[ad_1]

It all started with the sound. The phone chime screeched in manager Steve O’Rourke’s office. On the other end of the line, the soft but firm voice of a small, hairless young man rang out. He was a filmmaker, he said, his name was Adrien Maben and he wanted to make a movie with Pink Floyd. For a few minutes, as an investor offering his imported knickknacks, he spoke to him of “a marriage of art and music.” They remained to be seen. They talked cups of coffee a couple of times. “They would think about it,” the agent promised.

Before long, the enthusiastic boy had his confirmation. He could film with them during the boreal autumn, in October of that 1971. There were a few months left. Meanwhile, the quartet went on tour and in the meantime spent full afternoons developing their long suites of strange sounds.

For his part, Maben began to think about the possible scenery. Almost by chance he found it. During the summer he went to visit Italy. There he came across the ruins of Pompeii, an ancient Roman city that for centuries slept under a tomb of ashes thrown by Vesuvius in AD 79. As he continued on his way he realized that he had lost his passport and had to return to the ancient amphitheater there. , with the night closed.

Before him was the stage he needed. “It was the silence, it was the night, it was creepy, this is where the Pink Floyd should be,” he told Prog magazine.

Maben had been struck by Pink Floyd for the mysterious quality of her proposal. For this reason, in some way, the moldy stone walls, the petrified subjects with the grimace of terror and the old paintings provided an overwhelming environment for music that at the time sounded ethereal, expansive and powerful.

“I thought it would be very interesting to show how they made their noises, their electronic sounds and put them all together,” says the filmmaker. His music seemed fantastic and different compared to other groups. You had all the little whispers, and the noises, and the squeals. It was a different world, and that different world was absolutely fascinating. “

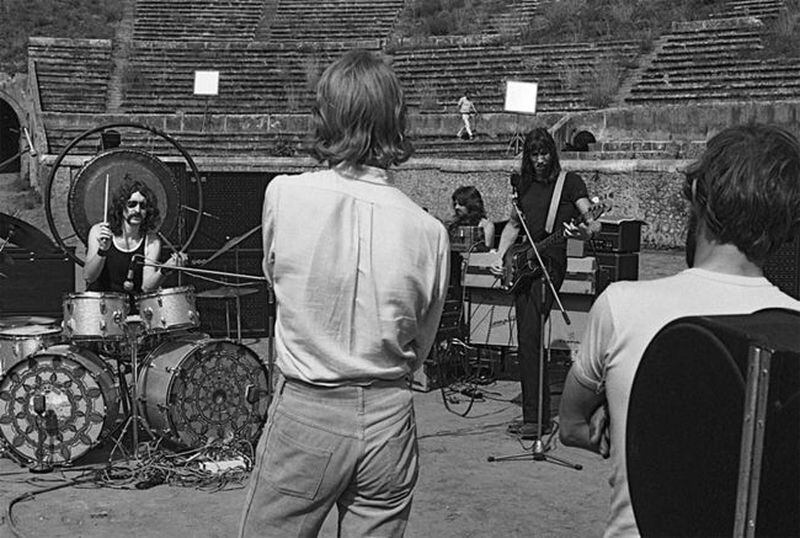

Therefore, it would be a concert without an audience. If in concert movies back then, like the one recorded by the Woodstock festival or the documentary Gimme Shelter From the Rolling Stones, the ecstatic audience before their idols was as important as the artists, this would be different. It was about the sound.

“It must have been an anti-Woodstock,” Maben explains in his interview with the aforementioned magazine. Above all, there should be the notion of silence, and images [de Pompeya] they would speak for themselves with the music. It was something that had to stand on its own: Pink Floyd and the emptiness of the theater. Maybe, just maybe, it was like they were playing for the ghosts of the dead. ”

Immediately came the difficult. It was evident that at a site of archaeological ruins – it was named a World Heritage Site in 1997 – a rock band would not be easily admitted. Maben must have found someone to intercede for him. He found it in the Professor of Ancient History at the University of Naples, Ugo Carputi. This was the one who spoke to Haroun Tazieff, the Soprintendenza in charge of the site.

“They were afraid of a large crowd climbing monuments, removing stones,” Maben explains. I told him that I wanted to do a concert where the only thing we will see is Floyd himself, a little of the technicians, zero spectators. That is what finally assured him. The Soprintendenza did not know who Pink Floyd was, but fortunately Carputi did: she had listened to his music and liked it. ”

They got the place closed for six days.

The film was intended for television. Thanks to the efforts of the director, who works in the French industry, financing was obtained from the Télévision Belge Francophone, the German company Bayerischer Rundfunk and the French Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française Office. But in view of the magnificent scenery, producer Reiner Moritz suggested shooting on three cameras with high-quality 35mm film. This was key in the subsequent success of the film.

For the team, Maben managed to sign seasoned professionals. The Hungarian-Italian Gábor Pogány and the Belgian Willy Kurant, who had worked with Serge Gainsbourg and Orson Welles, participated.

