In particular, the viral genome was sequenced using traces found in vaccination kits of the time, and put together by scientists “like a puzzle” as described by lead author Ana Duggan.

Smallpox vaccine trials date back to 1796, when British physician Edward Jenner observed that milkmaids exposed to a milder relative of smallpox, called “cowpox,” were protected against the more serious disease.

Between Jenner’s early trials and the spread of modern, standardized vaccination practices that led the World Health Organization to declare smallpox eradicated in 1980, doctors practiced person-to-person vaccination. That involved collecting infectious materials from an individual and applying them to a wound in a healthy person to cause an immune reaction.

Traces of this type of material were found in the vaccination kits examined in the study.

“The molecules we collected from these objects were highly degraded, not virions or intact genomes, but small, small pieces of DNA that had broken down over time,” Duggan explained.

CDC conducted tests to ensure there was no risk of exposure to the live virus, but the authors’ greatest concern was to protect the kits from contamination with modern DNA.

“All the lab work was completed inside an old DNA clean room where we wear full Tyvek suits, masks, and gloves to protect the samples,” Duggan told CNN.

To retrieve relevant traces from the kits, Duggan and his team soaked or rinsed the objects in a buffer solution to release molecules from the surfaces.

“When those molecules were released in solution, we were able to purify the DNA fragments and sequence them so that we could begin to unite the genomes to identify the viruses that were used for vaccination,” Duggan explained.

Kits spent decades in the wrong drawer

Vaccination kits were found by chance in a drawer in the phlebotomy section of the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

“The exterior of the kits looks exactly like a bloodshed kit, so it’s understandable that they might have ended up there decades ago. I’m glad we found them and put us on the path to scientific discovery and innovation. “Anna Dhody, the director of the Mütter Research Institute and co-author of the study, told CNN.

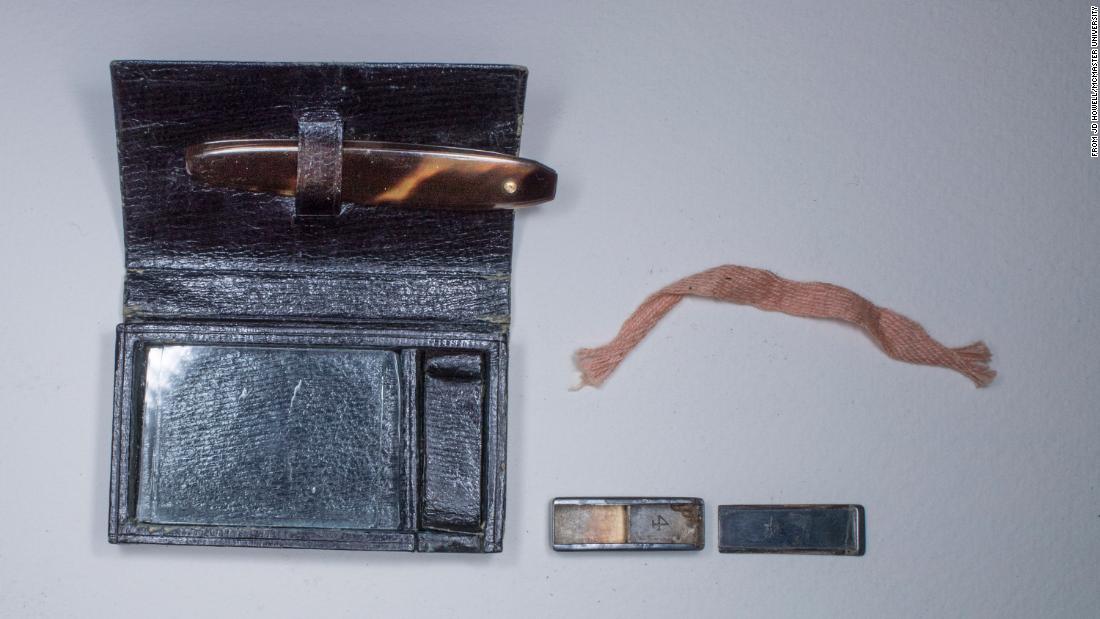

Opening the kits revealed the presence not only of lancets that would have been used for bleeding, but also tin boxes and glass slides used to collect samples such as crusts and lymph from blisters from people who had been deliberately infected.

A whole new area of research threatened by coronavirus

Scientists recovered traces of DNA from the scabs found in the kits, and other relevant molecules from inorganic elements such as tools and cans, through a non-destructive sampling process, which Dhody said could pave the way for museums in all the world. world to research their own collections in new ways.

“There could be treatments, there could be cures,” Dhody told CNN.

“It is up to us as a society to recognize the value of these collections in terms of their life-saving medical potential,” he added, noting how the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic is jeopardizing the survival of many medical museums.

“For every medical museum that closes, that information may very well be gone forever. That’s scary, because we haven’t even begun to scratch the surface of what they could tell us,” Dhody said.

‘Many possible solutions to eradicate a virus’

The study also reveals how the virus strains used by Civil War-era physicians were only distantly related to those used in commercial vaccines in the 1970s and 1980s, when smallpox was effectively eradicated.

“Our Civil War era vaccines and 20th century vaccines were all vaccinia viruses, yet (ours) are not identical to any of those later commercial vaccines,” Duggan told CNN.

“Based not only on the usefulness of multiple different strains of vaccinia but also on the ability to use the vaccinia virus as a vaccine source (actually probably any other orthopox virus other than variola) to successfully infer immunity against variola virus, we discussed that there are many possible solutions to eradicate a virus, “added Duggan.

Duggan explained that this conclusion has encouraging implications for the current coronavirus vaccine research process.

“Drug and vaccine development is very different today than it was in the 19th century, but it is evidence that exploring multiple vaccine sources and strategies has potential.”

Hendrik Poinar, director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Center and co-author of the study, said why it is useful to study a variety of vaccine strains.

The power of vaccination.

While the world is eagerly awaiting development in the field of coronavirus vaccines, Duggan said it is important to celebrate the achievements and successes of previous vaccination efforts.

“I think the biggest parallel between the smallpox vaccine and Covid-19 is the combined global effort for a greater public good in eradicating this virus,” Duggan told CNN.

Smallpox eradication, according to Duggan, “started with doctors who recognized they had a procedure that worked, they didn’t necessarily understand why it worked, but they knew it saved lives.”

Even before crucial discoveries about viruses and even the formulation of the germ theory, smallpox doctors worked collaboratively and shared best practice information on a global scale.

“As we search for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the work of Edward Jenner and subsequent physicians worldwide to eradicate smallpox should inspire the value and potential of vaccine research and a reminder that effective vaccines can be quite evolutionary far from the etiologic agent they are designed to protect against, “Duggan told CNN.

.