(Bloomberg) – Crude oil is the most important product in the world, but it is worthless without a refinery that turns it into the products that people actually use: gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and petrochemicals for plastics. And the world’s refining industry today suffers like never before.

“Refining margins are absolutely catastrophic,” Patrick Pouyanne, head of Europe’s largest oil refining group, Total SA, told investors last month, echoing a widely held opinion among executives, traders and analysts.

What happens to the oil refining industry right now will have repercussions for the rest of the energy industry. Billionaire plants employ thousands of people and a wave of closings and bankruptcies is looming.

“We believe we are entering an ‘era of consolidation’ for the refining industry,” said Nikhil Bhandari, refining analyst at Goldman Sachs Inc. The industry’s top names, which collectively processed more than $ 2 trillion in oil a year Past, they are giants like Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc. There are also Asian giants like Sinopec of China and Indian Oil Corp., as well as great independents like Marathon Petroleum Corp. and Valero Energy Corp. with their ubiquitous fuel stations.

The problem for refiners is that what is killing them is the medicine that is saving the oil industry in general.

When the President of the United States, Donald Trump, designed record cuts in oil production between Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the rest of the OPEC + alliance in April, he may have saved the American shale industry in Texas, Oklahoma, and Dakota from the North but tightened the refineries.

The economy of a refinery is, ultimately, simple: it thrives on the difference in price between crude oil and fuels such as gasoline, obtaining a profit that is known in the industry as a margin of rupture.

The cuts Trump negotiated raised crude prices, with benchmark Brent crude rising from $ 16 to $ 42 a barrel in the space of a few months. But with demand still in crisis, the prices of gasoline and other refined products have not recovered as strongly, hurting refineries.

