[ad_1]

For the past year, workers have been busy transforming a disused parcel of land down the hill from the office of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed into a park displaying their political vision.

The 48-hectare Friendship Square is rich in symbolism that promotes unity: a fountain is timed to the patriotic hit song “Ethiopia” and a raised platform for speakers is flanked by 76 araucaria trees, one for each ethnic group represented. in the upper house of parliament.

However, a year after Abiy won the Nobel Peace Prize, there is growing concern that this message of unity sounds empty.

Shocking inter-ethnic violence persists, especially in the Oromia region, the home of Abiy.

Police and soldiers increasingly resort to deadly force against protesters.

And several opposition leaders have been jailed on terrorism charges, putting into question whether the historic elections scheduled for next year will represent a true break with Ethiopia’s authoritarian past.

Amid the turbulence, Abiy has paid close attention to Friendship Square, often visiting the site late at night to assess progress, according to his aides.

The Nobel Prize judges celebrated Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s push for peace with Eritrea. By Fredrik VARFJELL (AFP / Archive)

The Nobel Prize judges celebrated Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s push for peace with Eritrea. By Fredrik VARFJELL (AFP / Archive) Its press secretary, Billene Seyoum, told AFP that the park and other beautification sites in Addis Ababa are “representations of how quickly we can get involved in projects, turn them around and hand them over for public use.”

That approach, however, echoes former Ethiopian leaders who were quick to put their stamp on the capital, pushing other voices aside, said Biruk Terrefe, an Oxford researcher who has studied Abiy’s development ambitions.

“The decision making around these urban projects has been reminiscent of past administrations. Many of the city’s urban planners were marginalized.”

Upset at home

Abiy was appointed prime minister in 2018 after years of anti-government protests, and his 2019 Nobel Prize appeared to briefly revive the “Abiymania” of his first months in office.

But two weeks later, security problems began to resurface.

Jawar Mohammed, a former media mogul and Abiy ally, accused the government of trying to orchestrate an attack against him.

The government recently opened Entoto Park, a sprawling complex in the Addis Ababa hills complete with a spa, glamping tents, stables and a go-kart track. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP)

The government recently opened Entoto Park, a sprawling complex in the Addis Ababa hills complete with a spa, glamping tents, stables and a go-kart track. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP) The claim sparked protests against Abiy in Addis Ababa that escalated into inter-ethnic violence and left scores of people dead across Oromia.

The incident highlighted divisions between Abiy, Ethiopia’s first Oromo leader, and Oromo nationalists like Jawar, who say the prime minister is a poor defender of their interests.

More recently, Oromo pop star Hachalu Hundessa was shot dead in June, sparking further riots that claimed more than 160 lives in Oromia and Addis Ababa.

More than 9,000 people were detained in mass arrests, including opposition leaders such as Jawar and Bekele Gerba.

His supporters took to the streets to report his arrests, prompting security forces to clamp down, with deaths reported in 13 locations in Oromia over a series of just a few days in August, according to the Human Rights Commission of Ethiopia.

A stalled peace process

The Nobel chiefly honored Abiy’s push for peace with neighboring Eritrea, which had been a sworn enemy of Ethiopia since a brutal border war broke out in 1998.

Abiy maintains warm public relations with Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, but attempts to exploit his rapprochement have been complicated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), which dominated Ethiopian politics before Abiy and remains in command. in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia.

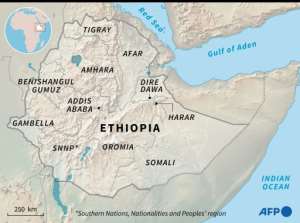

Regions of Ethiopia. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP)

Regions of Ethiopia. By Simon MALFATTO (AFP) Long hostile towards Isaías, TPLF leaders are now also openly fighting with Abiy, complaining that his government has made them a scapegoat for all the country’s troubles.

The dispute reached a new low last month when Tigray went ahead with regional elections, ignoring a federal decision to postpone all voting due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Tigrayan officials say they now view Abiy, whose term would have expired this week if lawmakers hadn’t extended it due to the pandemic, as an illegitimate leader.

Safety remains a priority

These divisions aside, Abiy continues to uphold her “Medemer” (Amharic for synergy) philosophy spelled out in a 2019 book and sees beautification and development projects as an important way to do so.

Tigray went ahead with its regional elections, ignoring a federal decision to postpone all voting due to the coronavirus pandemic. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP / Archive)

Tigray went ahead with its regional elections, ignoring a federal decision to postpone all voting due to the coronavirus pandemic. By EDUARDO SOTERAS (AFP / Archive) In addition to Friendship Square, his government recently opened Entoto Park, a sprawling complex in the Addis Ababa hills complete with a spa, glamping tents, stables and a go-kart track, as well as restaurants and jogging and walking trails. bicycle.

Foreign tourists are an obvious target for projects in Addis Ababa, but authorities say all Ethiopians will benefit, while pointing to additional projects planned outside the capital.

Billene, Abiy’s press secretary, rejected claims by opposition politicians that the projects were a distraction from Ethiopia’s political and security problems.

“Nobody said it is a priority over human security, over the rule of law,” he said. “These are things that are being done in parallel.”

Lately, state media has shown footage of the drone projects on top of the evening news.

Whether the Ethiopians are on board is an open question.

“It is difficult to know what the public’s position is on these projects,” Biruk said.

“I guess that’s what elections are for. Voters decide.”