[ad_1]

Urban planning discipline was born to reduce or control the infectious diseases that plagued the population during the Industrial Revolution (19th century). The first urban planning laws were hygienic or sanitary. They regulated certain activities outside the densest population areas, included water supply and sewerage networks and plans for urban reform and renovation.

Different theories of spatial, social, and economic production organization also emerged (such as C. Fourier’s phalansteries, 1808-1837) that gave rise to new urban models. The garden city of E. Howard (1889) or the linear city of Arturo Soria (1885) are some examples that were reflected in newly created cities or areas of expansion of existing urban centers. They were looking for a harmony between the advantages of the city and the country.

In the densest fabrics of the consolidated cities, the opening of wide boulevards and avenues was a very general solution to guarantee light, radiation and ventilation as minimum living conditions (Haussman in Paris, the Gran Vía in Madrid, etc.).

Urban diseases

The analysis Delivering Healthier Communities in London in 2007, he pointed out new relationships between the city and the built environment and its residents. According to the document, urban diseases were mainly related to a sedentary lifestyle and poor air quality.

The work included a list of cardiovascular, respiratory, obesity, cold and heat stroke, accidents and mental illness. This registry of non-infectious diseases typical of large agglomerations is directly aligned with Sustainable Development Goals 3 (health and well-being) and 11 (sustainable cities).

Un

Most of the urban parameters such as population density, ratio of green areas per inhabitant, urban mobility patterns, distribution of urban green areas, structure of land uses and urban morphology can be used to alleviate, adapt and improve determining factors. environmental issues of the 21st century city.

In the UNI-Health project (EIT Health BP2019), led by the ABIO-UPM research group, we analyzed and established lines of action to improve the conditions of public spaces in the consolidated city, from a perspective of active and healthy aging of the population.

Currently, we participate in the international project URB-HealthS). Its objective is to define strategies and lines of action to promote health and establish transversal preventive measures from local corporations with the participation of the municipalities. Their results will be presented in early 2021.

One of the lessons learned to date is the need to adapt public spaces to the needs of an aging population with reduced mobility (sometimes it is a more psychological than physical issue). New spaces of intergenerational coexistence must be articulated, including the vegetation in the design.

The local scale is considered the most appropriate to articulate efficient diagnoses and formulate responses to the specific needs of each city and each neighborhood.

The Spanish Network of Healthy Cities within the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces and in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare has developed manuals, measures and held conferences and seminars on urban planning and health to publicize and promote this type of new solutions at the local and municipal level.

The city in front of COVID-19

During the first months of 2020 we have found a new panorama at the global level: the expansion of COVID-19.

Many questions have arisen regarding the model, operation and use of cities. It is questioned whether the rapid spread has had anything to do with high density and concentrated urban models, with modes of displacement, with social behaviors or with the lack of preventive measures for contagious diseases.

To analyze these factors, new research must be started, which must necessarily be multidisciplinary, multi-agent, establishing public-private and multigenerational collaborations. Only in this way can future contingencies be articulated under the social, environmental, economic, political and urban spheres, coordinated under SDG 3 (health and well-being).

