[ad_1]

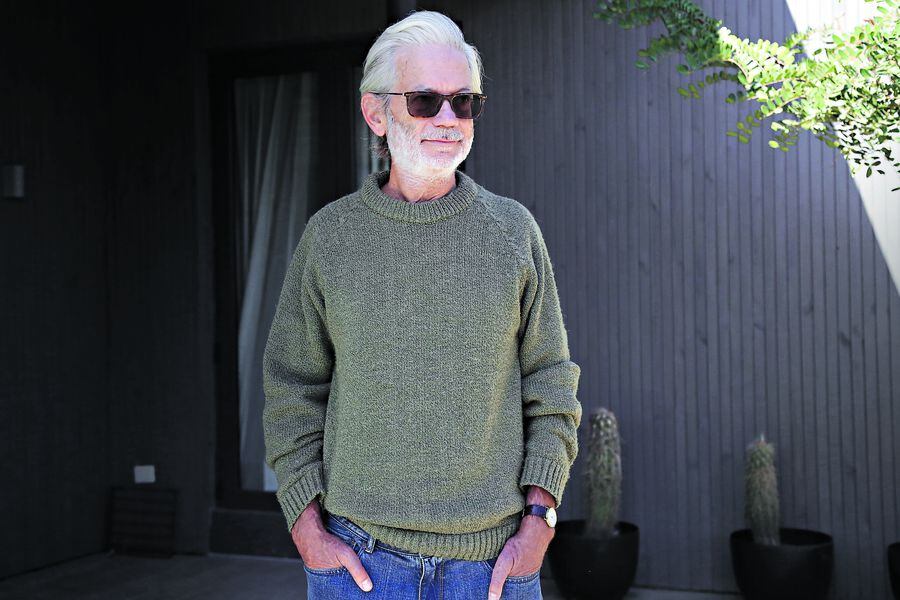

Juan Andrés Fontaine has been living his own “new normal” since he left the government, at the end of last October, days after the social outbreak. Along with four other secretaries of state, he left the cabinet at the request of President Piñera, after a little more than four months in charge of the Ministry of Economy – for the second time, after in the first government of the President he occupied the same portfolio and also left in advance- and after having been in charge of Public Works at the beginning of the administration. Almost from then until now, he practically moved to live in his house on the central coast, from where the double crisis that the country has faced has followed, first because of the events that followed 18-W and today because of the pandemic. of the coronavirus. His plan is to reinstate Fontaine Consultores, his private consulting office, but at the moment that is subject to developments. He accepts this, the first interview -by mail and telephone- since he left the Executive, to give his gaze on the recession that is looming over Chile and how to fight it to limit its effects. He is less pessimistic than other economists and highlights the lessons of the crisis of 82-83, among them, “that in the darkest hour – and today we are approaching it – everything looks very black, but economies can change surprisingly quickly ” What he does warn is that in these anomalous circumstances, numerical projections are of no greater value. “If they are always random, today they are reckless,” he says. He affirms that due to the quarantines and closings, “in these months it will not even be possible to carry out credible and compatible surveys to measure GDP, unemployment or the CPI: we will be blind. But beyond this, the nature of this phenomenon is so different that the instruments, the models, the equations used to forecast simply do not work ”.

What is your vision of the severity of the economic crisis that is causing the coronavirus globally?

-We are facing an unprecedented economic situation, but much less serious than the Great Depression or other great crises, including ours in ’82. There have been many pests and their human cost has been terrible. But never before has there been one in which the almost entire world economy paralyzed, something like the planet falling ill in bed. However, the nature of this phenomenon is very different from other major crises. In them, the contraction of demand and production, the destruction of jobs, the collapse of companies and banks were due to involuntary mistakes made by economic agents or by governments. Keynes speaks of the “disobedient psychology of businessmen” as the cause of the boom and bust cycles. Friedman attributes them to central bank failures. And for this reason, traditional fiscal and monetary policy instruments are designed to correct or neutralize these errors and to revive the economy. On the other hand, with the coronavirus we are headed for a recession that in a certain sense is deliberate, as a result of the social distancing or confinement measures adopted, either by the authorities to stop the spread of the virus, or voluntarily by people to protect themselves from contagion. . But if health restrictions are effective in stopping the pandemic in two to three months – and so far, with the information available, there is no reason to hope that they are not – they can be progressively lifted and the economy can recover quickly. It is true that there are many epidemiological doubts – the virus is new – and economic – we do not know how battered the economy will be – but the degree of uncertainty prevailing over the future recovery of the economy and the consequent financial damage that the affected families and companies will suffer they will be much less than those that occurred in the Great Depression or in our debt crisis.

