-threatening illness, addiction, with fewer opportunities for treatment, while threatening to reverse their recovery gains.

“It is difficult to underestimate the effects of the pandemic in the community with opioid use disorder,” he said. Dr. Caleb Alexander, professor of epidemiology and medicine at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “The pandemic has deeply disrupted drug markets. Normally that would lead more people to treatment. However, treatment is more difficult to achieve. “

Drug rehab is not so much a COVID-19 “tinder “like nursing homesAlexander said, but they are both communal settings where social distancing can be difficult.

Shared spaces, double occupancy rooms, and group therapy are common in renovations. People struggling with addiction are generally younger than nursing home residents, but both populations are vulnerable because they are more likely to have other health conditions, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, which put them at greater risk of having a COVID serious case. -19.

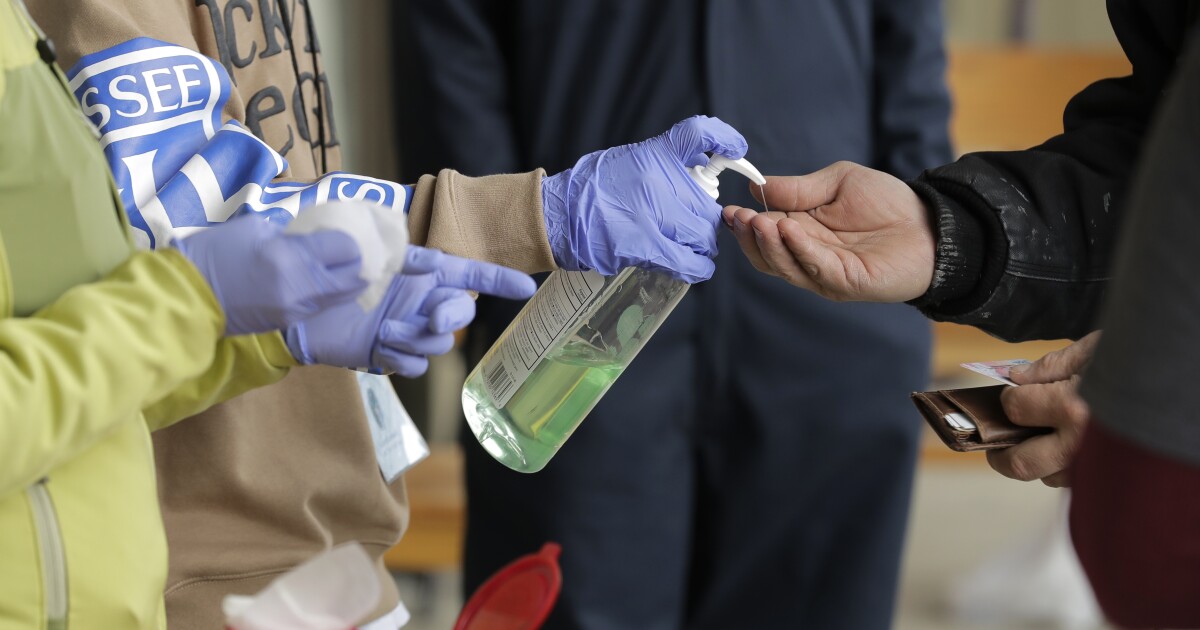

To keep clients safe, some addiction treatment centers employ safety precautions similar to those in hospitals, such as testing all patients who are admitted for COVID-19. Dr. Amesh Adalja, a scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Health Safety Center. But drug rehab must avoid some strategies, like keeping a potentially intoxicating hand sanitizer on the premises.

Adalja said she hopes security measures will make people feel more comfortable seeking help for addiction.

“There will be nothing zero risk, in the absence of a vaccine,” he said. “But this is in a different category than going to a birthday party. She doesn’t want to postpone the necessary medical attention. “

Still, some people who require drug or alcohol rehabilitation have stayed away for fear of contracting COVID-19. Marvin Ventrell, CEO of the National Association. from addiction treatment providers, said many of its roughly 1,000 members saw their patient numbers drop 40-50% in March and April.