Impact on older people

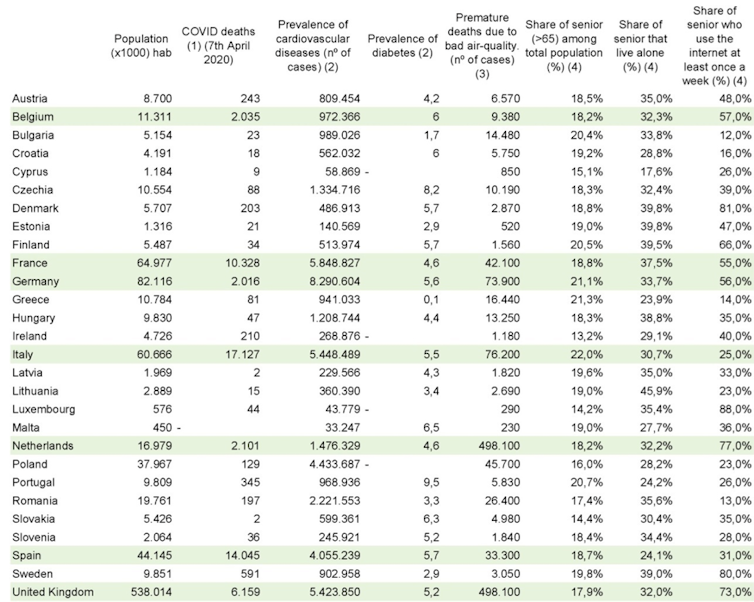

Another topic discussed is the impact that the coronavirus has on vulnerable population groups such as the elderly and those with respiratory conditions, cardiovascular problems or diabetes.

If we compare mortality data by country in Europe, a relationship can be seen between the higher prevalence figures for these conditions and premature deaths in general and the high numbers of deaths from COVID-19. A fairly high number of older people is also confirmed in countries where there have been more cases.

Own elaboration based on data from World Do Meters, European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017, European Environmental Agency and Eurostat, Author provided

The figures on the percentage of older people living alone in the different countries – Spain is the one with the lowest percentage – may partially explain the high number of deaths in Spain. In other countries, serviced housing, the cohousing o Intergenerational programs are more generalized alternatives for the senior population.

In any case, it will be necessary to review the care model and integrate it into the design of the cities. In Spain it will be necessary to question the residential models and their management, which have been denounced for years.

It is also interesting that both in Italy and Spain it seems that older people have less access to the internet. Given the need for technology to stay in touch with families, facilitate communications and use the big dataIt may be an interesting fact to keep in mind later.

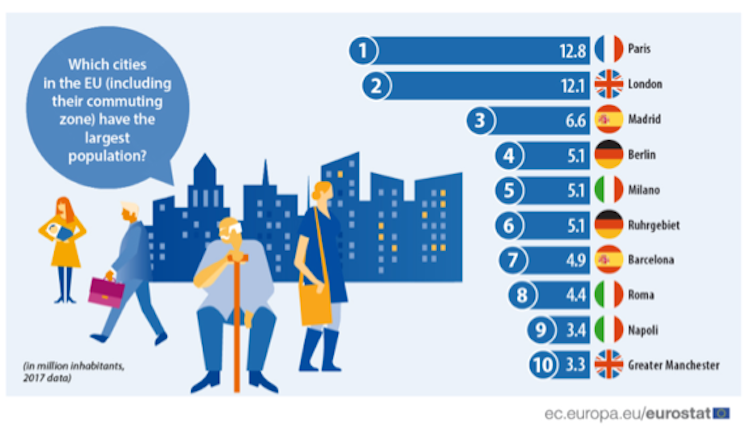

Eurostat, 2020

Density, mobility and green areas

For the present, we have focused on the five cities with the largest population in Europe (Eurostat, 2020) to observe mobility dynamics in recent weeks.

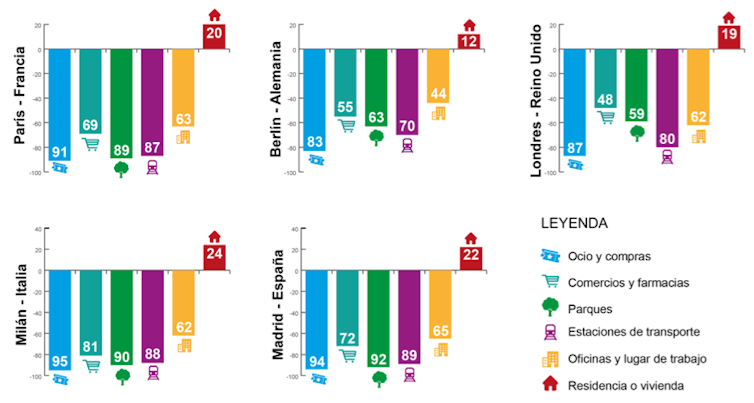

Pozo Menéndez, based on data from the Community Mobility Report (Google)

At first glance, the values with the greatest variations are mobility in parks and green spaces and to fresh produce stores and pharmacies. Here there is an important difference between London and Berlin and the other cities: Paris, Milan and Madrid.

