Copyright

Copyright

UCL Institute of Archeology

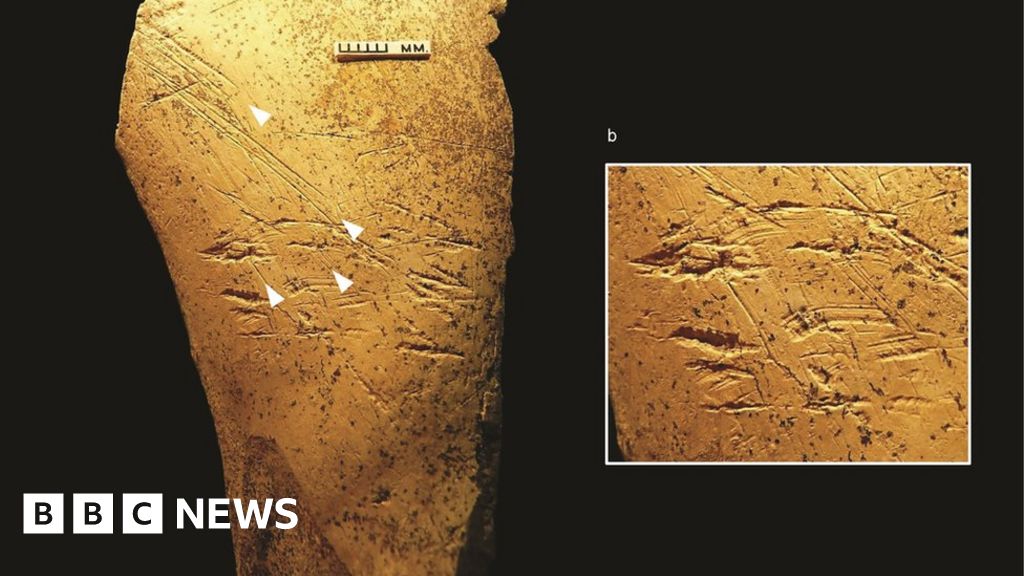

One of the oldest organic tools in the world. A bone hammer used to make the fine flint bifaces from Boxgrove. The bone shows scratch marks used to prepare the bone, such as pitting left behind from use in making flint tools

Archaeologists say they have discovered the first known bone tool in the European archaeological record.

The implementations come from the famous Boxgrove site in West Sussex, which was excavated in the 1980s and 90s.

The bone tool came from a horse that people slaughtered on the spot for its meat.

Flakes of stone in poles around the animal suggest that at least eight people made large flint knives for the job.

Researchers also found evidence that other people in the neighborhood – often younger than older members of a community – once again shed light on the social structure of our old relatives.

There is nothing like Boxgrove anywhere in Britain: during excavations, archaeologists have discovered hundreds of stone tools, along with animal bones, dating to 500,000 years ago.

They were made by the sort Homo heidelbergensis, a possible ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals.

Researchers found a leg bone that belonged to one of them – it is the oldest human bone known from Britain.

Project leader, Dr Matthew Pope, of UCL’s Institute of Archeology, said: “This was an extremely rare opportunity to explore a site quite a bit, as it was left behind by an extinct population, after collecting it around the carcass of a total to be processed dead horse at the edge of a coastal swamp.

Copyright

UCL Institute of Archeology

The horse slaughterhouse is being excavated in 1990

“Amazingly, we have been as close as possible to witnessing the minute-by-minute movement and behavior of a single seemingly tight group of early people: a community of people, young and old, working together in a cooperative and very social way. “

Half a million years ago, the area was an interim marshland over what would have been Britain’s southern coastline. There was a cliff that began to degrade, producing good rocks for cutting – the process of making stone tools. Silt from the sea had also built up here, making an area of grassland.

“Grassland means herbivores and herbivores mean food,” Dr. Pope explained.

Dr Pope admitted that it was not yet clear how the horse roamed in this landscape.

“Horses are very sociable animals and it is reasonable to assume that it was part of a herd, or attracted to the coast for fresh water, or for seaweed or salt licks. For whatever reason, this horse – isolated from the herd – ends up dying there, “Dr Pope told BBC News.

“Maybe it was chased – although we have no evidence of that – and it was sitting right next to an interim creek. The tide was pretty low, so it’s possible for people to get around. But shortly after that a high tide comes in and “begins to cover the site in fine, powdery sludge and clay. It’s so low energy that everything remains as it was when the hominins moved from the site.”

The horse provided more than just food. Bone analysis by Simon Parfitt, of the University College London (UCL) Institute of Archeology, and Dr Silvia Bello, of the London Natural History Museum, found that various bones were used as tools called re-touchers.

Copyright

UCL Institute of Archeology

A pile of stone shields was produced when an early man nodded to make a stone handgun. The impression of the person’s knee is seen in the silt.

Simon Parfitt said: “These are some of the earliest non-stone tools found in the archaeological record of human evolution. They would have been essential to the fabrication of the fine flint knives found in the wide Boxgrove landscape.”

Dr Bello added: “The finding provides evidence that early human cultures understood the properties of various organic materials and how tools could be created to improve the fabrication of other tools.

She explained that “it provides further evidence that Boxhrove’s early human population was cognitively, socially and culturally refined”.

The researchers believe that other members of the group – who could count 30 to 40 people – were nearby. They might join in the hunt to slaughter the horse carcass.

This could explain why it was so completely torn apart: the Boxgrove people even threw up their bones to get to the marrow and liquid fats.

Dr Pope said that, slaughter could not have been an activity for a handful of individuals in a hunting party, slaughter could have been a very social event for these old people.

Follow Paul on Twitter.