Thirty years after that small step for humanity, Eugene would make his own extraordinary journey to the moon.

This is a story of comets, craters, outer space, and a man who forever changed the night sky. More than anything, it is a love story.

In the summer of 1950 Carolyn Spellmann was a college student living in Chico, California. It was there that she met her future husband and scientific partner, Eugene Shoemaker.

“He became my brother’s best man at his wedding,” Carolyn recalled. “She came there, and I opened the back door, and there was Gene.”

It was love at first sight? “Almost,” Carolyn said.

Chapter 2: Reaching for the Stars

It was Gene who would encourage Carolyn to stand behind a telescope, sparking a lifelong passion and profession.

“Gene just said, ‘Maybe I would like to see things through the telescope,'” Carolyn recalled. “I thought, ‘No, I’ve never stayed up one night in my life, I don’t think so.’ But gradually I fell on the show, at work.”

Carolyn became a celebrated astronomer and even held the Guinness World Record for the largest number of comets discovered by an individual. “That earned me the nickname Ms. Comet,” Carolyn said.

While Carolyn focused her research on near-Earth comets and asteroids, her husband was interested in the things that asteroids created: craters.

“He always thought big, so the origin of the universe was his project,” Carolyn said. “The more we found out he had craters, the more excited he was.”

Chapter 3: shooting the moon

But for Eugene, the moon was always the end goal.

“Gene wanted to go to the moon more than anything since he was a very young man,” Carolyn said. “Gene felt that putting a man on the moon was a step in science … He felt that we had a lot to learn about the origin of the moon and, therefore, of other planets.”

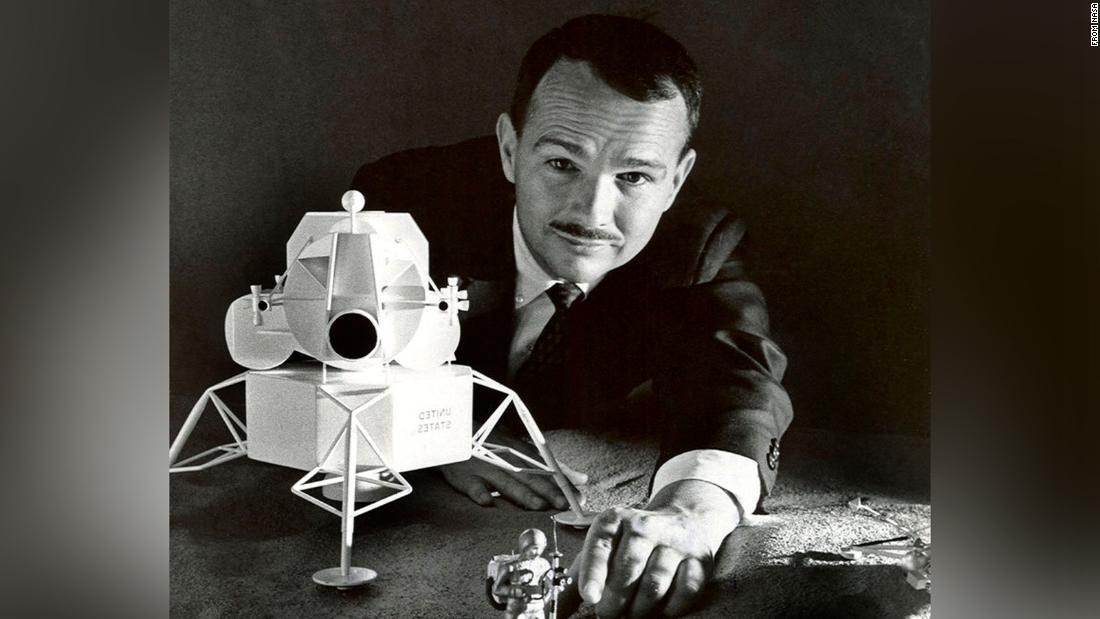

So in 1961, when President John F. Kennedy announced that the United States would send a man to the moon before the end of the decade, Eugene’s life changed forever. As a geologist dedicated to studying craters, he wanted the opportunity to stand on the moon, study its surface with his own hands.

