Worker

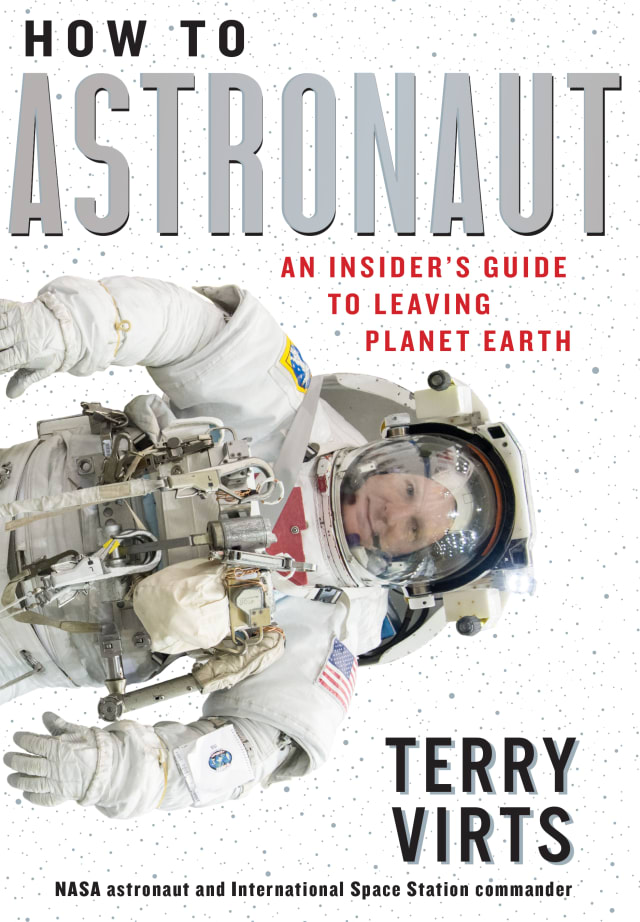

Quotes from How to become an astronaut: An internal guide to leaving planet Earth By Terry Wurtus (Workman). 20 2020.

For all the emergency training as an astronaut, I never expect to be held in the Russian segment of the ISS, to come to the US segment, waiting for my crew and saying with surprise – will the space station be destroyed? Was this the end? When we swam there and thought about our plight, I felt like a person like Lan Lance Morriset singing “Ironic”, who was going down in a plane crash and thinking to himself, “Isn’t this ironic now?” This is how we ended up in that situation.

Each space station crew trains for all sorts of emergencies – computer failures, electrical shorts, equipment malfunctions and more serious fire and air pollution scenarios. However, on the International Space Station, ammonia leaks are the most dangerous. In fact, our NASA trainers were telling us, “If you smell ammonia, don’t worry about running the process, because you’re going to die anyway.” It’s definitely resentment confidence.

A few months after arriving in space, we had a typical day. My Crumate Samantha Christophoretti and I were in each of our crew quarters when the alarm went off, going by email and engaging in administrative work. The sound of an ISS alarm is exactly what you think it should sound like an alarm in the right place – a cross between a Star Trek alarm and a sci-fi B-movie collection. When it closes, there is no doubt that something significant is happening. Sam and I both pulled our heads out of their respective quarters and took a look at the alarm panel.

My first thought when I saw the ATM alarm go off was, “Atmospheric: The atmosphere there should melt.” Occasional air leaks over the fifteen-year history of the ISS sounded the wrong alarm, and I think it should be one of them. However, ATM does not mean that – it is used for toxic environments, mostly from ammonia leaks. Importantly, this alarm was going off for the first time in ISS history. My brain doesn’t believe it, so I said to Samantha, “This is an air leak, right?” To which he immediately replied “No – ammonia leak!”

Pushing towards reality, we jumped into action. Turn on the gas mask. Account for each; We don’t want anyone to be left behind. Float in the Russian segment below ASAP and close the hatch between the US and Russian segments. The US segment uses ammonia as a coolant, but the Russian segment does not, so the air should be safe there. Remove all clothing if contaminated. No one smelled ammonia, so we skipped this step! Close the second hatch

Keep any residual ammonia vapor on the American segment. Ammonia “sniffer” device to ensure that there are no harmful chemicals in the atmosphere in the Russian segment. Everything understood. After that, wait for Houston’s word. . . .

Fifteen long, suspense-filled minutes later, we got the news – it was a false alarm. We let out a collective sigh of relief; The station would not be dead today! Wow. Like the frequent fire alarms and rare air leaks, the Ammonia leak was only added to the collection of ISS false alarms. We put on the ammonia detector, floated back into the US segment, and when that alarm went off we started making a fuss .We started floating in the media.