It is evident that these dynamics are conditioned by the declaration of the state of alarm and the more or less strict restrictions of each country. However, it is worth asking about the benefits of contact with nature and the ability to remain during confinement in better physical and, above all, mental health conditions, and consumption patterns in local proximity businesses.

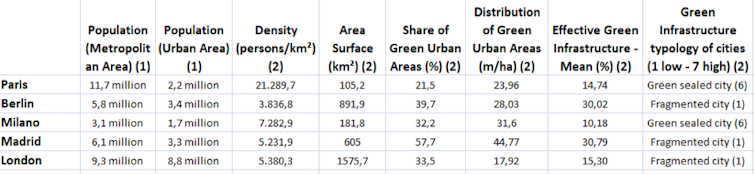

The following table collects the data corresponding to the green infrastructure of the analyzed cities:

Pozo Menéndez based on data from the World Population Review and the European Environmental Agency., Author provided

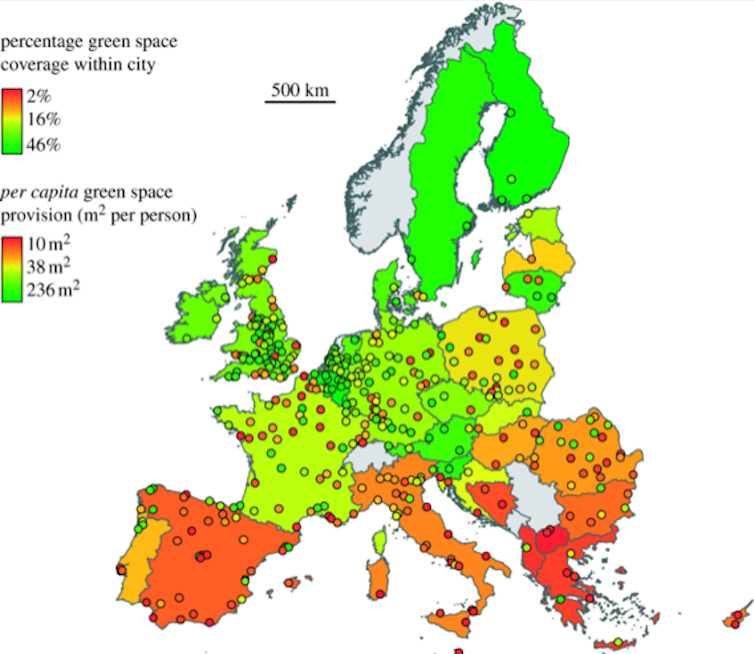

It can be seen that both Berlin, London and Madrid are classified as fragmented cities. Its green infrastructure is disconnected and there is a high degree of impervious surfaces compared to scarce green surfaces. The following map shows the percentage of green space in cities and the corresponding area of green space per inhabitant in each city:

Biol Lett. 2009 Jun 23; 5 (3): 352–355.

To the values of green infrastructure, which have an environmental focus, it would be necessary to add the health factor: the accessibility of green spaces by the population has positive effects related to stress reduction, physical activity, etc.

Madrid, for example, presents green spaces mainly outside the M30 ring. Only residents of these more peripheral areas would have access to proximity parks.