For their part, the Pink Floyd only made one condition: they wanted to be filmed playing live, no playback. Furthermore, they demanded that the sound should be studio quality. If it was a concert, then seriously. “That meant recording on-site, so the recorder came from Paris because we couldn’t get one in Rome,” says Maben. In charge of the recording was the engineer Charles Rauchet, who installed all the equipment in one corner.

What was Pink Floyd in 1971? a lot and nothing at the same time. In those days, the group was in the middle of a search and sound exploration phase. “They had their hands on too many dishes: the symphonism of ‘Sysyphus’ and ‘Atom Heart Mother’, the pastoral work of ‘Granchester Meadows’ or ‘If’, the psychedelia a little behind the scenes of ‘Summer’ 68 ‘, rock n’ hard roll of ‘Nile Song’ or ‘Ibiza Bar’ ”, details the Argentinean Norberto Cambiasso in the book Selling England for a pound. A social history of British progressive rock (Gourmet Musical, 2014).

But if something in particular had the group, it was a powerful live show. As guitarist David Gilmour once said, the problem was that they were very good at improvising live, but they found it difficult to translate that efficiency into the compact grooves of an album. According to Cambiasso, in those days they needed to find a long-term composition that confirmed their greatness and allowed them, once and for all, to define themselves, to take a more established sonic model to work with.

Like sound chemists, the group worked on the basis of constant trial and error. They also chose to save everything, however small, in a process of recycling their own musical fragments. They then carried a gigantic file that they used to call, with their customary irony, “the rubbish library.” This allowed them to develop, little by little, a work system – after previously failing with others.

“Unlike his contemporaries, Floyd worked with minimal units,” Cambiasso explains, “a basic chord structure, a piano fragment, the strumming of guitar strings, a mere sound that they liked or an interesting effect.”

Pompeii will welcome Pink Floyd in the final part of that musical quest that will allow him to take a leap forward in his creative (and why not, commercial) career. Above all, from a piece that, on the walls of the ancient Roman amphitheater, will be shown in all its dimensions.

The Italian sun shone high on the hills in that October of ’71. Pink Floyd arrived after a brief European tour in which they participated in the Mountreux Festival. Next to them, a gang of Avis trucks, which followed them from London, with all their enormous load of equipment. In its shots, the film will immortalize the speakers and speaker towers with the stencil inscription “Pink Floyd. London ”

As soon as the musicians wanted to start testing all their devices, they realized that the electrical outlet was not working. “I had been to the Soprintendenza two weeks before and he assured me that electricity would not be a problem, since it worked throughout the site. When we tried it and the Floyds came, it didn’t work. “They had to make a connection from the ruins site to modern Pompeii, with a single cable, to connect everything.

But between the arrival of the group and the matter of electricity they burned three days. They only had three others left to film everything. And it was still difficult. One morning, Maben led the group to the sulphurous mud banks of Boscoreale, on the slopes of Vesuvius, to take the insert shots where they are seen walking in the vicinity. But it took hours. They ran into the annual procession of Our Lady of the Rosary. The bus, with the technicians and the band, must have lagged with holy patience, after the faithful.

It was then that manager Steve O’Rourke asked Maben to include in the film two of the new songs that the band created for their album. Meedle (1971). “Steve came up and said, ‘This is what we really want to do.’ I told him I couldn’t wait for him to work on this for the next morning because I had planned everything else, “recalls the director. He must have stayed up all night planning the shots, listening to the songs over and over again.

One of these was “Echoes”. A 23-minute composition developed from different motifs, which occupied an entire face of the album. It had come almost by chance. “A single note on the piano passed through a Leslie cabinet, amplified by a rotary speaker, which, thanks to its variable velocity, created a Doppler effect,” Cambiasso explains. Then a guitar figure responds, until Gilmour and keyboardist Richard Wright start singing together. “Overhead the albatross / Hangs motionless upon the air”.

It is the piece that he presented to an already mature group. For Cambiasso, it is a turning point in his career. “The ‘languid’ chords, of evolutions always postponed, that take an endless time to develop; the environmental plateaus, brimming with sound effects and ominous atmospheres; the organ’s ambivalent drones, as if suspended in their own space; the sonic textures and the continuous additions of colorations ”.

