This week Ellen visited DeGeneres – with success? who can still say? – to turn the page on a bad chapter in the book of her career, one that began last month with a few BuzzFeed pieces accusing a toxic work environment on the set of her daytime dance-and-present daytime “The Ellen DeGeneres Show,” including sexual harassment and racist remarks from executives. (DeGeneres herself was accused only of allowing the incident, and that she was strange – not wanting to be seen or talked about and sokssawat.) Two producers and a lead writer have been released, a reportedly tearful DeGeneres announced Monday at a video conference call to staff.

Since the story broke, the star has made several statements of appreciation and remorse, taking responsibility, promising to “do my part” and “change and grow,” and reiterate her original desire for a show that “would be a place of happiness” “No one would ever raise their voice, and everyone would be treated with respect.”

The last instance of employees speaking more and more truths to employers, than speaking truths to reporters about employers, has been full of them mainly because of the nice image of the host, and the positivity they cultivate so arrogantly. (“Be kind to each other” is her sign-off.) That a celebrity you love may not be loved feels like a betrayal, an insult added to hurt. Some commentators swear that DeGeneres’ awfulness has been an open secret for centuries; it’s not one I’ve ever heard. But I love her sitcom.

In the old, golden days of the Hollywood studio system, battalions of publicity agents worked to control a public image of a star, to make it at once glamorous and ordinary, exciting, yet untreating, with a heavy lid on even the intimacy of any deviation from “the norm.” Involuntarily, the practice of selling public figures ran too well to be true, the company went on to expose them as too human – gossip columnists and scandal-mongers like Confidential made this their flesh – and this tension persists to this day.

YouTube swarms with videos meant to tell us that famous people are not who they want us to think they are. Celebrities who do not like is a genre of its own – mostly the same little pool of suspects, clinging to not always substantial evidence. DeGeneres gets great videos for herself, many posting just this year when Ellen disfavor Fever mounted: “Top 10 Times Celebs Clapped Back at Ellen.” “Top 10 most awkward Ellen moments,” “Top 10 times Ellen DeGeneres has been exposed,” “Ellen DeGeneres is a Hollywood PSYCHO.” The audience strikes a tone, mostly unconvincing, between shock and worry, with a bit of snoring on top. (In the middle of it all came the news – I can not say it was reliable, but it was about – that “Late Late Show” host James Corden was trying to take over the slot “Ellen”, which came to a many comments that he is also not very nice.)

Steve Carell in “The Morning Show.”

(Hilary B. Gayle / Apple)

As for the moments when it is revealed that DeGeneres ‘exposed’ her true nature’s behavior, viewers of the show did not leave the host about being a little weird with Dakota Johnson about not being invited to her birthday party, when they try – a decade ago, but pulled out in the last round of bad press – to force Mariah Carey to announce her pregnancy by trying to drink her Champagne on the air. None of the reports I have read or reviewed have mentioned that Carey has been back to the show since.

The idea that business display can not only be for it is a concept that is often put by the case itself, in backstage comedies, dramas and memoirs. “All the honesty in Hollywood you could fill in the navel of a meat,” remarked cabaret artist Fred Allen famously, “and still have room to hide eight chores and an agent’s heart,” that’s a funny line, a terrible thought and easily suspected is true, in part because we have heard that story for years.

When the sector looks at itself, it is often questionable. Whether the setting is the stage, a film studio or a TV network, the characters are familiar to us: media producers, tyrannical directors, impossible stars, bitter and cynical writers who continue to write with cynical bitterness from their experiences. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote 17 short stories about hack screenwriter Pat Hobby, even though he himself tried to make screenwriting. To SJ Perelman, who co-wrote two Marx Brothers films and “Around the World in 80 Days”, “Hollywood was” a sad industrial city ruled by hoodlums of enormous wealth, the ethical sense of a pack of shawls, and taste so degraded that it touched everything it touched. “

‘The Bad and the Beautiful’, ‘Barton Fink’, ‘Swimming With Sharks’ and ‘The Player’ have all been targeted at Hollywood; ‘Network’ took a scalp to television news. Elia Kazan’s 1957 film “A Face in the Crowd” – with a pre-Mayberry Andy Griffith as a vagabond who becomes an influential national TV personality, his folksy charm masking complete disgust for his audience – is often cited as a metaphor for the Trump era. Griffith’s character is eventually brought down by a hot microphone because he dismisses them as “morons”, “slobs” and “training seals. I throw them a dead fish and they’ll flap their flippers.”

Television has also taken its business as a topic. Around the turn of the century, Darren Star’s ‘Grosse Pointe’ took over an evil from the production of his own ‘Beverly Hills, 90210’, and Fox’s sour ‘Action’, with Jay Mohr as studio head recovering from a catastrophic flop and Illeana Douglas as the child-star-turned-prostitute he makes his head of production.

