[ad_1]

In a tragedy reminiscent of Romeo and Juliet, a couple in Nigeria committed suicide earlier this month after their parents forbade them to marry because one of them was the descendant of slaves.

“They say we can’t get married … all because of an ancient belief,” read the note they left.

The lovers, who were in their early 30s, hailed from Okija, in the southeastern state of Anambra, where slavery was officially abolished in the early 1900s, as in the rest of the country, by the United Kingdom, the colonial ruler of Nigeria. at that moment.

But the descendants of freed slaves among the Igbo ethnic group still inherit the status of their ancestors, and local culture prohibits them from marrying those Igbos considered “free-born.”

“God created everyone equally, so why would humans discriminate just because of ignorance of our ancestors?” The couple said.

Many Igbo couples encounter such unexpected discrimination.

Three years ago, 35-year-old Favor, who prefers not to use her last name, was preparing for her wedding to a man she had dated for five years, when her Igbo family discovered that he was the descendant of a slave.

“They told their son that they didn’t want anything to do with me,” said Favor, who is also Igbo.

At first, her fiancé was defiant, but pressure from his parents and siblings soon exhausted him and ended their romance. I felt bad. I was so hurt. It hurt so much, ”he said.

Prosperous but ‘inferior’

Marriage is not the only barrier faced by descendants of slaves.

They are also banned from holding traditional leadership positions and elite groups, and are often barred from running for political office and representing their communities in parliament.

However, education or economic advancement is not impeded.

Ostracism often pushed them to more quickly embrace Christianity and the formal education brought by the missionaries, at a time when other locals were still suspicious of foreigners.

Some descendants of slaves are among the most prosperous in their communities today, but no matter how much they achieve, they are still treated as inferior.

In 2017, Oge Maduagwu, 44, founded the Initiative for the Eradication of Traditional and Cultural Stigmatization in our Society (Ifetacsios).

For the past three years, he has been traveling through the five southeastern states of Nigeria, advocating for equal rights for descendants of slaves.

“The kind of suffering that blacks are going through in America, descendants of slaves here are going through the same thing, too,” he said.

Maduagwu is not a descendant of slaves, but she observed inequality growing up in Imo State and was driven to address it after seeing the devastation of her close friend who was prevented from marrying a descendant of slaves.

During her travels, Ms. Maduagwu meets separately with traditional people of influence and descendants of slaves, and then mediates in dialogue sessions between the two groups.

“The men sat down to make these rules,” he said. “We can also sit down and redo the rules.

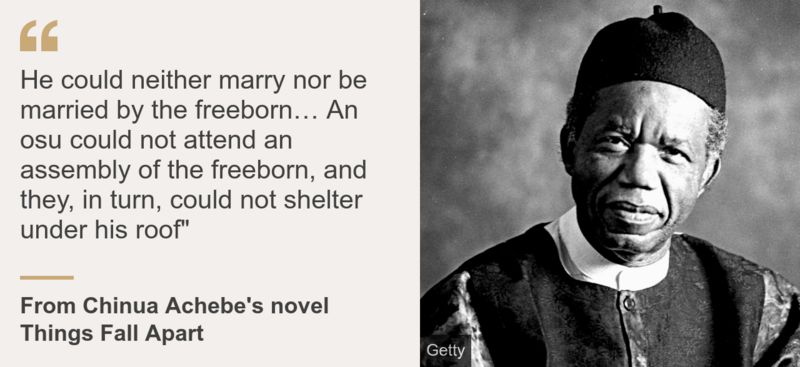

“The descendants of slaves among the Igbo fall into two main categories, the Ohu and the Osu.

The ancestors of the ohu were owned by humans, while those of the osu were owned by the people of the gods dedicated to community shrines.

“Osu is worse than slavery,” said Ugo Nwokeji, a professor of African studies at the University of California, Berkeley, who believes missionaries misclassified the osu as slaves.

“Slaves could transcend slavery and become slave owners themselves, but the osu for generations to be born could never transcend that.”

Discrimination against USO tends to be worse.

While the ohu are marginalized as outsiders, with no known places of origin or eternal ties to the lands where their ancestors were brought as slaves, breaking taboos on relationships with the osu is accompanied, not only by fear of social stigma. , but to the punishment of the gods who supposedly possess them.

Her father told Favor’s fiancé that his life would be cut short if he married her, an osu.

“They instilled fear in him,” he said. “She asked me if I wanted her to die.”

‘Grassroots commitment’

Such fears have made it difficult to enforce anti-discrimination laws that exist in the Nigerian constitution, in addition to a 1956 law by Igbo legislators that specifically prohibits discrimination against ohu or osu.

“Legal prohibitions are not enough to abolish certain primordial customs,” said a Catholic archbishop in Imo state, Anthony Obinna, who advocates an end to discrimination.

“You need more grassroots participation.”

In her defense, Ms Maduagwu educates people on the various ways in which traditional guidelines on relationship with the USO have been violated, “without the gods wreaking havoc.”

“Today we are tenants of their houses, we are on their payroll, we are going to borrow money from them,” he said.

Such an association with the USO would have been unthinkable in the past.

There are no official data on the number of descendants of slaves in southeastern Nigeria.

People tend to hide their status, although this is impossible in smaller communities where everyone’s lineage is known.

Some communities only have ohu or osu, while others have both.

In recent years, the growing turmoil of ohu and osu has led to conflict and unrest in many communities.

Some descendants of slaves have started parallel societies with their own leadership and elite groups.