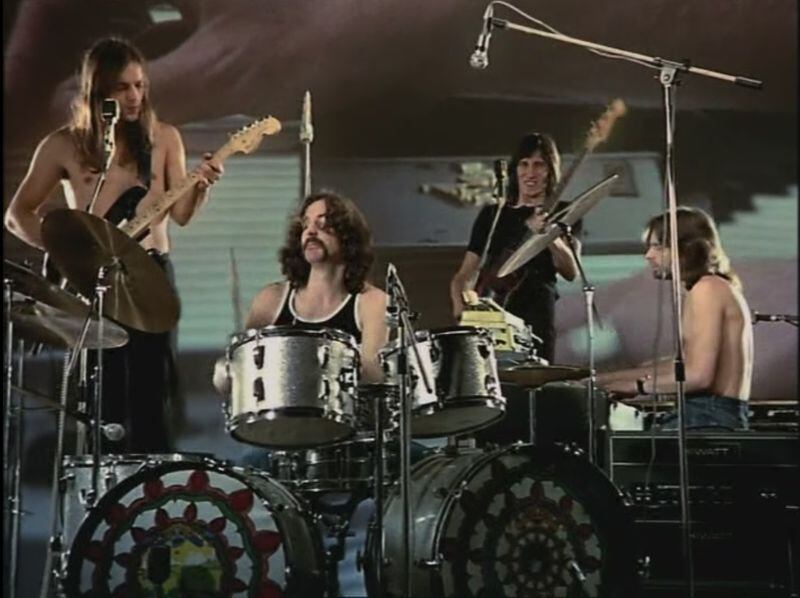

The sequence in which the group plays this song begins with the far-off chop, in which they are seen as tiny in the center of the amphitheater, surrounded by their teams; like a sort of sonic gladiator. From there the direction hooks the close up to the faces of Gilmour and Wright, and the sets of shots, in the part of the guitar solo -laden with delay- in which the fills that Nick Mason strikes in his enormous Ludwig kit of six pieces, which included Supraphonic drum, a classic of rock drummers in those years.

Finally, only “One of These Days” and “A Saucerful of Secrets” (far superior to their studio version) were recorded on location. The latter includes another memorable sequence: the hits to the gong launched by Roger Waters. The slim, tall bassist takes the mallet and whips it against the huge cymbal as his companions create dissonant layers of sound, seasoned with different figures filled with echo and delay.

The closing of this passage is the section entitled “Celestial Voices”, guided by Wright’s organ, in which the group develops a mystical improvisation, which progresses in a dramatic crescendo with Gilmour’s vocalizations and Mason’s furious blows to Zildjian saucers. It seemed as if those Englishmen, descendants of Saxons, were calling to the grave of those ancient men and women, patricians, commoners, turned into a statue of ash as a price for eternity.

Due to the characteristics of the amphitheater, the group’s compositions sounded particularly majestic. “Peter Watts – Pink Floyd’s road manager – said the sound had a kind of echo, not a dry sound like in a studio,” Maben recalls. He suggested that the Romans who built the amphitheater thought not only about the structure but also about the acoustic qualities. ”

“We were filming in Pompeii in the early autumn, but it was still quite hot and you could be shirtless,” Mason recalls in his text. Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Chronicle Books, 2005) -. It was hard work, with no free nights to sample the local cuisine and wine, but the atmosphere was very nice and everyone was very busy with their work. ”

As the director was still missing material, the group filmed a session at Boulogne Studios near Paris in December 1971. They took advantage of the day to add some additional recordings to the audio captured in Pompeii. It was there, behind a giant screen that showed Transflex projections, where they recorded pieces such as “Careful with that ax, Eugene”, and the oriental “Set the controls for the heart of the sun”, which somehow fit with the aesthetics of the film. They also added a fuck, which seems out of place with the rest of the dense recordings, “Mademoiselle Nobs”: a theme in which the group makes Maben’s friend-a beautiful Afghan Hound-dog sing while Waters and Gilmour play a generic blues and diligent Rick Wright struggles to direct the microphone towards the hound.

Live at Pompeii, premiered at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1972. But some pieces were still missing. Maben asked the group if he could record them working on their next album. “Okay. Come to London next week with minimal equipment and please don’t interfere with our work,” said Roger Waters. In this way, in October of that year, the director attended the final sessions of The Dark Side of the Moon in the Abbey Road studio, for a couple of days until he was “invited” to leave. Thanks to this material – for example, the session in which Gilmour recorded guitar phrases for “Brain Damage” – the film was extended to 80 minutes, and was the version that became more popular. This was launched in the summer of 1974.

Critics received the film with mixed opinions, although the most negative ones tended to prevail. “In fact, it’s pretty boring, unimaginative and silly and doesn’t do Pink Floyd’s vision justice,” commented the Billboard review.

In version Director’s Cut (92 minutes), some scenes recorded in the Paris sessions were added, such as the one in which Waters answers some questions to Maben. “Are you happy with the movie?”, The director throws at him. The bass player, after puffing, boastful, some smoke rings, replies “What do you mean happy?”

“Making the actual recording at the amphitheater in Pompeii was great, but we had to make it a more interesting document than what was happening,” recalls Gilmour, who also recorded a concert at the venue in 2017. Adrian wanted to make an art movie with art and music in a special place. So the idea changed a little bit and it seemed to him and us that more things were needed. “

But the main contribution of Maben’s work was finding the musical documentary par excellence. One that effectively recreates how a band creates its sound, is linked with time and captures a unique moment; in this case, it is the moment before they become a bombastic and bombastic stadium machine, which will lead them towards their period of glory, but also towards their self-destruction thanks to the inclement government of Waters with an iron fist.

“I liked it,” Waters said years later, quoted by Prog, “it’s just a great home movie.”

[ad_2]