One of the clichés of rock, originating from a letter from the Neil Young song, is that “it is better to burn than to fade away”. And indeed, many of his most famous victims, from Jimi Hendrix to Kurt Cobain, left the stage suddenly and surprisingly thanks to the tragic premature deaths. But even those whose play was long, after a brief initial explosion, can leave a strong legacy.

Such was the case of Peter Green, founder of Fleetwood Mac, who passed away on July 25 at the age of 73, leaving an indelible mark on generations of guitarists based mainly on a central body of work between 1966 and 1970.

Born as Peter Greenbaum in 1946, the youngest son of an East End Jewish family and, like many of his generation, paralyzed by imported American blues records, he emerged just after the initial wave of British guitar heroes from blues-rock, especially the famous triumvirate of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.

He made his name by filling Clapton’s shoes in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, a kind of academy and clearinghouse for many who would go on to some of the greatest rock acts of the decades to come. Having replaced Clapton at the occasional concert, Green took a place in the band when Clapton left to form Cream. Green, in turn, would be replaced in the band by Mick Taylor, before Taylor joined the Rolling Stones in 1969.

Replacing Clapton was a daunting task for Green. Clapton’s fan base among London blues fans was vocal, famous for the “Clapton is God” graffiti that appeared on a London wall at the time.

However, Green was up to the challenge, stamping his mark on Bluesbreakers’ next album, A Hard Road (1967), both as a singer, and with instrumental compositions like The Supernatural that established him as an eminent instrumentalist in his own right.

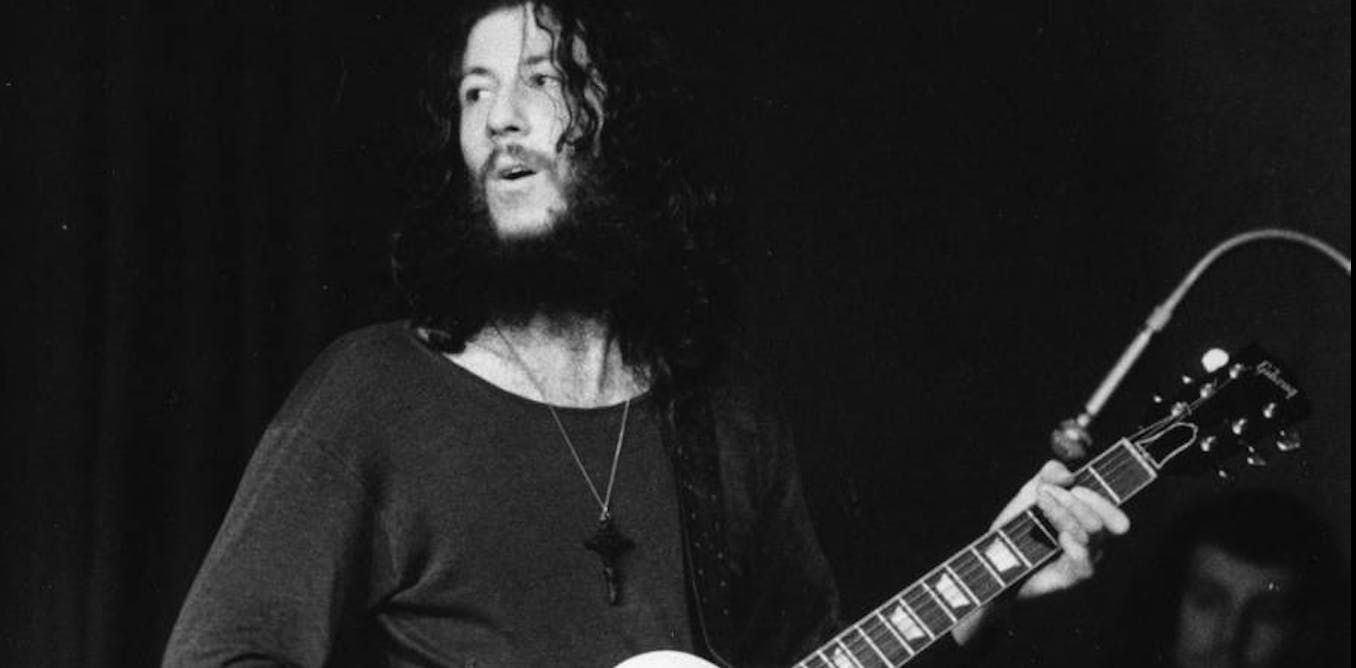

PA / PA Wire / PA Images

Importantly, he did this away from the overt virtuosity of the other guitar heroes of the time. As Mick Fleetwood would say:

It was immediately because of the human touch, and that’s what Peter’s game has represented to millions of people: He played with the human, not the superstar touch.

Forming Fleetwood Mac

A key tension within Green’s career, and his personality, was between ambition and independence, on the one hand, and shyness and fragility on the other. This was made clear when, eager to establish his own group, he parted ways with the Bluesbreakers after an album, taking drummer Mick Fleetwood and later bassist John McVie with him, but naming the new band Fleetwood Mac after his rhythm section and sharing leadership. guitar and voice duties with new recruit Jeremy Spencer.

In this new outfit, her ability to innovate stood out. A series of successes built on his growing confidence as a composer and pushed the limits of the blues. Others, including Clapton, fueled the role of the “guitar hero” through increasingly lengthy exposures of fingerboard prowess. But Green, despite his technical ability, focused on the nebulous merits of “feel” and “tone,” and ultimately made these indispensable facets of the rock guitar arsenal. He would remember

Playing fast is something I used to do with John Mayall when things were not going very well. But it is not good. I like to play slowly and feel every note.

A journey far away

Her brief comparative stay with Fleetwood Mac yielded standards that include Oh Well! (which inspired Led Zeppelin’s Black Dog) and Black Magic Woman, later an author song for Santana.

But in his songs, the fragility of The Green Manalishi (With the crown of two points), its precursor sound density of heavy metal, and the uncertainty of the Man of the world, evidenced a growing concern that would collapse his career. On tour in 1970, after an LSD trip to a commune in Germany, one of several he took, he abruptly left the band, unable to cope with his growing fame.

Fleetwood Mac would spend the next few years with a rapidly spinning lineup, including a brief return from Green to help them complete a tour after Jeremy Spencer left to join a sect. They moved to the United States and, after recruiting Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, delivered one of the defining albums of the 1970s: the hugely successful rumors.

Green himself fought. Like Pink Floyd founder Syd Barrett, whose band achieved stratospheric success after his own mental illness exacerbated by LSD precipitated his departure, Green made occasional recordings in the early 1970s, but never found his balance.

Later, diagnosed with schizophrenia, he oscillated between periods as a gravedigger and a hospital porter. There were episodes of erratic behavior, trying to give away all his money, and spells in psychiatric hospitals, where he received electroconvulsive therapy.

It reappeared sporadically, first with solo recordings in the 1980s and then on a series of albums with The Splinter Group in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Relying heavily on standards and versions Cover story, and getting respectable, yet sympathetic, follow-up, they rarely disturbed the top reaches of the charts or regained their previous fire.

Rich legacy

If the headlines primarily remembered Green as a tragic figure, like other innovators of his generation who were struck down by drugs and collapse, his calm influence went much deeper. Not the first, or most famous, of the British guitar heroes, his emphasis on tone, economy, and space, however, formed the vocabulary of the rock guitar.

The likes of Jimmy Page and Gary Moore, the latter of whom recorded an album of Green’s songs, attested their impact. No less luminaire than BB King would comment: “It has the sweetest tone I’ve ever heard; he was the only one who gave me cold sweats. “