Long before both, but at this moment still very resonant, the highly regarded, short-lived “Buffalo Bill”, a resolutely hard-hitting sitcom from 1983-84, with Dabney Coleman as the popular host of a local talk show, seemed terribly offscreen as he is lovely on. In one episode, Geena Davis, as a production assistant, cheerfully describes herself to an interviewer, in words that could have been spoken yesterday, in a less chirpy tone, somewhere in this city: ‘Bill can be raw and hateful. … He does not want to be as small and prejudiced as he is, he just never really learned to like people. On the other hand, he is very kind to me, so there is hope. And the last time he’s never tried to get me in bed with him. … this is all very therapeutic for me. ”

That would play out differently today, on television and in the world. TV hosts Matt Lauer, Charlie Rose and Tavis Smiley, the latter just ordered PBS to pay $ 2.6 million in damages, all lost jobs and status over sexual harassment. Lauer seems to be superficially the inspiration for the box office of Steve Carell’s boxed breakfast on Apple TV +’s The Morning Show, which is currently nominated for an Emmys clutch. The series was inspired by Brian Stelter’s book “Top of the Morning: In the Cutthroat World of Morning TV,” and it is indeed full of scheme and double dealing as characters strive to keep their job or move into someone else, before a principle stand is finally taken. Working in TV, says the series, can break your heart when you value values, but it is not above hope.

Garry Shandling, right, as Larry Sanders on HBO’s “The Larry Sanders Show,” with Jeffrey Tambor as Hank Kingsley.

(Darryl Estrine / HBO)

No series captures this duality better than Garry Shandling’s “The Larry Sanders Show,” from back in the 20th century, a comedy set on a talk show late at night. We understand on a formal level that Larry lives in two worlds: on stage, with guests, where he is in control (recorded on video), and everywhere else (recorded on film), where he is not. Yet the character is too conflicting – he literally turns away from confrontation – and too necessary to be an active tyrant. Shades of “The Ellen DeGeneres Show,” it is his producer, Artie (Rip Torn), who maintains the perimeter (and fascinates him a little, deferentially). Most every character on the show lives at least a little bit in fear.

Authenticity, and the lack thereof, was a concern of Shandling’s; he told me in 2010 when the full series was released on home video that “Sanders” was thought of as a way to “look at myself internally, which meant I had to take a show and watch internally. And what better show for that” to participate in a talk show, which pretends to be a normal conversation, half to recognize what people are seeing and half to pretend that the host and the guest have a certain intimacy, which really revolves around inserting product. ”

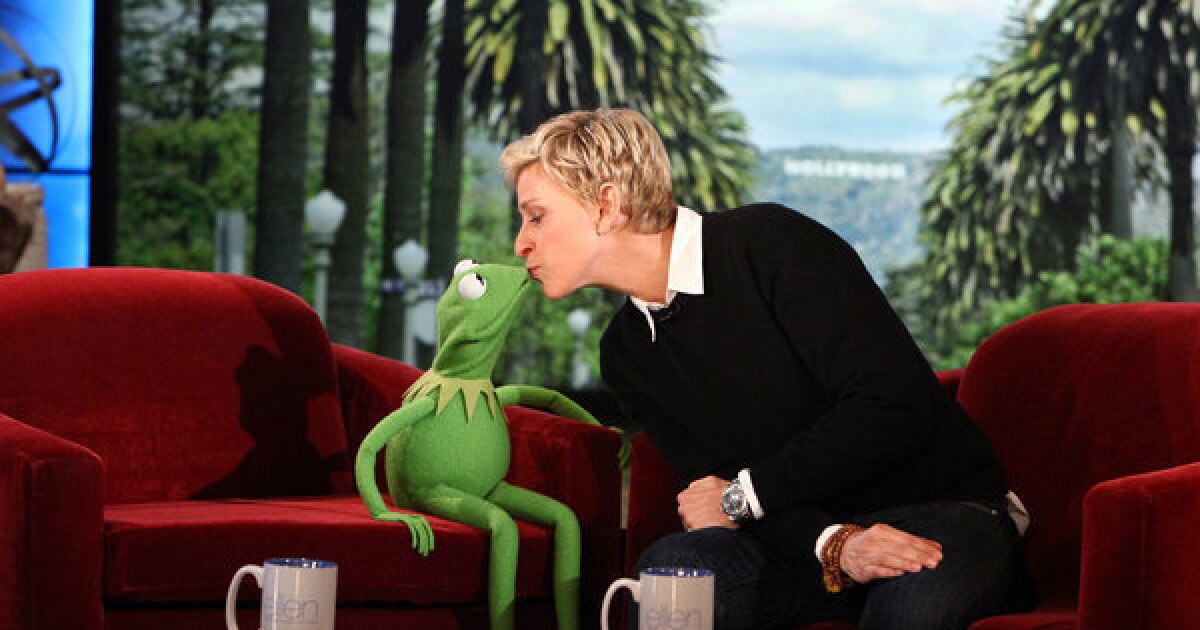

Guest stars, appearing as themselves, play against their public image, sometimes in a negative way. DeGeneres was on that performance, playing a version of herself; Interestingly, in a pre-echo of DeGeneres’ pressure on Carey to reveal her pregnancy, she finds herself pressured by Larry to announce on camera whether she will be appearing on television. (In life she had it already.) ‘Let’s just be real,’ Larry says to Ellen during a commercial break, after a frustrating first segment, and when they return, she reveals how they slept the night before. .