Chapter 4: A Deferred Dream

But it was not his time. A failed medical test stopped his dreams short.

“It was discovered that she had Addison’s disease, which is a failure of the adrenal glands,” Carolyn recalled. “That meant there was no chance that he would ever go to the moon.”

Carolyn said Eugene “felt his target had suddenly disappeared.”

“At the same time, he did not give up.”

Eugene continued to work to bring qualified people to the astronaut training program.

“He helped train Neil Armstrong, he helped train many of the astronauts,” said Carolyn. “He took the first group, and then several other groups to Meteor Crater (in Arizona).”

The meteorite crater was used as a training ground for astronauts because it mimicked the surface of the moon, and both were dotted with meteor-impact craters.

Chapter 5: drawing your attention

While Eugene hid his hope of going to the moon, he and Carolyn set up an observation program at the Palomar Observatory in California, seeking to discover near-Earth objects. That led to one of their biggest discoveries: Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, the comet that collided with Jupiter. It was the first time in history that humans observed a collision between two bodies in the solar system.

“He let go of the dream of going to the moon, he was realistic about it,” Carolyn said. “At the same time, she was still on her mind. When we would do our observation program, she would be looking at the moon with that in mind, I’m sure.”

Eventually Carolyn and Eugene would put space behind them and focus their attention on their own backyard.

“Our focus shifted over the years from looking at the moon to looking only at the sky, to considering what would happen on Earth,” said Carolyn. “Gene had a dream of seeing an asteroid hit Earth.”

Their search for impact craters took them around the world, with a special focus on Australia.

“The trips to Australia were quite special,” said Carolyn. “We went to Australia because it had the oldest available land area to study.”

“We were living outside of our truck … We were able to camp under the stars, which was really special because its sky was just magnificent, and it was different from ours. It was the other way around.”

Chapter 6: A fateful day

On July 18, 1997, Eugene and Carolyn were driving to meet a friend who would help them with some crater maps.

“We were looking into the distance, talking about how good we were having fun, what we were going to do,” Carolyn recalls. “Then suddenly a Land Rover appeared in front of us, and that was it.”

The two vehicles collided and Eugene died.

“I got hurt and I thought, ‘Well, Gene will come as always and rescue me,'” Carolyn recalls. “So I waited, called, and nothing happened.”

Chapter 7: Receive the call

While Carolyn was recovering in the hospital, she received a call from Carolyn Porco, a former Eugene student who had been working on the Lunar Prospector space probe mission with NASA.

“She said, ‘I’m here in Palo Alto with some people who work at Lunar Prospector,'” Carolyn recalls. “They are about to send a mission to the moon, I wonder if you would like to put Gene’s ashes on the moon.”

“

I said, ‘Yes … I think it would be wonderful.’ “

On January 6, 1998, the Lunar Prospector was dispatched, carrying Eugene’s ashes on board. “The whole family was there to fire Gene,” said Carolyn.

Chapter 8: A Revealing Passage

Along with the space probe, an epigraph, laser-engraved on a piece of brass foil, was sent with the remains of Eugene. It included a passage from Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet”.

“And when he dies,

Take it and cut it into little stars

And it will make the face of the sky so beautiful

That everyone will be in love with the night,

And don’t worship the garish sun. “

After completing the Prospector’s mission, he ran out of fuel and crashed into the side of the moon, next to the South Pole. The impact created its own crater, and that’s where Eugene’s ashes remain today.

“Gene spent most of his life thinking about craters, about the moon,” said Carolyn. “It was ironic that she ended her life with the moon too … but she would have loved to know what happened.”

Epilogue

A few years before his death, while receiving the William Bowie Medal for his contributions to geophysics, Eugene noted that “not going to the moon and hitting it with my own hammer has been my biggest disappointment in life.”

“But then, he probably wouldn’t have gone to the Palomar Observatory to take about 25,000 movies of the night sky with Carolyn,” he continued. “We wouldn’t have had the thrill of finding those fun things that collide at night.”

Carolyn always misses him. To this day, she will look up at the moon and imagine it there with its rocks, looking down.

Hearing her say it, he still lights up each of his night skies.

Correction: An earlier version of this story wrongly expressed the number of astronauts who first landed on the moon. There were two, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

.