Unlike many other centers, Recovery Works, a 42-bed treatment center in Merrillville, Indiana, has seen more clients than normal during the pandemic. The facility had to close for a few days before an alleged COVID-19 case, but reopened after the person tested negative. Since then, he divided his therapy sessions into three groups, staggered meals and banned visits, CEO Thomas Delegatto said.

Then he had an influx of patients.

“I think there are a variety of reasons why,” Delegatto said. “A person who was struggling with a substance use disorder, and who was fired and a nonessential worker, might have seen this as an opportunity to go to treatment without having to explain to their employer why they are taking two, three, four weeks off. “

He also noted that alcohol sales increased Early in the pandemic, when anxiety and isolation increased, and shelter-in-place may have made some families realize that a loved one needs help with an addiction.

Homeless and poor Americans who often live indoors have been particularly prone to the capture of COVID-19, leaving drug rehabilitation dedicated to this population especially vulnerable.

Haymarket Center, a 380-bed sober living and treatment center in Chicago’s West Loop that serves many homeless people, recently had an outbreak of 55 coronavirus cases among clients and staff members.

Two employees tested positive for COVID-19 in late February, but the tests were only available to people showing symptoms, Haymarket President and CEO Dan Lustig said.

Haymarket worked with the nearby Rush University Medical Center to evaluate their clients. Twenty-six men, although asymptomatic, were positive for COVID-19.

The center isolated those patients and eventually moved from double occupancy rooms to single rooms, improved its air filtration system, and changed the way it served food. Now test all new admissions.

“What we discovered was that by doing serial tests we could control the epidemic, not only in Haymarket but throughout the city,” he said. Dr. David Ansell, Rush Senior Vice President of Community Health Equity, who partnered with the city and other health systems in a COVID-19 answer for Chicago’s homeless population.

The economic consequences of the pandemic have also forced some facilities to be reduced. The Salvation Army is closing a handful of its approximately 100 adult rehabilitation centers across the country due to COVID-19-related loss of income. Those renovations were funded by the organization’s resale stores, which were forced to close during requests to stay home.

“Much of what we do depends on donations or items that were donated and then sold in our stores,” said Alberto Rapley, who oversees the business development of the Salvation Army rehabilitation facilities in the Midwest. “When we have financial difficulties, that feels on the other side.”

For example, the Salvation Army drug rehab in Gary, Indiana, which will close in September, treated up to 80 men at a time in its free abstinence-based program. The next closest facility will be in Chicago, more than 30 miles away.

The Kirkbride Center in Philadelphia also serves a largely homeless and low-income population. Dr. Fred Baurer, medical director of the facility, said Kirkbride was “flying blind” at the beginning of the pandemic, with poor testing capacity and personal protective equipment.

On April 8, the first COVID-19 case appeared in the Kirkbride long-term men’s wing. During the following week, six more men in the unit showed symptoms and tested positive, as did 12 of the remaining 22. Holiday Inn Express local.

Kirkbride began requiring face masks, testing all new clients for COVID-19 and banning people in their various units from mixing.

The rehab has been half-filled lately, typically closer to 90% occupancy, in part because it stopped accepting walk-ins and confined new admissions to single rooms.

“I’m starting to feel more confident that we’ve gotten through the worst of this, at least for now,” Baurer said.

Hayes, who recovered from COVID-19 without experiencing any symptoms, was released from the facility to a sober living house last month. He plans to attend 12-step meetings regularly. He hopes to earn his GED and eventually enter the field of mental health.

You recognize the need to stay alert to your recovery now, in a time of greatest anxiety and despair.

“Regardless of the coronavirus or not, the addiction crisis he’s still thereHayes said. “It’s bad. It’s really bad. “

Bruce writes for Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news service covering health topics. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation and is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.