Then we got an immediate call. “Station, Houston, run ammonia leak emergency inspection, I say again, respond to emergency, leak ammonia, this is not an exercise!” Very clear. Only this time the warning came by radio call, not by electronic alarm. After the false alarm I knew that the military mission of NASA engineers was in control, they were making holes in every piece of data they had, trying to determine if this was a false alarm or a real thing. Now that it has been confirmed by Mission Control that it is a real leak, I have no doubt in my mind that this thing is real. In no way did all those NASA engineers find this call wrong. After working in mission control myself for almost a decade, I had full confidence in our flight director and flight control team. When they said, “Run the ammonia response,” I put on the mask, closed the hatch, and asked questions later.

It was like a scene from a European vacation. Big Ben! ”- or Groundhog Day. Oxygen mask activated – check. U.S. Segment emptied behind someone – without a check. U.S. And closed and sealed the match between the Russian segments – check. Get naked There is no ammonia in the Russian environment – check.

By this point, we were running ISS ammonia leaks twice an hour. We had a quick argument as a crew to discuss how we handled the crisis, what checklist steps were missed, what could have been better and what we needed to report to Houston. By this point, it was very clear that there would be a lot of meetings in Houston and Moscow and everyone in the NASA chain of command would be aware of our plight.

Very quickly the gravity (pun intent) of the situation hits us. The use of ammonia as a coolant for the American half of the ISS has been working well for decades, but we were acutely aware of its dangers. Thankfully, the engineers who built the station did an excellent job of making a leak extremely unlikely, but the possibility was always there. Russian glycol-based coolants, on the other hand, are not dangerous, which is why the entire station crew is safe in the event of an ammonia leak.

The crew was at risk for equipment in addition to the possibility of breathing in toxic fumes. The ISS has two ammonia loops, a series of tanks and pipes that carry heat from the station’s internal water loops to the external radiators. If one ventures out into space, another will be available for cooling equipment. Redundancy will be a serious loss for the station, especially given that there is no longer a space shuttle to re-close the station with the large amount of ammonia tank needed to fill the loop. It would be ugly, but to survive.

Which is not avoidable, although it is leaking from within the ammonia American segment. First, if the full content of the ammonia loop falls inside the station, it will probably push and pop the aluminum structure of one or more modules, as if a balloon had been inflated. Mission control can avoid this problem by moving ammonia into space – we will lose the cooling loop, but it will prevent the station from pinging. Months after returning to Earth, I learned that Houston was seriously considering this option during our crisis, and it was only avoided because of our flight director’s tough and ultimately true-call. That’s why those individuals are paid large sums – they are some of the smartest and most capable people I’ve ever worked with. However, even if you can avoid the catastrophic “ping ping” of the Constitution, the U.S. There will be a problem of ammonia in the segment.

If there was even a small amount of ammonia in the atmosphere, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to remove. The only scrubber we had was our ammonia mask, so theoretically you would allow the astronaut to sit in a contaminated module, breathe contaminated air out and into the mask filter and over time this scrubbing will reduce the concentration of ammonia, but the poor astronaut will clean the air sitting there. It was also covered in ammonia, and assured its fellow crumates in the Russian segment that they would have trouble letting them return to their clean air. It needs to have some kind of shower and cleaning system to clean it completely, which does not exist in space. Soldiers in an atmosphere of chemical warfare or the recent miniseries would have a similar position to Soviet troops in Chernobyl. It is difficult enough to deal with the toxic atmosphere on Earth, but in space it will be almost impossible. The reality is that a real leak in the American segment would render a significant portion of the ISS uninhabitable, and if there were no crew when the equipment broke, there would be no one to fix it.

A real ammonia leak eventually leaked to the U.S. Half of that would lead to the slow death of the ISS, which would later bring the entire station to an end. We knew this and were staring at each other in our afternoons, wondering out loud how long it would be before they sent us home, waiting for the space station to be desolate and prematurely dead.

That evening, we got a call from Houston. “Joking, it was a false alarm.” It was a big false alarm. It turned out that some cosmic radiation had affected the computer, causing it to emit bad data about the cooling system, and it took Houston hours to sort out what was really going on. Because we were told by that call from Houston that it was a real leak, we all assumed it – we know that the people we knew in Mission Control were some of the best engineers in the world and they would be 100 percent sure before making such a call. That. So we were very relieved to get it.