[ad_1]

Credit: SpaceX

SpaceX has received much praise and criticism with the creation of Starlink, a constellation that will one day provide broadband Internet access to everyone. To date, the company has launched more than 800 satellites and (as of this summer) is producing them at a rate of about 120 per month. There are even plans to have a constellation of 42,000 satellites in orbit before the decade is out.

However, there have also been some problems along the way. Aside from the usual concerns about light pollution and radio frequency interference (RFI), there is also the failure rate these satellites have experienced. Specifically, about 3% of its satellites have proven unresponsive and are no longer maneuvering in orbit, which could prove dangerous to other orbiting satellites and spacecraft.

To avoid collisions in orbit, SpaceX equips its satellites with krypton Hall-effect thrusters (ion engines) to elevate their orbit, maneuver in space, and deorbit at the end of their lives. However, according to two recent notices SpaceX sent to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) over the summer (mid-May and late June), several of its satellites have lost maneuverability since they were deployed.

Unfortunately, the company did not provide enough information to indicate which of its satellites were affected. For this reason, astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the Chandra X-ray Center presented his own analysis of the orbital behavior of satellites to suggest which satellites have failed.

The analysis was posted on McDowell’s website (Jonathan’s Space Report), where he combined SpaceX’s own data with US government sources. From this, he determined that about 3% of the satellites in the constellation have failed because they no longer respond to commands. Naturally, some level of wear is unavoidable and 3% is relatively low as failure rates advance.

But each satellite that is unable to maneuver due to problems with its communications or its propulsion system creates a collision hazard for other satellites and spacecraft. As McDowell said Business Insider:

Artist’s impression of the orbital debris problem. Credit: UC3M

“I would say their failure rate is not egregious. It’s no worse than anyone else’s failure rate. The concern is that even a normal failure rate in such a large constellation will end up with a lot of bad space junk.” .

Kessler syndrome

Kessler syndrome, named after NASA scientists Donald J. Kessler, who first proposed it in 1978, refers to the threat posed by collisions in orbit. These lead to catastrophic ruptures creating more debris that will lead to more collisions and ruptures, and so on. When failure rates and SpaceX’s long-term plans for a “mega-constellation” are taken into account, this syndrome naturally rears its ugly head.

Not long ago, SpaceX obtained permission from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to deploy around 12,000 Starlink satellites in orbits ranging from 328 km to 580 km (200 to 360 miles). However, more recent filings with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) show that the company hopes to create a mega-constellation of up to 42,000 satellites.

In this case, a 3% failure rate equals 360 and 1,260 (respectively) 250 kg (550 pound) satellites that will die out over time. As of February 2020, according to ESA’s Space Debris Office (SDO), there are currently 5,500 satellites in orbit of Earth, of which around 2,300 are still operational. That means (using naked math) that a full Starlink mega-constellation would increase the number of satellites not operating in orbit by 11% to 40%.

The debris and collision problem seems even more threatening when you consider the amount of debris in orbit. Beyond non-functioning satellites, the SDO also estimates that there are currently 34,000 objects in orbit measuring more than 10 cm (~ 4 inches) in diameter, 900,000 objects between 1 cm and 10 cm (0.4 to 4 inches). and 128 million objects. between 1 mm to 1 cm.

Mitigation strategies

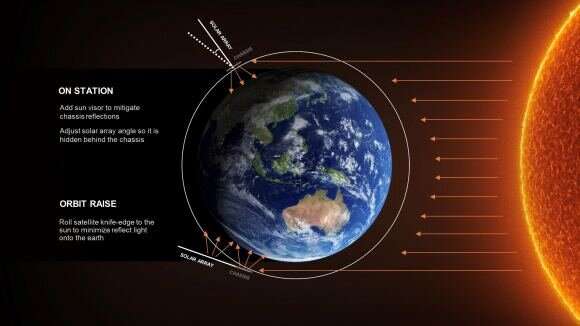

Illustration of Starlink’s orbits and their reflective qualities. Credit: SpaceX

Naturally, SpaceX has emphasized that the risk of collision is very small. In its filings with the FCC in April 2017, SpaceX addressed the possibility of collision risks by assuming “satellite failure rates resulting in the inability to perform collision avoidance procedures of 10, 5 and 1 percent.” In response, the company indicated that even a 1% risk was unlikely, given the following specifications and guidelines:

- Design the Starlink constellation to exceed NASA’s debris mitigation guidelines and an “aggressive monitoring program” to detect potential problems and deorbit affected satellites.

- An incremental deployment program over a long period of time (which they are doing by deploying a batch of 60 satellites per launch).

- An iterative design process that takes advantage of new technologies and updates, avoiding the launch of more satellites identified as problematic and exorbitant those identified as a risk.

Last but not least, SpaceX emphasized that it conducts simulations, which it corroborates with information from the USAF’s Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) and NASA’s Orbital Debris Engineering Model. From this, they claimed that, based on a 1% satellite failure rate and no corrective maneuvers, there was “about a 1% chance per decade that any failed SpaceX satellite would collide with a tracked piece of debris.”

The deployment of 60 Starlink satellites confirmed pic.twitter.com/x83OvjB4Pa

– SpaceX (@SpaceX) October 6, 2020

There is also the likely scenario where Starlink satellites naturally deorbit if their propulsion systems fail and they are unable to raise their orbit or apply a corrective boost. But even with their lower orbits, compared to other telecommunications satellites, this process will still take one to five years. At the end of the day, there are no guarantees, just vigilance and preparation.

Meanwhile, Musk announced earlier this month that with the latest batch of its satellites launched into orbit, Starlink plans to launch a beta test of its internet service. “Once these satellites reach their target position, we will be able to roll out a fairly broad public beta in the northern United States and hopefully southern Canada. Other countries will follow as soon as we receive regulatory approval,” he tweeted.

SpaceX seeks many more satellites for the space-based Internet network

Provided by Universe Today

Citation: Approximately 3% of Starlink satellites have failed so far (2020, Oct 26) Retrieved Oct 26, 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-10-starlink-satellites.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

[ad_2]