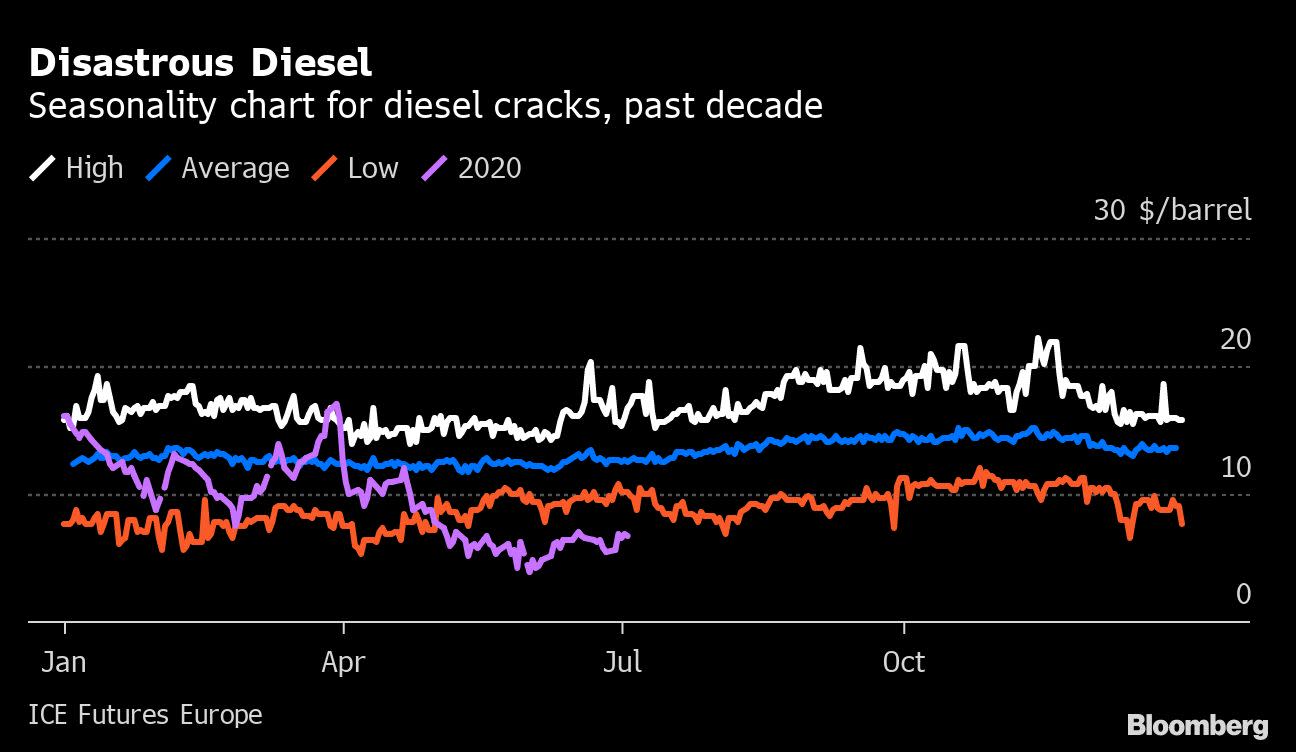

The industry’s most rudimentary measure of refining earnings, known as a 3-2-1 crack differential (three barrels of crude oil is supposed to produce two of gasoline and one of diesel-like fuels), has plummeted to its level. lowest for year time since 2010. Summer is normally a good period for refineries because demand increases with consumers hitting the road for their vacations. This time, however, some plants are losing money when they process a barrel of crude.

Worst fear

Just a few weeks ago, prospects seemed to be improving for the world’s largest oil consumers. Demand in China had almost returned to pre-virus levels and consumption in the United States was gradually recovering. Now, a second wave of infections has led Beijing to lock up hundreds of thousands of residents. Covid-19 cases are also on the rise in Latin America and elsewhere.

Now that demand in the US shows signs of turning south as coronavirus cases worsen in major gasoline-consuming regions such as Texas, Florida and California, margins are at risk of deteriorating in the United States. , which represents almost two out of every ten barrels of refined oil worldwide.

“The worst fear for refineries is a resurgence of the virus and another series of blockades around the world that would again significantly impact demand,” said Andy Lipow, president of Lipow Oil Associates in Houston.

Another problem is that, where it has been recovering, demand recovery has been uneven from one refined product to the next, creating significant headaches for executives who need to select the best crudes to buy and the right fuels to produce. Gasoline and diesel consumption has risen again, in some cases to 90% of its normal level, but jet fuel remains almost as depressed as at the lowest point of coronavirus blockades, operating between 10% and 20% of normal in some European countries. .

Refineries had solved the problem by combining much of their jet fuel production into, indeed, diesel. But that, in turn, is creating a new challenge: too many middle distillates like diesel and heating fuel.

“Right now, gasoline demand is barely keeping some plants alive,” said Stephen Wolfe, head of crude oil at consulting firm Energy Aspects Ltd. “And with airplane production in exchange for diesel and gasoline production, that puts even more pressure on product supply. ” added.

In the U.S. refining belt, processing rates are continually changing in response to possible fluctuations in demand. In April, during the height of the US closings, Valero Energy Corp.’s McKee, Texas refinery cut rates to around 70%. It then increased processing to about 79% in anticipation of the Memorial Day holiday, before finding a new low of 62% in mid-June, according to people familiar with the situation.

Ultimately, if refineries don’t make money, they buy less crude, which could limit the recovery in oil prices in recent months for Brent and other benchmarks. Still, stocks in Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the rest of the OPEC + group suggest that refineries will continue to push for longer, with oil prices outpacing the recovery in fuel prices.

The immediate problem is compounded by a longer-term trend: The industry has probably overdeveloped in recent decades, and older plants in places like Europe and the US can’t compete with the new ones popping up in China and in other parts of the world.

“Refinery margins over the next five years will be worse than the average over the past five years, and particularly bad in Europe,” said Spencer Welch, vice president of oil markets and downstream consulting at IHS Markit. “We already thought refining was at a difficult time, even more so now.”

Catalyst for change

The weakness means that the industry’s collective earnings will drop to just $ 40 billion this year, down from $ 130 billion in 2018, according to an estimate by industry consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd. of 550 refineries worldwide. .

That could be a catalyst for change. According to Goldman Sachs analysts, the demand for the virus has not yet caused delays in several mega-refining projects, most of which are in China and the Middle East, which will start operating from 2021 to 2024. This will cause rates of global utilization are 3% lower during this period than in 2019. Plants are more likely to close in developed countries because most of the demand, and the new refining capacity, is in developing countries, they said.

Many of the refineries being built in the Middle East and China will also receive government backing, a fact that only makes life more challenging for plants in Europe and the US.

The industry is already moving to resolve excess capacity: Oil trader Gunvor Group Ltd. has said it could cut its refinery in Antwerp, and US refining group HollyFrontier Corp. announced in June that it was changing its Cheyenne plant. of processing crude oil in a renewable diesel facility.

For now, however, there is a more mundane reality to contend with: the market. OPEC and its allies can restrict the supply of crude by squeezing the refineries, but they cannot make end users consume fuel.

For more items like this, visit us at bloomberg.com

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted source of business news.

© 2020 Bloomberg LP