The sad reality of end-stage lung disease is that there are simply far more patients than donor lungs available. This is not only due to the low number of donors, which would be a sufficient problem, but many donor lungs are significantly damaged, rendering them unusable.

However, by using a new experimental technique, the function of a damaged lung has been restored by sharing its circulatory system with that of a living pig. This takes advantage of the body’s self-healing mechanisms to overcome the capabilities of current donor lung restoration techniques.

“It is the provision of intrinsic biological repair mechanisms for long enough periods of time that allowed us to recover severely damaged lungs that otherwise could not be saved,” say lead researchers, surgeon Ahmed Hozain, and biomedical engineer John O ‘Neill of Columbia University. .

The underlying principle is similar to an existing donor lung restoration technique called ex vivo pulmonary perfusion (EVLP), which involves placing a lung in a sterile dome connected to a ventilator, pump, and filters.

The temperature of the lung is maintained at the temperature of the human body, and a bloodless solution containing oxygen, nutrients, and protein circulates through it. That circulation, when fluid is pumped through the organ, is the perfusion part.

EVLP has helped save lives by keeping donor lungs stable and even slightly repairing them. But the time interval offered by the technique is somewhat limited: it can only be carried out for a maximum of eight hours, which is not a long time for the biological repair functions to come into action.

It’s that precious time that the research team has bought with their pigs, and years of research.

In 2017, O’Neill led the development of the xenogeneic (cross-species) cross-circulation platform. Last year, two of the researchers, biomedical engineer Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic from Columbia University and surgeon Matthew Bacchetta of the Vanderbilt Lung Institute, led a study in which they restored damaged pigs’ lungs by attaching them to other pigs.

Earlier this year, the team extended the platform’s operating time to four days.

Now, researchers have revealed that they have successfully used the same technique to repair five damaged human lungs by connecting them to pigs, including a severely injured lung that was unable to regain function using EVLP.

“We were able to recover a donated lung that was not recovered at the clinic ex vivo pulmonary perfusion system, which is the current standard of care, “said Vunjak-Novakovic.” This was the most rigorous validation of our cross circulation platform to date, showing great promise for its clinical utility. “

In the study, the team obtained six lungs from donors after being rejected for the transplant. The five lungs in the experiment were joined by a jugular cannula to anesthetized pigs that had been immunosuppressed, to prevent the pig’s immune system from attacking the lungs. The sixth control lung was attached to a pig that was not immunosuppressed.

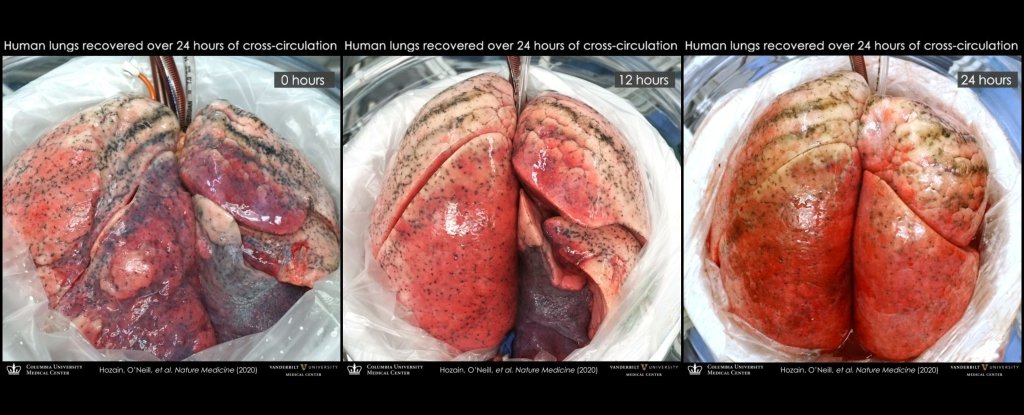

All lungs underwent 24 hours of xenogeneic cross circulation, while the researchers carefully monitored the physiological and biochemical parameters of the organs.

The control lung soon decomposed. He began to develop additional fluid, the circulation was broken, while the inflammatory and immune markers increased, blood clots formed and respiratory function decreased, all of which is consistent with hyperacute rejection.

The contrast with the experimental lungs could not have been more noticeable. Although all had previously demonstrated injury, the lungs showed a significant improvement in cell viability, tissue quality, inflammatory response, and respiratory function.

The change in the lung that had failed EVLP, in particular, underwent an astonishing change. He had spent a total of 22.5 hours on ice and received 5 hours of EVLP. After this, the right lung was accepted for transplantation, but the left lung was simply too damaged. I had persistent swelling and fluid buildup. Multiple transplant centers had rejected it.

However, after 24 hours sharing blood with a pig, the damaged lung began to show signs of repair; not a full recovery, but much more than had been thought possible. This suggests, the researchers said, that its cross-circulation platform could be used in conjunction with EVLP to help restore the lungs that EVLP cannot save on its own.

However, it is not yet ready for clinical use. For one thing, pigs could share other things besides their blood. Like disease, for example.

Because of this, any clinical use of the technique would require medical grade animals, which would not be cheap, but is nonetheless being investigated for use in xenotransplantation, in which the organs of pigs can be transplanted into recipients. humans. (This is currently being tested on baboons.)

The other option is that human receptors themselves could become the foundation of the cross-circulation platform, attaching themselves to the lungs that they will receive themselves, and perhaps even some other type of organ one day.

“Modifications to the xenogeneic cross circulation circuit could allow for the investigation and recovery of other human organs, including livers, hearts, kidneys, and extremities,” the researchers wrote in their article.

“Ultimately, we envision that xenogeneic cross circulation could be used as a translational research platform to augment transplant research and as a biomedical technology to help address organ shortages by enabling organ recovery from previously unknown donors. they could save. “

The research has been published in Natural medicine.

.