[ad_1]

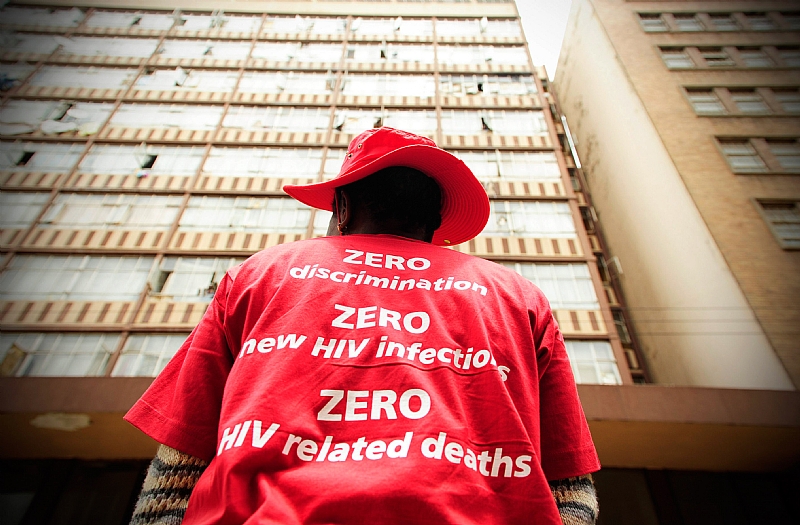

Since 2013, global efforts have been made to control the AIDS epidemic by 2020 through the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. The goal has been for 90% of all people living with HIV to know their status; and of them, 90% started antiretroviral treatment (ART); and of these, 90% achieve viral suppression through adherence to ART. Viral suppression means that the virus in their blood is undetectable and they cannot transmit HIV sexually.

Much progress has been made in achieving these goals. To date, 14 countries have reached the 90-90-90 targets. However, missed targets in other countries have led to 3.5 million HIV infections and 820,000 AIDS-related deaths since 2015.

One of the countries that missed is South Africa, which bears 20% of the global burden of HIV. By 2018, it is encouraging that 90% of all people with HIV in South Africa knew their status. However, only 68% of those who knew their status received ART; and of them, 87% were suppressed virally. This equates to 61% of all people living with HIV in South Africa starting sustained ART and 53% of all people living with HIV viral suppression.

Then in late 2019, COVID-19 emerged and has now spread around the world. This new pandemic has changed the projected course of public health resources and existing campaigns against HIV. The South African National AIDS Council is concerned that progress on multi-year strategic plans has been disrupted. This is a concern shared by many countries with a high burden of HIV.

COVID-19 has put pressure on the country’s health system, which is already under stress. Steps taken to curb the spread have made it difficult for people to access routine medical care and medicines for chronic non-communicable diseases and HIV. Strategies are needed to optimize health-related outcomes for all conditions while allowing the health system to combat the new pandemic.

COVID-19 and health systems

Tough national lockdowns around the world, including that of South Africa, were essential in slowing down the transmission of COVID-19 and allowing health systems to prepare for the impending wave of critically ill patients.

Unfortunately, these unprecedented closures across the country have had subsequent effects on other aspects of public health systems. They have created a serious threat to countries with high HIV prevalence. People who depend on HIV prevention, care and treatment services have become even more vulnerable.

People with HIV need ART to survive, because there is no cure or vaccine. During the confinement, patients were afraid to leave their homes to collect medicine. The concern was sparked by fear of contracting COVID-19, but also by the threat of police brutality or incarceration through the enforcement of quarantine. For patients arriving at ART clinics, many facilities experienced, and are still experiencing, deficiencies in supply chain management that lead to medicine stockouts. Additionally, due to the influx of COVID-19 patients, other services (such as reproductive health services) may not have been available.

The World Health Organization and UNAIDS projected that a complete six-month interruption of HIV treatment could lead to an excess of more than 500,000 AIDS-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa over the next year. This is a big step backwards. In 2018, 470,000 AIDS-related deaths were reported in the region.

South Africa has one of the highest numbers of HIV cases and people on ART. The country would experience the greatest changes in both HIV incidence and mortality due to ART interruptions. Treatment interruptions or delays will further compromise the immune systems of people with HIV. This could mean that the disease progresses to where the CD4 count is too low to be reconstituted or opportunistic infections become unmanageable.

These projections should scare everyone. As it stands, as of April 2020, 36 countries containing 45% of the world’s ART patient population have reported interruptions in ART provision. Twenty-four countries are fighting shortages of first-line treatment regimens. Other by-products of a disrupted healthcare system are that 38 countries reported a substantial decline in uptake of HIV tests.

South Africa is already experiencing a nearly 20% decline in ART collection in key provinces and a 10% decline in viral load testing of ART patients since the introduction of the blockade in March. Even shorter and sporadic treatment interruptions can lead to additional complications. These include an increase in the spread of resistance to HIV drugs, which has long-term consequences for the success of treatment in the future.

HIV and COVID-19

Globally, scientists have focused primarily on the increased risk of COVID-19-related disease and death associated with non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes.

Unfortunately, the role that other infectious diseases play in health-related outcomes is largely forgotten. The successes of established HIV programs make people with HIV even more vulnerable to adverse health events. Therefore, it is also important to understand that this same population is at increased risk for COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality.

There is an intersection between noncommunicable diseases and infectious diseases, with HIV at the center. The nature of the virus and the treatment required means that people with HIV are at increased risk of inflammation and disease from metabolic syndrome. This puts them at risk for chronic non-communicable diseases, a risk factor for COVID-19. Additionally, ART has allowed people with HIV to live longer and naturally develop these comorbidities as they age. People with active tuberculosis (TB) are 2.5 times more likely to die from COVID-19. In South Africa, the TB / HIV co-infection rate is over 60%.

The first published study on the effect of COVID-19 infection among people with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa was reported in the Western Cape, South Africa. People with HIV have a 2.75 times greater risk of dying from COVID-19 than those without HIV. Viral suppression did not appear to affect health outcomes, and HIV accounted for about 8% of all COVID-related deaths. There is greater cause for concern when considering the high levels of comorbidity of HIV with noncommunicable diseases and tuberculosis.

Way forward

The projected models must be taken seriously and strategies are required to maintain all vital health services.

There is an urgent need for differentiated service delivery globally and locally to ensure continuity of HIV service (the most critical and uninterrupted supply of ART) during the COVID-19 pandemic. These strategies could include a change in where HIV tests are done and treatment is delivered. Patients may receive longer refills or bulk treatment packages.

Community services could help both pandemics. This strategy could ease pressure on public toilet facilities while protecting the most vulnerable populations who need to stay at home to minimize the risk of exposure.

With the restricted global movement comes restricted imports of HIV testing and treatment. Countries should include locally manufactured drugs in their national ART regimens. Governments, providers, and donors must prevent excess HIV-related deaths by creating an uninterrupted supply of ART.

If the world is single-minded and focuses exclusively on fighting a pandemic (COVID-19), forgetting others, the effects of other morbidity and mortality on health systems will be seen for a long time.

Kathryn L Hopkins is affiliated with the Perinatal HIV Research Unit, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Glenda Gray receives funding from the NIH for HIV vaccine research and is an employee of the SAMRC.

By Kathryn L Hopkins, Perinatal HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand and

Glenda Gray, Research Professor, Perinatal HIV Research Unit and President of the South African Medical Research Council![]()