A few miles west of Fort Collins in Fort Laura, Cameron Peak fire engulfs 200,000 acres and is still growing. It has now become the largest wildlife in Colorado history.

More surprisingly, Cameron Peak Fire is the second wildfire in Colorado’s history in 2020. The Pine Gulch Agni near Grand Junction held that title for a while, but for just 7 weeks, it burned 139,000 acres in late summer.

Seeing this in a vacuum, you might think of it as just a coincidence. But for more unprecedented fire evidence than Zoom, you only need to look at two states in California. California has six of the 7 largest wildfires in history All burned out in 2020, And The largest, August complex fire, Became the state’s first gigafire – meaning it burned over 1 million acres, burning more plantation area than Rhode Island state.

Rear by Lutland Fire Rescue Authority

This year Mother Nature has provided us Smoke-gun evidence To prove what climate scientists have been warning for decades. Accidental effect of Climate change has come.

In a letter to the editor of the journal Global Change Biology, two of the world’s leading experts on wildfires concluded that “[r]The accord-setting atmosphere enabled an extraordinary 2020 fire season in the western United States. ”

“Our 2020 wildfire season is showing us that climate change is here and now in Colorado. Wimming is setting the stage for a lot of burning in an extended fire season,” said Dr. A.S. Says Jennifer Balch. At the University of Colorado Boulder.

According to Balch, the average burned area in Colorado in the 2010s saw a threefold increase in burn area compared to the previous three decades of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. “We’re seeing fall fire events in Colorado, which are related to fast, downslop winds. But it’s very rare to see so many events begin in mid-October.”

Maybe it’s rare, but by Monday 10 significant fires are burning across the state. The eastern boundary of Cameron Peak Fire is only 5 miles from Fort Collins and Loveland.

Google Maps

The most important thing in Boulder County is the two new burning and forced evacuations. The Woodwood Fire – the largest fire ever in Boulder County – and the fire on the left have both demonstrated extreme fire behavior, shocking even seasonal climate scientists.

“Even as a scientist studying extreme weather and forest fires in a warm environment, I was shocked by how fast I was. # CalwoodFire The foothills of the Colorado Front Range are buzzing, “UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain wrote on Twitter, posting a video of a vortex of smoke.

Examining all the evidence, it is clear why this fall is extraordinarily flammable. It is a compounding issue of stratified short-term natural climate variability on top of fundamental changes in long-term climate change from global warming.

“This year has been shocking”

While you can’t completely separate short-term weather from long-term weather trends, as they are interrelated, the most recent weather conditions in a region are a big factor in how extreme the fire season is.

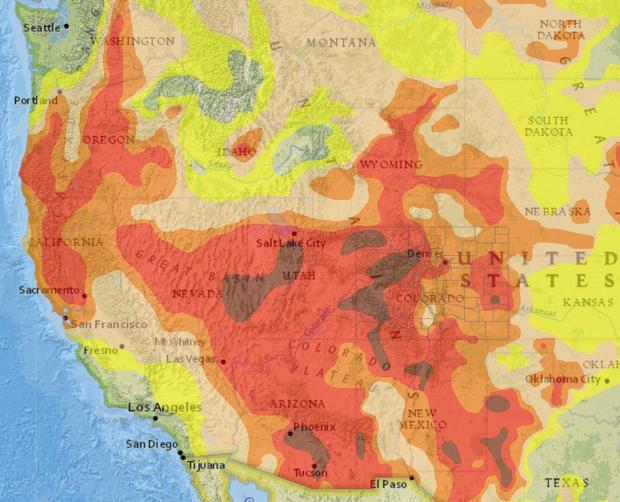

According to Colorado Climate Center At Colorado State University, for the first time since 2013, all Colorados are experiencing a drought. This is not a dry spell – 97% of this state is in the “exceptional,” “extreme,” or “severe” drought category. And it’s not just Colorado; The bones of the southwestern part are dry.

Drought

Brad Udale, a senior water and meteorological research scientist at the Colorado Water Institute at Colorado State University, said 2020 was beginning to be promising.

“This year has been shocking because we had a decent winter one and on April 1 we had 100% snowpack.” But things quickly became frustrating. “With 100% snooping, you’d expect a good weak year. Instead, we finished 52% better than usual.”

The water that escapes from the ice cover and the speed at which it melts are important as it determines the availability of water for the soil and vegetation in the summer.

Udal says weak runoff due to very hot and dry spring and summer is the result of increasing evaporation. There have been a lot of significant heat waves in the west over the past few months, two of which were historic historical proportions. Excess heat energy evaporates the spring snow cover, and the lack of new moisture provides nothing to buffer the damage.

In the southwestern states, the rainfall from June to August was the lowest since 1895 and the highest since 1895, according to the NOAA. So far in Colorado, this year is the eighth hottest and the second driest on record. Denver has experienced more 90-degree days than any other year in its history.

“We haven’t had any humidity in the last 3 months, which is very unusual. The Arizona monsoon often has humidity in Colorado but this year it was a full bust,” Udale said.

The map below illustrates how the demand for an atmosphere for evaporation is “off the charts”. The more the atmosphere draws moisture from the soil, the drier and more flammable the trees, grasses and bushes become.

