The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking) Katie Mack Scribner (2020)

Scientists know how the world will end. The sun will run on fuel and enter its red-giant phase. The last burst of glory will expand and displace the nearest planets, leaving Earth a burnt, lifeless rock. Our planet has about five billion years left.

With this grim image, theoretical astrophysicist Katie Mack begins her book at the end of the Universe – a much more uncertain perspective. Cosmologists generally look backwards, because all the evidence they can examine with telescopes is far away and is about things that happened a long time ago. Using the motions of stars and galaxies to predict possible futures involves more speculation.

In Mack’s hands, this speculation makes for a fascinating story. Humans are, she writes, “a species that arises between an awareness of our ultimate unintentionality and an ability to reach far beyond our everyday lives, to the void, to solve the most fundamental mysteries of the cosmos”. She is a talented communicator of complex physics, and the passion and curiosity about astronomy that has made her a popular speaker and presence on Twitter is evident here. (Like some nerdy jokes and a less compelling code about new physical research tangential to the central theme.)

Mack starts at the beginning, with the Big Bang. What followed was inflation – a period of rapid expansion. Then dark matter structures were formed and the building blocks of stars, planets, life, and galaxies were assembled. At present, dark energy, thought to deepen the Universe, somehow serves the gravitational forces to sustain expansion.

The fate of the Universe depends on whether that expansion will continue, accelerate or reverse.

The Big Crunch

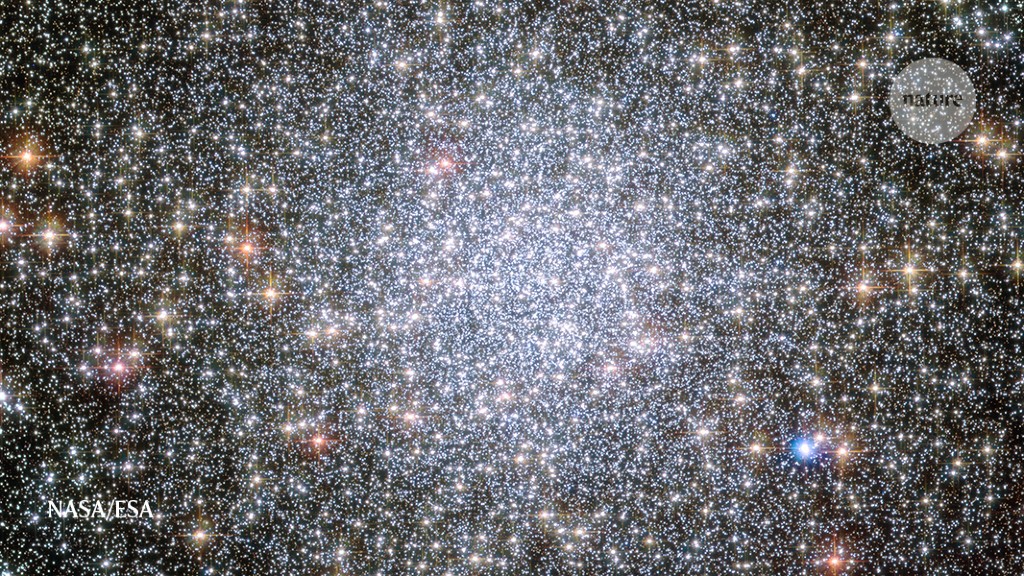

Astrophysicists have long considered the most likely denial to be a reversal of the Big Bang – the Big Crunch. Outside our cosmic neighborhood, every galaxy zooms away from us; a clear sign of expansion. If the Universe contains enough material, including dark matter, the combined gravitational attraction of all will gradually stop this expansion and precipitate the final column. Over time, galaxies, then individual stars, will collide more frequently and kill all life on nearby planets. In the last moments, when densities and temperatures die in a contracting inferno, all that is left will disappear at one point.

But dark energy could mean another end awaits. The early years of the evolution of the Universe were determined by how much matter it had; in the past few billion years, dark energy has begun to dominate, pushing the universe outward. Current data from the Planck Telescope of the European Space Agency and other sources have been consistent with this expansion forever.

Named The Heat Death of Big Freeze, this apocalypse will be “slow and painful,” Mack writes. In thermodynamic terms, she explains, the Universe will approach a state of minimum temperature and maximum entropy. As everything grows longer and further apart, the material of dead stars will disperse so that new stars cannot form, and the galaxies of which they are a part will gradually stop growing. It is like a pollution of all astrophysical activity, because the fuel for growth and reproduction becomes as diffuse as useless. It is an end “marked by increasing isolation, unforgettable decay, and an eons-long fade into darkness.”

The third death Mack discusses is the Big Rip. This is in store as dark energy accelerates the expansion even more than is now expected. Like the Universe balloons, gravitational forces can ultimately not hold galactic clusters together. Stars will drift away from each other, and solar systems like ours will not have the power to stay together. The remaining stars and planets will explode. Eventually the last atoms will ripen apart.

The latest measurements point to a Heat Death, but a Big Crunch or Big Rip are within their uncertainties.

The definitive scenario that Mack describes is very unlikely: vacuum decay. A small bubble of ‘true vacuum’ could form, due to instability in the field associated with the Higgs boson. That might happen if, say, a black hole evaporates in just the wrong way. Such a bubble would expand with the speed of light, destroying everything, until it cancels the universe. Vacuum decay might even have started somewhere. We will not see it coming.

Not to worry, though. If Mack guesses, however it seems, the end will probably not be near for at least 200 billion years.