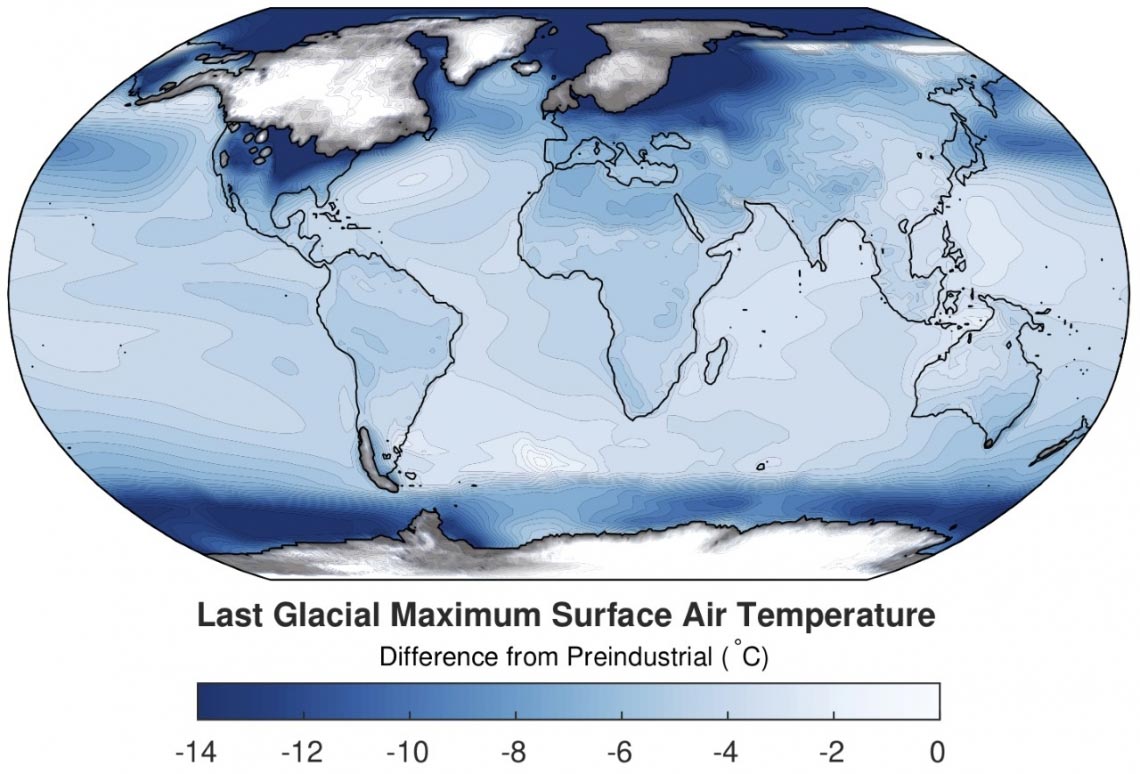

This global map shows the temperature differences compared to pre-industrial times. Dark blue translates to cooler temperatures. The ice sheets of the past are laid on top of the continents. Credit: Jessica Tierney

Scientists’ ice age ‘hindcast’ may shed light on future climate.

A team led by the University of Arizona has raised the temperature of the last ice age – the Last Glacial Maximum of 20,000 years ago – to about 46 degrees Fahrenheit.

Their findings allow climate scientists to better understand the relationship between current rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide – a major greenhouse gas – and average global temperature.

Jessica Tierney. Credit: Jessica Tierney

The Last Glacial Maximum, as LGM, was a frigid period when large glaciers covered about half of North America, Europe and South America and many parts of Asia, while flora and fauna adapted to the cold bloomed.

“We have a lot of data about this time period because it’s been studied for so long,” said Jessica Tierney, a university professor in the University of Arizona’s Department of Earth Sciences. “But one question that science has long answered is simple: how cold was the ice age?”

Tracking temperatures

Tierney is lead author of a paper published today (August 26, 2020) in Nature that found that the average global temperature of the ice age was 6 degrees Celsius (11 F) cooler than today. For context, the average global temperature of the 20th century was 14 C (57 F).

“In your own personal experience it may not sound like a big difference, but actually it’s a huge change,” Tierney said.

She and her team also made maps to illustrate how temperature differences vary in specific regions around the world.

“In North America and Europe, the northernmost parts were covered with ice and were extremely cold. “Even here in Arizona, there was a lot of cooling,” Tierney said. “But the greatest cooling was at high latitudes, such as the Arctic, where it was about 14 C (25 F) colder than today.”

Their findings are in line with scientific understanding of how the Earth’s poles respond to temperature changes.

“Climate models predict that high latitudes will heat up faster than low latitudes,” Tierney said. “When you look at future projections, it’s getting really hot over the Arctic. This is referred to as polar amplification. Similarly, during the LGM we find the reverse pattern. Higher latitudes are just more susceptible to climate change and will continue to do so. ”

Counting carbon

Knowing the temperature of the ice age is important because it is used to calculate climate sensitivity, which means how much the world temperature shifted in response to atmospheric carbon.

Tierney and her team determined that for every doubling of atmospheric carbon, world temperatures should increase by 3.4 C (6.1 F), which is in the middle of the range provided by the latest generation of climate models (1.8 to 5,). 6 C).

Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels during the ice age were about 180 parts per million, which is very low. Before the Industrial Revolution, levels rose to about 280 parts per million, and today they have reached 415 parts per million.

The Paris Agreement did not want to keep global warming above 2.7 F (1.5 C) above pre-industrial levels, but with carbon dioxide levels rising as they are, it would be extremely difficult to exceed 3.6 F (2 C) to prevent) from warming, “Tierney said.” We already have about 2 F (1.1 C) under our belt, but the less hot we get, the better, because the Earth’s system really responds to changes. in carbon dioxide. “

Make a model

Since there were no thermometers during the ice age, Tierney and her team have developed models to translate data collected from ocean plankton fossils into sea surface temperatures. They combine the fossil data with simulations of LGM climate models with a technique called data assimilation, which is used in weather forecasting.

“What happens in a weather bureau is that they measure the temperature, pressure, humidity and use these measurements to update a forecast model and predict the weather,” Tierney said. “Here we use the Boulder, Colorado-based National Center for Atmospheric Research climate model to produce an LGM hindcast, and then we update this hindcast with the actual data to predict what the climate was like.”

In the future, Tierney and her team plan to use the same technique to create warm periods in Earth’s past.

“If we can reconstruct warm climates of the past,” she said, “we can begin to answer important questions about how the earth responds to really high carbon dioxide levels, and improve our understanding of what future climate change may have.”

Reference: “Review of Glacial Cooling and Climate Sensitivity” by Jessica E. Tierney, Jiang Zhu, Jonathan King, Steven B. Malevich, Gregory J. Hakim and Christopher J. Poulsen, August 26, 2020, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-020-2617-x

The research was supported by the Heisings-Simons Foundation and the National Science Foundation.