Udal says that most of the droughts of the 20th century were due to lack of rainfall, today’s droughts are mainly due to evaporation due to hot weather. But drought is commonly referred to as a short-term issue, and what is happening in Colorado is not temporary. He prefers the term aridity, as climate change, the burning of fossil fuels, and the overhead of blankets of carbon emissions from heat are systematically drying up the landscape.

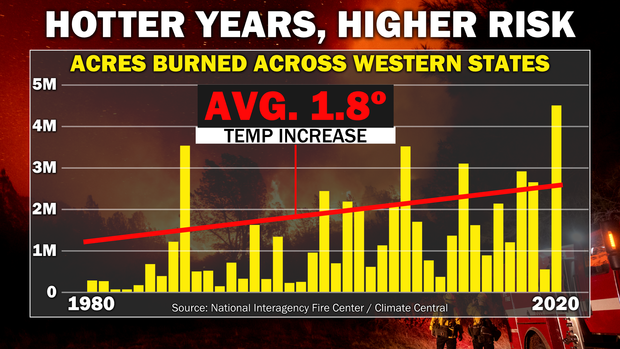

To be sure, climate is not the only cause of an explosion in a burned area. Increased ignition of firefighters in recent decades will play a role due to increased fuel buildup as well as increased human activity in forested areas. But experts say a significant increase cannot be explained without long-term temperature and drying.

Climate change and the “big forest fire recipe”

If you look at the last century, parts of Colorado are warming faster than anywhere else in the nation. According to NOAA data and analysis by the Washington Post, western and northern Colorado has been warming at about 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit since 1895, at twice the world’s average temperature.

A study published in September found that combined heat waves and the frequency of droughts – which occur at the time of uniformity – are more effective – especially in the western U.S. In, for example, the type of hot-dry phenomenon that would have been expected once every 25 years in 1950, now occurs five to 10 times every 25 years.

“Episodes of extreme dryness and heat are the remedy for large forest fires,” said Mojtaba Sadeg, senior author of the study. “This extremity is intensifying and expanding on unprecedented space scales, which could cause wildfires to burn on the current U.S. West Coast.”

Colorado State Climate Specialist Russ Rush Schumacher agrees, telling Colorado Public Radio that this corresponds to weather forecasts, “What we’re seeing here is an indication of the fact that when hot, dry years come, they’re hot.” “I think this kind of summer frequency will increase where we get in this hot, dry situation.”

Udal agrees, and warns that we will get used to what we call “new unusual.” “The weather system has a really good memory and it’s hard to break the cycle of heat and dryness,” he said.

Since 2000, famine in the western states has become such a monument that scientists are using the term “scientists”.Megador“To describe it, this spring climate Tuna climate scientists have released a groundbreaking study, saying that this is the beginning of the second worst drought in the last 1,500 years, with” human-climate change contributing greatly. ” “

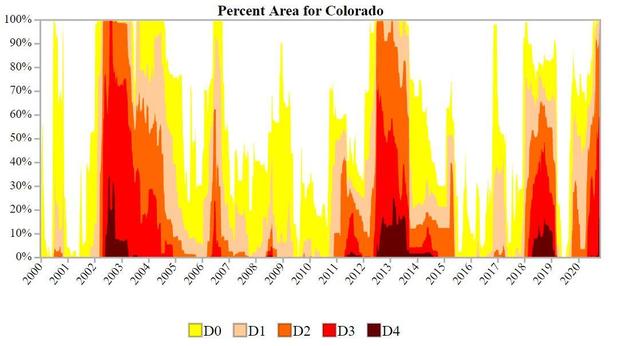

The following graph from Drought.gov shows that drought has become a regular and potentially permanent part of Colorado’s climate over the past 20 years. Darker shades mean dryer conditions, in which D2 represents “severe drought, D3 represents“ severe drought ”and D4 represents“ exceptional drought ”.

Drought

The effects on the Colorado environment are obvious. Water from the Colorado Snowpack has declined by 30% since the 1930s. As a result, the flow of water into the Colorado River has been significantly reduced. In a 2018 study, Udal and co-authors found that a 50% reduction in river flow was due to temperature.

And this more arid climate is heavily affected by huge wildfires and long fire seasons. In fact, the wildfire season in the West is now two to three months longer than in the 1970s. And since 1984, changes in the human-climate climate have led to a doubling of the area burned in the western states, an increase of about 50% thanks to an increase in fuel dryness.

CBS News

A 2015 study on wildfires in the Colorado Front Range Corridor found that more people living on the edge of forests – and climate change – were both to blame for the changing fire trends, but climate change was a “strong influence.”

Balach says your inability to square the needs of our modern society with a rapidly changing environment is a dangerous proposition.

“Ignoring the link between warming and wildfires only endangers lives and homes,” he said. “Over the past 24 years, 1 million homes in the U.S. have been engulfed in wildfires. About 59 million homes in the wildlife-urban interface are within a kilometer of a fire.”

The unprecedented wildfires of the last few years have certainly shown how sensitive we are to the environment, which does not follow the rules taken by our parents and grandparents. And given the warming and drying estimates in the coming decades, scientists say the rules will only keep changing, making “the 2020 record unlikely to stand for long.”

.