[ad_1]

“So dear to all our hearts is the glorious name of our General; our beloved Kim Il Sung of eternal fame, ”reads the lyrics to one of North Korea’s best-known songs,“ Song of General Kim Il Sung, ”which honors the country’s founding ruler and eternal president.

“Tell the blizzards burning in the wild plains of Manchuria,” he continues. “Tell me, nights in deep forests where silence reigns.”

It’s a triumphant march song that ethnomusicologist Keith Howard has heard countless times since he first visited North Korea in 1992.

Universally known throughout the country, it is played on the news and is sung by schoolchildren. Howard even saw the lyrics etched into the rocks along the mountain trails to inspire hikers.

“It really establishes who Kim Il Sung is and celebrates him as the person who fought the Japanese single-handed and then got rid of them, which is the authoritative image of what happened,” said Howard, a professor at London’s School of Oriental Studies. and Africans, in a telephone interview.

“It is much more important than the national anthem, because the national anthem is essentially what you play for foreigners, whereas this is what you sing in (North) Korea.”

Despite spending years of research on the musical traditions of the hermit kingdom, Howard admitted that his job involves listening to an inordinate number of “mind-numbing” songs that “you probably wouldn’t want to listen to for more than five minutes.”

But his new book “Songs for ‘Great Leaders'” is not simply a study of music, dance and instruments, it is an exploration of how they reflect and reinforce the ideology of the state.

If, as Howard’s book suggests, North Korea “behaves as if its entire territory is a theater,” then it is alive with song and dance.

And given the country’s strict control over creativity, they are used almost exclusively as instruments of propaganda, from the country’s “mass games”, in which thousands of people act in perfect unison, to school classrooms, where students are taught. children a repertoire of approved songs from an early age.

The evolving role of music

It’s a story that the British professor dates back to the 1930s, when Korea was still under Japanese rule.

In addition to introducing new styles of music, Japan dominated the East Asian recording industry, and professional musicians from Korea often had to travel to studios in Tokyo and Kyoto in order to record.

It was also around this time that communist guerrillas, who resisted colonial rule, began to adapt, and often directly copy, songs from other revolutionary groups in the region.

“North Korea would deny this and say that the revolutionary songs were totally independent and written by people close to Kim Il Sung,” Howard said. “But they all, to us, sound exactly the same as the equivalents of China or the Soviet Union.”

When Kim Il Sung, the grandfather of the current leader, Kim Jong Un, took power in 1948 after the division of Korea, he set out to reshape its artistic traditions.

In a 1955 speech, he said that his country “had not taken steps for a systematic study of the history and national culture of our country” and called for “every effort to be made to unearth our national legacies and carry them forward. “

Rather than creating new state songs from scratch, Kim sent musicologists into the field to document popular music and poems already known to many people.

Despite millennia of shared culture on the Korean peninsula, Kim prioritized songs that originated in the north. He then ordered that they be reformulated using socialist themes, their lyrics rewritten to serve political ends.

By the late 1960s, the then-young son of the leader, Kim Jong Il, had “taken over the reins of art production,” Howard explained.

This period saw the arts play an increasingly important role in building national identity, with new operas, cantatas, and theater productions narrating and glorifying the country’s past.

Chief among them are the so-called Five Great Revolutionary Operas, which offer a revisionist view of North Korean history, along with communist messages and celebrations from the country’s leaders.

The first of them, “The Sea of Blood” from 1971, tells the story of a peasant woman who overcomes Japanese brutality before joining the guerrilla struggle against her oppressors. Meanwhile, “The Flower Girl” traces the struggles of an indebted family with a ruthless landowner, in a harsh critique of pre-communist feudalism.