And in Chile, how big will the coup be? The Central Bank (BC) and the Treasury see a drop in GDP of around 2% in 2020, while the IMF speaks of -4.5%.

-I broadly share the IMF’s reasoning: it is most likely that in Chile and the world there will be a contraction of unprecedented proportions in the second quarter and then a recovery that, if the correct policies are applied – a crucial requirement – will possibly have also unprecedented speed. The length of the bad period will depend, among other factors, on the success in controlling the pandemic, on the developing pharmacological innovations, on the financial damage suffered by families and companies, and on the ability of economic policies to promote the post-pandemic reactivation. . Things can always go worse, but so far, everything I see in the world about the advance in the control of the pandemic or the resurgence of the Chinese economy after its reopening makes me think that the most likely economic scenario is an abrupt one fall and a strong recovery.

But now it is being said that the virus can remain present for up to two years. Doesn’t that go against the V-shaped rebound you see?

– Pessimistic scenarios are always possible to guess. But I see clear progress in containing the pandemic worldwide and I am confident that pharmaceutical innovation will succeed with the right remedies or vaccines. There are already four vaccines starting the first human tests. Meanwhile, hygiene and social distancing measures should continue to help, for example, to limit outbreaks, and the health systems of Chile and the world will have gained time to prepare better. So, I insist, I share the scenario of strong recovery of the IMF for the world economy from the end of the year. In our case, with a high dollar, low interest rates and cheap oil, I hope that we can also recover with great speed, but the return of political violence, which despite the pandemic has not completely disappeared, and of constitutional uncertainty, can be a serious impediment.

How to deal with the dilemma between return to activity and maintenance of isolation measures? How is Chile doing it?

So far, the figures show that Chile has been doing well. But it is early: the virus has just begun to reach the most populous communes, quarantines tire, winter is coming. Minister Mañalich’s strategy seems correct to me: partial closings and progressive reopening, according to technical criteria and objective antecedents. It is a strategy that has the flexibility to adapt, always prioritizing the care of human life.

The Minister of Finance said that life should be watched, but also the means for life. Do you share it? Is it time to return from companies and businesses?

-It must be evaluated by epidemiologists. I am not an expert in the field. Fortunately, we are in good hands: the Minister of Health is.

How has Ignacio Briones done it at the Hacienda? For many he was the person indicated post 18-0 for his ability to dialogue and reach out to the population. Is it also against the Covid-19?

-Simple and direct style, with flexibility, but without populism, it has done very well.

Are the measures taken so far by the economic authorities in Chile sufficient and on time?

At first it seemed to me that, both in Chile and in other countries, the approach was wrong. There was talk of fiscal and monetary stimulus measures – such as lowering rates, which in current conditions at most serves as a salute to the flag – to revive activity, when sanitary measures pointed in the opposite direction: staying home and, therefore, paralyzing the economy. But then the focus has been correct: the role of the State is today to go, and with a sense of urgency, to the rescue and help of the victims. Specifically, establish monetary aid for families who have lost their sources of income and credit support to companies to face their cash needs in the emergency.

And is that sense of urgency being met?

-As never before today a sense of urgency is necessary and I have doubts if the design of the mechanisms is as broad and agile as required. For example, the suspension of employment contracts has certain restrictions. It also seems to me a mistake to demand that the state guarantee be used only for new bank loans and not to refinance the maturities that fall these days, which is the most pressing need. Nor do I think that the maximum interest rate of TPM plus 3% set by law helps, because it can leave out many SMEs. It is imperative that at this juncture the banks act with maximum speed and height of sight, but the detail of the mechanisms can be perfected to facilitate their application.

You lived through the crisis of 82 and 83 in Chile and arrived at the Central Bank on 84, from where you still dealt with its effects. What lessons from that episode should be considered now?

-Chile is incomparably stronger today and that crisis was of a depth and duration much greater than what is expected from the current one: real rates of over 30% per year, doubling of the real price of the dollar, reduction of the current account deficit, which It measures the uptake of external financing, from 14% of GDP in 81 to zero in 83, cumulative drop in those two years of 17% of GDP and 30% in domestic demand, unemployment over 25% and the banking system shattered. But, keeping the proportions, there are useful lessons.

