[ad_1]

In the mid-1970s, most cases of hepatitis transmitted by blood transfusion when analyzed did not correspond to any of the viruses known up to that time. It was named with the term Hepatitis noA-noB.

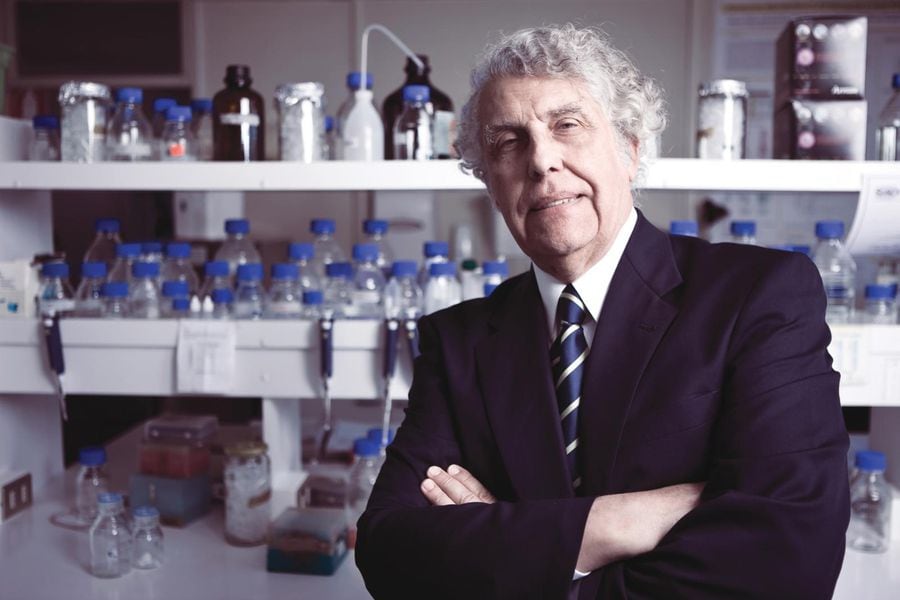

In 1981, in the United States, William Rutter and the Chilean scientist Pablo Valenzuela founded the biotech company Chiron Corporation. And one of the most ambitious projects by the new company was to identify this virus. “It was a very important project,” he acknowledges today Pablo Valenzuela Scientific Director of the Science & Life Foundation, National Award for Applied and Technological Sciences in 2002, from Berkeley, California, United States.

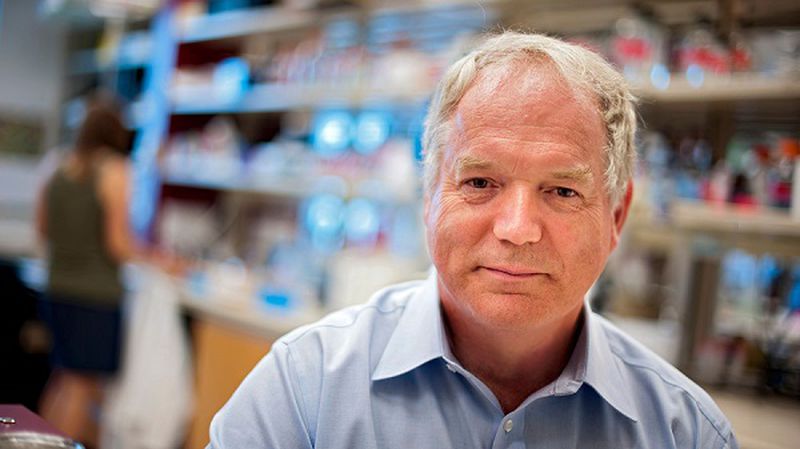

But Valenzuela, as Chiron’s vice president of research, couldn’t be directly in the lab on that job. For this task, in 1982 he hired a post-doctoral researcher who wrote to him from England that he wanted to work at Chiron. It was about British Michael Houghton, today recognized worldwide for being one of the Laureates of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

“When he arrived, I went to meet him at the airport. I took him to the laboratory and he was opposed in principle to working on a virus where more than 15 people and more than 15 years had worked and had not been discovered. What happens is that when one is after a virus there are no partial results, the virus is discovered or it is not discovered. But he had the strength to stay in the project for 6 years and in one of those we found out “Valenzuela notes about Houghton’s work.

The study of the transfusional hepatitis virus or not A not B, was a rather difficult project, acknowledges the Chilean researcher. “Almost all the academics had already failed and had been unable to find the reason for why there was blood that gave rise to a disease called transfusion hepatitis, which was the only thing that was known, “he says.

Houghton isolated the genetic sequence of the virus. He determined that it was a new RNA virus belonging to the family of flavivirus and it was called the hepatitis C virus, “For Chiron,” says Valenzuela.

Back then the National Award for Applied and Technological Sciences of the year 2002He admits he was afraid of not being recognized. “We were afraid that it would not be recognized, because in the end we were a company, we were not an academic group. They all came from the academy, but we were in a company and I was afraid that the encounter with this virus and the ability to use this virus for a number of other things would not be recognized.

Today the contribution of that work is indisputable. And the Nobel proves it. “The impact of the discovery of this virus that is called transfusion virus or hepatitis C, is that blood banks before it was discovered, were distributing and infecting people who had transfusions. After we find it, we prepare the tests to check everyone’s blood bags, and Hepatitis C infection by transfusion disappeared worldwide, that was the strongest effect”, He emphasizes.

A discovery that has facilitated the development of effective diagnostics. Blood tests and promising drug targets and to control this pathogen.

There is still no vaccine for hepatitis C. However, says Valenzuela, “another company using our data on the structure of the virus has discovered antivirals that are very effective against hepatitis C ”.

He hadn’t spoken to Houghton yet, admits Valenzuela: “Just send him congratulations on having this award. He expresses his joy and satisfaction for the Nobel: “I am proud. I am very grateful. I think it is a great thing that the importance of discovering a virus and also discovering a possible solution to the problem is finally understood. Today no one dies from hepatitis C”.