These productions “enshrine everything you are supposed to know” about the grassroots of the country, Howard said. “They’re pretty dark in terms of lighting and (plots), all the way. Then, in the last 10 minutes, there is a section where everything becomes light, and it is the light of Kim Il Sung who has triumphed and rebuilt Korea. “

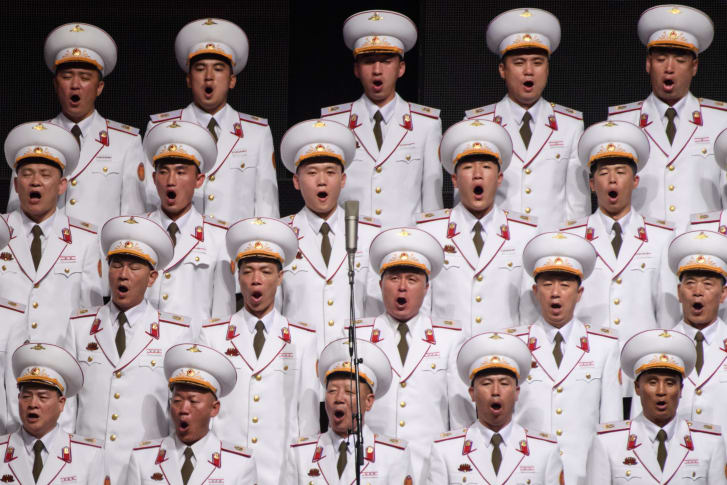

Kim Jong Il, who ruled North Korea after his father’s death in 1994, is also responsible for expanding the country’s massive shows – highly choreographed performances involving tens of thousands of singers, dancers, and gymnasts.

Usually staged in the world’s largest stadium, Pyongyang’s May Day Stadium, the shows tell the story of North Korea in a stunning display of color and coordination.

But beyond the obvious, shows promote collectivism in invisible ways, explained Howard, who said the choreography is often “deliberately complicated.”

“It could be a lot easier,” he said. “(But the routines) get complicated to the point that if one person goes wrong, the whole team, the whole setup, will collapse.”

As Kim Jong Il himself told the producers of mass performances in 1987, “Schoolchildren, aware that a single slip in their action can spoil their mass gymnastic performance, do their best to subordinate all their thoughts and actions to the collective.” .

Musical monopoly

The idea that an authoritarian regime can use music and dance as tools is not new.

After all, almost all societies institutionalize songs that evoke shared values, national myths and historical events, from “The Star-Spangled Banner” to “London Bridge is Falling Down.”

But North Korea’s monopoly on creative expression makes the state’s songs, and therefore its approved messages, unique.

“There is no evidence that people are creating their own music outside of what is centrally allowed,” Howard said. “The only record company is state-owned and there are no performances that are allowed outside of what is authorized.”

You don’t even have the right to create new words (for existing songs), and if you did, you would have to be incredibly careful, because if they were deemed inappropriate you would be in trouble.

“The government’s approach to music seems to have evolved in recent years. North Korea’s first contemporary girl group, Moranbong Band, debuted in 2012, a year after the current leader, Kim Jong Un, became supreme leader.

Perhaps influenced by the illicit arrival of South Korean pop culture (smuggled in on DVDs or, more recently, USB sticks), the band offers something comparatively contemporary.

Its members wear makeup and dress “slightly provocatively,” as Howard put it.

They are also shown using instruments made by brands like Yamaha and Roland, while pop predecessors like the Pochonbo Electronic Ensemble (which, in the 1980s, became the first group in the country to use electric guitars and synthesizers) had logos of hidden or eliminated capitalist countries.

However, the lyrical content remains the same. Moranbong Band may sound like the North’s answer to K-pop, but their songs still focus on praising the country’s leadership and military achievements.

Such strict controls mean that, as a rule, North Korean music makes listening repetitive, Howard said. State-sanctioned songs, even to someone with a deep understanding of their context, arrangements, and instrumentation, can end up sounding very similar.

However, the variety is in the ear of the beholder. It is a point that the ethnomusicologist demonstrated with an anecdote of a trip to North Korea in which he complained to his government caretaker about the “boring” music that was heard every day in his car.

“The guide said, ‘Ooh, I’ll bring you something completely different tomorrow,” Howard recalled. “The next day he arrived with two cassettes of children’s songs. But it was just children singing the adult songs, exactly the same, but done by children. “

Then we had a fascinating discussion in which he tried to persuade me that they were totally different. “