First, a payment system crisis hurts businesses a lot and can seriously delay recovery. The usual bankruptcy and judicial collection systems cannot be relied upon to function smoothly in the face of such a massive problem. The economy could not operate well, after the pandemic, with a productive system on the brink of bankruptcy and, therefore, state aid is essential. Second, these measures always generate winners and losers, but it is a mistake that is paid dearly – as it happened then – to spend a lot of time debating who should “pay for the broken dishes” (whether the State or individuals, companies, banks or your national or foreign creditors, etc.). It is preferable to opt for general aid and automatic application formulas, even if they cost the State money. Third, interventions must be applied urgently, but designed with a long-term perspective: easy fiscal measures to dismantle, financial support that does not promote bad practices, decapitalize banks or staticize the economy. Fourth, that in the darkest hour – and we are approaching it today – everything looks very black, but economies can change surprisingly quickly. I will never forget that when in February 1985, two and a half years after the devaluation, Minister Hernán Büchi launched his plan for adjustment and recovery, the comments we received in the BC – I was director of studies – from the IMF, the The World Bank, foreign banks and renowned economists, were that a new recession would be inevitable. Six months later, no one doubted that the rebound had begun. If we handle ourselves with skill, this time also the dawn may be close.

In fiscal matters and with a deficit this year of 8% of GDP, how much space does Minister Briones have left to act?

– The fiscal turn has been extraordinary, but I am more concerned with the permanent spending commitments incurred by the outbreak, than the transitory disbursements that the pandemic forces. Do you need more? Space must be saved for a possible fiscal stimulus once the health situation allows the reopening of the activity. Uncertainty may take time to dissipate and restrain private demand. Later, it will be essential to resume strict fiscal discipline and aim for a primary fiscal structural surplus, that is, before interest, which will require disbursements of more than 1% of GDP.

Will the Employment Protection Law and the Fogape Law be enough to avoid massive bankruptcies of companies? Should the state help big companies?

-Regarding the Fogape, as I said, it seems to me well on the way, but unnecessarily restrictive. Today, the first priority is not new loans -necessary later for reactivation-, but helping companies to meet their current obligations. Regarding large companies, as there are strong and well-liquidized banks in Chile, as well as other financial intermediaries and eventual capital contributors, the solution must be negotiated between them and their creditors. As for state guarantees, I think that Corfo -as we did for the post-earthquake reconstruction of 27 / F- has a role to play, for example, in supporting not only SMEs, but the tourism sector, whose recovery is likely to take longer than the rest.

How much more can the BC do?

-The main function of the BC today is to create confidence in the liquidity provision of the economy. Rightly so, that’s what he’s been doing.

Do you agree to modify the Constitution so that the BC can buy Treasury bonds in the secondary market?

-There are two different prohibitions in Article 109 of the Constitution regarding the operations of the BC with the Treasury: one prevents it from acquiring public titles, the other prevents it from granting direct or indirect credit. The first excludes from the monetary policy arsenal a common instrument in other countries -the so-called “repos” with Treasury bonds-, as well as the term purchase of such bonds, which, very exceptionally, has been used in the USA. and Europe in the past financial crisis and lately too. Lifting this limitation may be useful in the future, but it is neither urgent nor necessary today. The BC can make monetary policy or deliver liquidity aid, either by buying bonds, for example bank, or by delivering lines of credit, either guaranteed with bank placements or simply without guarantees (as was done in the 1980s). Introducing this constitutional amendment, besides being unnecessary, is disturbing, since it confuses public opinion and alters expectations. The issue arises when there are growing needs for state financing and it is not necessary to look underwater to warn that lifting the restriction could serve for the BC to indirectly provide, through the purchase of state securities to the BancoEstado or other banks, financing to cover its large deficit .

And wouldn’t that option be valid for emergencies?

No, the constitutional provision that prevents the BC from granting direct or indirect credits to the Treasury is very healthy, and it should be interpreted as an impediment to all types of financing from the State. The reason is simple: except very marginally or occasionally, a BC is not a new source of financing and the funds that it can contribute to the Treasury, in the long run, always come from inflation (which acts as an inefficient, regressive and unregulated tax) ), or from its own debt placements in the market, which are equivalent to those that could be made directly by the Treasury. It does not seem responsible to me to open this discussion today, in the presence of very high fiscal requirements and on the brink of an unpredictable constitutional process, in which until now the BC seemed untouched. Whoever doubts the consequences of untying confidence in fiscal and monetary discipline, just look to the other side of the mountain range.

With all the bad things about this pandemic, there are those who glimpse an opportunity, and in fact the President has returned over 20% approval. How do you see the government moving forward and the country in two to three years?

-It is still too early to assess the political effects of this catastrophe. What the citizens of President Piñera and his government value most is their management capacity. A situation as serious as today makes management more valued than empathy. And, for now, the administration of the government has been agile, realistic and effective. Of course there is still bad news in health and economics. Regarding the future, the greatest risk is the return of violence, political confrontation and constitutional uncertainty. But the harshness of winter will help to land expectations, to value the country that we have built among all-despite its shortcomings-and to feel that we all sail in the same boat, so we had better row all the same way.

[ad_2]