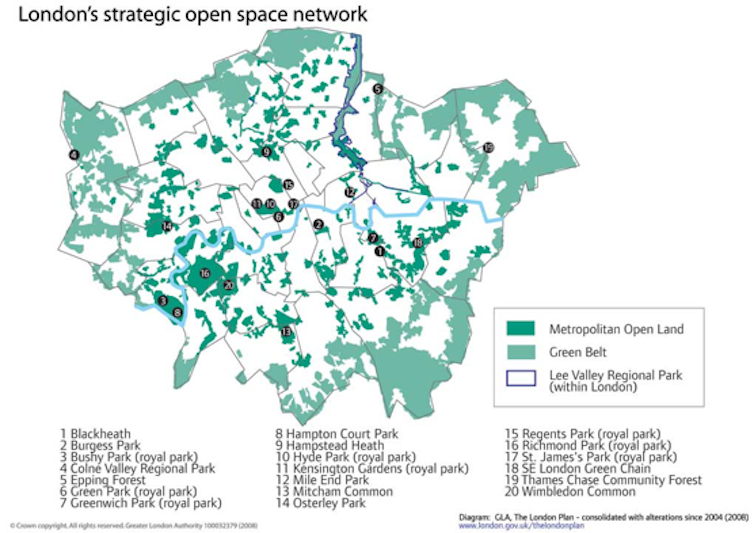

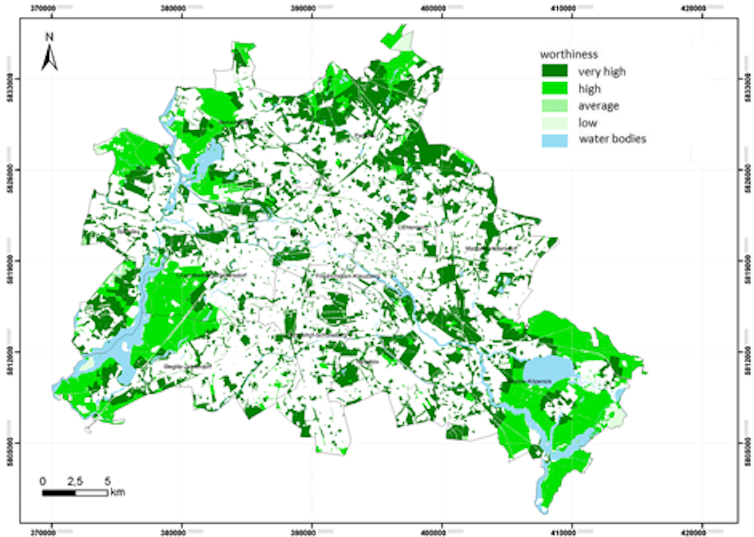

In London and Berlin it seems that people continue to maintain their physical activity in parks and green spaces. This measure coincides with the high level of development of the strategic plans for green and blue infrastructure, health promotion and mental health in these cities.

City of London

Berlin.de

The values regarding mobility at transport stations in Berlin could be due to the widespread use of other means of transport such as the bicycle. Mobility patterns related to local shops and small producers also show a smaller decrease. They are dynamics and elements that, together with the mapping of neighborhood solidarity networks, can help to understand the resilience of cities and communities to epidemics.

Need to adapt cities

It is still too early to be able to make comparisons at the urban level on the data from the COVID-19 pandemic. But it is worth asking about the resilience of cities to face these new emergency situations.

In urban planning and the environment we have been working for years on mitigating the effects of climate change and adapting city infrastructures to face possible future scenarios. Health and the prevention of non-communicable diseases is another of the great research topics to avoid premature deaths and improve people’s quality of life.

The appearance of COVID-19 has once again highlighted the need to rethink the cities and spaces where we live with the priority objective of ensuring the health and quality of life of the population.

Nor can we forget that the essence of the city is the density and complexity of activities. Salvador Rueda has already established four essential attributes for an eco-neighborhood or eco-city: density, complexity, efficiency and social cohesion.

Now we see that we do not only have to answer the question of energy efficiency (that solves the matter and energy cycles of the city). It is also necessary to guarantee the health efficiency of cities for the future.

One possible solution is to establish preventive health areas delimited around health centers specialized in infectious diseases that can articulate measures at the neighborhood level and control the health parameters of their neighbors.

These areas must be accompanied by social care in public spaces, where elements of temporary prevention can be articulated according to needs. A new responsibility for the use of public space will help us to optimally manage and manage uncontrolled propagations.